A Thanksgiving Message

Happy Thanksgiving from the OLLS!

Happy Thanksgiving from the OLLS!

This week’s article is the second in a series that summarizes the bills recommended by each of the 11 interim study committees that met this year. The Legislative Council met […]

The Legislative Council met Tuesday, November 10, 2015, to review all of the bills recommended to them by the legislative study committees that met during the 2015 interim. With the […]

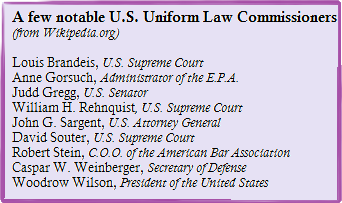

by Patti Dahlberg and Thomas Morris Editor’s Note: This is the third article in our series on the Uniform Laws Commission. The preceding articles were posted on Sept. 17 and […]

by Melanie Pawlyszyn How often have you sat in the Old Supreme Court Chambers and wondered, “Who are those people in the windows?” As it turns out, each window honors […]