Wishing you a safe and happy holiday season!

An informational and educational resource for the Colorado General Assembly by the Office of Legislative Legal Services.

by Julie Pelegrin

‘Tis the season. Children are working on their letters to Santa; legislators are working on their bills, diligently meeting with drafters, lobbyists, and stakeholders, trying to craft effective policy to address the state’s issues. Once the policy is worked out, a legislator may figure, “That’s it; all done drafting. Finally I can get that holiday baking done!” But wait – the bill drafter will be pestering legislators with one last question: “Do you want a safety clause or an act-subject-to-petition clause on your bill?”

Here’s a little background information to use in making this important decision.

When first approved in 1876, the Colorado Constitution placed the legislative power of the state solely in the hands of the elected members of the Colorado House and Senate. And that’s where it stayed for almost 35 years. But by the early twentieth century, many people had become disillusioned with government; they no longer trusted elected officials to act solely in the public interest. The progressive movement arose, and the people started demanding a role for themselves in making the laws. They wanted to put the “demo” back in democracy. At the general election held in 1910, Colorado voters adopted an amendment to the Colorado Constitution—placed on the ballot by the General Assembly—that put the power to make laws directly in the hands of the people through the twin powers of initiative and referendum.

When first approved in 1876, the Colorado Constitution placed the legislative power of the state solely in the hands of the elected members of the Colorado House and Senate. And that’s where it stayed for almost 35 years. But by the early twentieth century, many people had become disillusioned with government; they no longer trusted elected officials to act solely in the public interest. The progressive movement arose, and the people started demanding a role for themselves in making the laws. They wanted to put the “demo” back in democracy. At the general election held in 1910, Colorado voters adopted an amendment to the Colorado Constitution—placed on the ballot by the General Assembly—that put the power to make laws directly in the hands of the people through the twin powers of initiative and referendum.

Using the power of initiative, any individual may propose a change to the constitution or to statute by collecting and submitting to the Secretary of State a sufficient number of signatures on a petition. To place an initiative on the 2022 ballot, an individual must collect at least 124,632 signatures (5% of the total number of votes cast for the office of Secretary of State in the previous general election). The initiative is a positive power, empowering the people to create, change, or repeal law.

In contrast, the referendum power is a negative power, empowering the people only to rescind all or part of an act passed by the General Assembly. By collecting the same number of signatures required for an initiative and submitting those signatures to the Secretary of State, an individual may place all or part of an act on the ballot for the electorate’s approval or disapproval. But the time for rescinding an act is limited; the signatures must be filed with the Secretary of State within 90 days after the end of the legislative session in which the General Assembly passes the act.

There are two exceptions to the power of referendum. The people cannot refer an act to the ballot if: 1) The act is “necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety”; or 2) the act is an appropriation to support a state agency or institution. Deciding whether an act is an appropriation is relatively straightforward. If all it does is appropriate money, and it does not enact any actual changes to the law, it is likely an appropriation and therefore not subject to the referendum power. But who decides whether an act is necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety?

The General Assembly does by including what’s called a “safety clause” at the end of the act: “The general assembly hereby finds, determines, and declares that this act is necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety.”

The Colorado courts have held that the General Assembly alone is authorized to determine whether that declaration is appropriately included in an act. While legislators may certainly debate whether to use a safety clause in a bill, once the General Assembly decides that question, the decision stands; the court will not overturn it. In Van Kleeck v. Ramer in 1916, the Colorado Supreme Court held that, in deciding whether an act is necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety, the General Assembly “exercises a constitutional power exclusively vested in it, and hence, such declaration is conclusive upon the courts in so far as it abridges the right to invoke the referendum.”

Deciding whether to include a safety clause in a bill is often a matter of timing. If an act is subject to the power of referendum, because it does not include a safety clause, that act cannot take effect for at least 90 days after the end of the legislative session in which it is passed. As previously explained, a citizen has 90 days after the session ends to collect enough signatures to place the act on the ballot. During that time, rather than risk implementing a law that the voters may reverse, the act is held in limbo; it cannot take effect until the time for collecting signatures expires. And if someone does collect enough signatures to put the act on the ballot, it cannot take effect until the Governor declares the vote after the next general election. General elections occur only in even-numbered years, so if an act passes in a legislative session held in an odd-numbered year and is referred to the ballot by petition, the act won’t take effect—if it even takes effect—until roughly 18 months after the end of the legislative session.

Deciding whether to include a safety clause in a bill is often a matter of timing. If an act is subject to the power of referendum, because it does not include a safety clause, that act cannot take effect for at least 90 days after the end of the legislative session in which it is passed. As previously explained, a citizen has 90 days after the session ends to collect enough signatures to place the act on the ballot. During that time, rather than risk implementing a law that the voters may reverse, the act is held in limbo; it cannot take effect until the time for collecting signatures expires. And if someone does collect enough signatures to put the act on the ballot, it cannot take effect until the Governor declares the vote after the next general election. General elections occur only in even-numbered years, so if an act passes in a legislative session held in an odd-numbered year and is referred to the ballot by petition, the act won’t take effect—if it even takes effect—until roughly 18 months after the end of the legislative session.

The last act referred to the ballot was Senate Bill 19-042, which addressed an agreement among the states to elect the President of the United States by national popular vote. The General Assembly passed the act February 22, 2019, the Governor signed it March 15, 2019, but, because it was referred to the ballot, it did not take effect until December 31, 2020.

In contrast, an act that passes with a safety clause may take effect as soon as the Governor either signs it or allows it to become law without signature.

So if the bill sponsor thinks the bill makes a necessary policy change, and it’s important that the change take effect sooner than 90 days after the end of the legislative session, the bill will need a safety clause.

by Jery Payne

It’s a little known fact, but being a smart audience, you may have heard that an epidemic engulfed the nation and the world, which makes the epidemic a pandemic. It’s commonly known as “COVID-19,” which is a shortening of the phrase “Corona Virus Disease of 2019.”

In 2020, the governor of Colorado declared an emergency and invoked emergency powers to address the spread of the virus. The state required people to stay at home as much as possible, mandated people wear masks, and implemented many other mandates. Local health  agencies also issued mandates. This led many people to wonder, “Can they do that?” And like any good lawyer, I’m going to say, “It depends.”

agencies also issued mandates. This led many people to wonder, “Can they do that?” And like any good lawyer, I’m going to say, “It depends.”

The Department of Public Health and Environment and local health agencies have many powers to control epidemics. First, the department has many statutory powers to protect public health, including the power to:

In addition, the department has several statutory powers specific to addressing epidemics, including the power to:

Together, these state statutes give the department broad powers to address epidemics.

Local public health agencies, including county, municipal, and district agencies, also have statutory powers, granted by state law, to control epidemics within their jurisdictions. Local public health agencies have the power to:

Local boards of health are the policy-setting bodies for local health agencies. They develop policies and procedures to address epidemics and to administer and enforce the powers granted to local health agencies. This includes adopting rules and orders. Specifically, local boards of health have the statutory power to:

A person who is negatively affected by a decision, which can be a rule or order of a state or local health board, department, or agency, may seek judicial review. The person must bring the case within 90 days after the decision is publicly announced. The court may affirm the decision or may reverse or modify it if the rights of the person have been prejudiced because the decision is:

Except in certain types of cases, judicial review of a board decision is conducted by the court without a jury. Even when statutory authority exists, a decision that violates the Colorado Constitution or the United States Constitution will be struck down if challenged. If a particular mandate is challenged, the court will review the record to determine whether to uphold or overturn the mandate based on whether the mandate is a reasonable use of the authority to protect public health.

Although my guess is that not many people have flipped through these statute pages for a mighty long spell, you can bet that they have certainly been flipped through a lot lately. These statutes are useful guides as we wend our way through these weird times.

Last week, we brought you part 1 of the Interim Committee Recap series. Today, we’re bringing you part 2, covering the rest of the interim committees and their bills, which were all approved for introduction in the 2022 legislative session at the November 15 Legislative Council meeting.

The Colorado Youth Advisory Council Review Committee met three times during the interim. The committee heard presentations from its student members about youth mental health, higher education tuition waivers for students who have been in foster care, and the Colorado Youth Advisory Council’s enabling legislation. The committee requested the drafting of three bills, one on each of the presented subjects. The committee recommended all three bills to the Legislative Council.

The Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning the Treatment of Persons with Mental Health Disorders in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Systems (committee) met four times during the 2021 interim. The committee heard presentations from multiple stakeholders, mental health advocates, and representatives from state executive departments concerning the issues facing persons with mental health disorders who have been in contact, in one form or another, with the criminal or juvenile justice systems. The committee requested the drafting of 10 bills. Of those, two were withdrawn prior to the September 9, 2021, meeting, three were withdrawn at that meeting, and five bills were recommended by the committee to the Legislative Council for consideration.

The Transportation Legislation Review Committee (TLRC) met at the capitol twice to hear reports and consider legislation and took a few trips to fulfill its statutory authority to review the planning and construction of highway projects. At the hearings, the TLRC heard reports from the Colorado Motor Carriers Association, the Colorado Energy Office and Colorado Department of Transportation, the Regional Transportation District, the Colorado Association of Transit Agencies, the Colorado Cross Disability Coalition, the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing, the Colorado Department of Transportation and the Transportation Commission, the Division of Motor Vehicles, the Department of Public Safety, and the North West Mayors and Commissioners Coalition. The committee also heard reports about public highway authorities, hydrogen development for zero-emission vehicles, and local government use of federal rescue plan funds.

The committee considered and recommended the following legislation:

The Sales and Use Tax Simplification Task Force (SUTSTF) met four times during the 2021 interim and heard briefings and presentations from the Office of Legislative Legal Services, the Colorado Department of Revenue, the Colorado Municipal League, the Colorado Automobile Dealers Association, the Coalition to Simplify Colorado Sales Tax, and members of the public on a variety of topics, including:

The SUTSTF requested the drafting of five bills but recommended only the following three bills to the Legislative Council for introduction:

After a year off, legislative interim committees met this interim to discuss topics relevant to Colorado and to recommend legislation to the Legislative Council Committee. This week, we’re providing a summary of each committee and its recommended legislation. The Legislative Council Committee met on Monday, November 15, and approved all bills recommended to it by the interim committees for introduction in the 2022 legislative session.

For more information about interim committees generally and how they operate, see “Interim Committees: Just the Facts, Ma’am”, posted 7/21/2017.

This interim, the Early Childhood and School Readiness Legislative Commission (Commission) focused its efforts on the transition to the new Department for Early Childhood (DEC) and the creation of the universal preschool program. DEC will coordinate early childhood programs and services throughout Colorado, including the new statewide universal, voluntary preschool program. House Bill 21-1304 established DEC and required the creation of a transition plan, which describes the coordination and administration of early childhood services and programs by DEC and existing departments. On November 18, 2021, the Commission will meet to review the approved transition plan.

During its interim meetings, the Commission heard several presentations centered on workforce updates, reports on home-based child care, and the impacts of COVID-19 on early childhood education. The COVID-19 pandemic not only affected the early childhood educator workforce, but many children also experienced learning loss.

On November 1, 2021, the Commission voted to recommend one bill to the Legislative Council for introduction during the 2022 legislative session:

The Pension Review Commission met twice during the interim. It heard presentations from the Fire and Police Pension Association (FPPA), the Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA), and its own Pension Review Subcommittee. The Pension Review Subcommittee itself met three times to hear presentations from: (1) Gabriel, Roeder, Smith & Company (GRS) regarding its statutorily required independent review of the economic, non-economic, and investment assumptions used to model Colorado PERA’s financial situation; (2) PERA regarding GRS’ recommendations and a general annual update; and (3) the Segal Group, Inc. regarding its summary review of December 31, 2020, actuarial valuation results for PERA’s division trust funds.

The Pension Review Commission requested that three bills be drafted and recommended all of them to the Legislative Council for introduction:

The newly created Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning Tax Policy, a permanent successor to the previous Tax Expenditure Evaluation Interim Study Committee, met five times during its inaugural interim. The committee’s first order of business was to define the scope of tax policies that it and its subordinate Task Force Concerning Tax Policy would consider, and it identified five areas of study, which can be summarized as the income tax base, homestead exemptions, enterprise zones, property tax treatment of short-term rentals, and expanding the sales and use tax to services. The task force has been studying these issues, and presumably, the committee will consider these tax policies after the task force makes its recommendations about them.

In addition, the committee considered the state auditor’s thoughtful and thorough tax expenditure evaluations. After listening and considering the evaluations, the committee approved 10 bills for drafting, of which five were approved as committee bills:

During the 2021 interim, the Water Resources Review Committee (WRRC) held three meetings and took one field trip to the Colorado Water Congress in Steamboat Springs. The WRRC met with a broad range of water users and government officials, including local water providers, water policy experts, state water planners, and concerned citizens. The committee received briefings on major water issues affecting the state, including anti-speculation, recreational in-channel diversion, compact compliance and groundwater challenges, water efficiency in agriculture, dredge and fill permitting, and alternative transfer methods.

On October 27, the WRRC met and voted to advance the following three bills for the consideration of the Legislative Council:

The WRRC also unanimously approved a letter to the Task Force on Economic Recovery and Relief Cash Fund. The letter requested that the Task Force consider water investment in its recommendations.

The Wildfire Matters Review Committee (WMRC) met five times during the 2021 interim. On October 28, 2021, the WMRC voted to advance the following five bills to the Legislative Council:

Where did the interim go? The 2022 Legislative Session will convene at 10 a.m. on Wednesday, January 12, 2022, but, as those who follow the legislature know, bill drafting starts long before that date. Legislators have been submitting bill requests for the upcoming session since the  end of the last session, and interim committees have been meeting and working with drafters since August on committee bill requests. So much is already going on that it might be easy to forget that the first bill request deadline is Wednesday, December 1, 2021. The December deadline is for a legislator’s first three bill requests. After December 1, a legislator may submit up to only two additional bill requests and only to meet the five bill requests allowed by rule.*

end of the last session, and interim committees have been meeting and working with drafters since August on committee bill requests. So much is already going on that it might be easy to forget that the first bill request deadline is Wednesday, December 1, 2021. The December deadline is for a legislator’s first three bill requests. After December 1, a legislator may submit up to only two additional bill requests and only to meet the five bill requests allowed by rule.*

Once a legislator has bill requests in the system, the legislator must choose one of those requests to be a “prefile” bill. The “prefile” bill must be drafted and filed with the House or the Senate for introduction by the Friday before the session convening date. For the upcoming session, the “prefile” bill filing deadline is Friday, January 7, 2022. Generally, the bill deadlines require legislators to have completed, with the help of OLLS drafters, the bulk of their bill drafting well before the first day of the legislative session.

What all legislators need to know about requesting bills [Joint Rule 24 (b)(1)(A)]:

Legislators: If you have not yet submitted a bill request, you are encouraged to submit at least one bill request as soon as possible. Bill requests may address any subject and do not need to be completely conceptualized. The bill drafter can help you figure out how to word your bill, and the bill drafting process allows for potential issues or problems to rise to the surface, making it easier for you to decide whether the idea is “workable.” If a request is no longer needed or wanted, you can withdraw and replace it with a new request, as long as that decision is communicated to the OLLS before the December 1 deadline. By submitting bill requests and draft information as quickly as possible, legislators give drafters more time to work on their bill drafts, make it easier to determine if there are duplicate bill requests, and work out any drafting kinks before the first day of session.

Legislators can submit more than three requests by the December 1 deadline. By doing so, a legislator may have the flexibility to withdraw and replace at least one request after the December deadline without losing a request. If a legislator submits only three requests by December 1 and later withdraws one of them, the legislator forfeits the withdrawn bill request. The rules allow a legislator to submit only two bill requests after the December deadline.* If a legislator submits four bill requests by December 1 and later withdraws one, the legislator is left with three bill requests that met the early request deadline. The legislator can still submit the two requests that are allowed after the early bill request deadline — for a total of five bill requests.

Upcoming deadlines: Too many to remember and too important to forget. Bill request and bill introduction deadlines are listed below. Deadlines that apply only to House bills are in green, deadlines that apply only to Senate bills are in red, and deadlines that apply to both the House and Senate are in blue. Click here for a link to House and Senate bill drafting, finalization, and introduction deadlines. The listed OLLS internal deadlines are designed to allow sufficient time for editing  and review in order to provide a higher-quality work product while still assuring that each bill meets the deadline. Paper copies of these tables are available in the OLLS Front Office, Room 091 of the Capitol.

and review in order to provide a higher-quality work product while still assuring that each bill meets the deadline. Paper copies of these tables are available in the OLLS Front Office, Room 091 of the Capitol.

December deadlines:*

December 1. The last day for legislators to request their first three (or early) bill requests. After December 1, legislators are only allowed two additional bill requests (only if they are under the five-bill limit).

Upcoming filing and introduction deadlines:*

January 7. Deadline to file prefile bills with House and Senate front desks.

January 14. Deadline to file Senate early bills with the Senate front desk.

January 18. Deadline to request last two bills (regular bills) if a legislator is under the five-bill limit.

January 18. Deadline to file House early bills with the House front desk.

January 28. Deadline to file Senate regular bills with the Senate front desk.

February 2. Deadline to file House regular bills with the House front desk.

Click here for the Deadline Schedule for the 2022 Legislative Session.

* A legislator may seek permission from the House or Senate Committee on Delayed Bills, whichever is appropriate, to submit additional bill requests or to waive a bill request deadline.

by Patti Dahlberg

Colorado’s weather has set numerous records for highs, lows, and coldest months on record over the past year or so. Just two years ago, we experienced an unheard of “bomb cyclone” snowstorm, severely testing Coloradans’ ability to navigate gusting winds, at times up to 96 mph, creating blizzard conditions, and virtually shutting down all transportation in Denver. The bomb cyclone designation referred to the 30-degree drop in the barometric pressure that day, to 970.4. (Low barometric pressures are typically associated with Category 2 or 3 hurricanes.) It was a record day in Colorado for extreme weather, but 1921 also had its share of extreme weather records in Colorado and across the country.

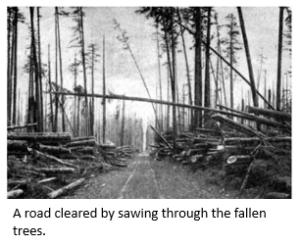

Grays Harbor, Washington. The year started with the “Great Blowdown.” Around noon on January 29, 1921, the wind began hitting Grays Harbor, at that time considered the largest lumber shipyard in the world. By 2:00 p.m., the Olympic Peninsula felt the full force of an extreme  windstorm, considered by some a cyclone and by others a tornado. Hurricane-force winds raked the shores of the Pacific Northwest from central Oregon to the Canadian border. The storm came without warning, and within a few hours gusts were reaching an estimated 150 mph — estimated, because the instrument measuring the wind gusts was carried away after measuring 126 mph. The storm blew down timber in a 2,000-square-mile area, toppling more than 40 percent of the trees on the southwest side of the Olympic Mountains. Some of the trees blown over measured 12 feet in diameter, with top-heavy and shallow-rooted great spruces particularly vulnerable. Hundreds of farm and forest animals were killed by falling tree branches and flying debris, but amazingly, only one person was killed during the storm, although several were injured.

windstorm, considered by some a cyclone and by others a tornado. Hurricane-force winds raked the shores of the Pacific Northwest from central Oregon to the Canadian border. The storm came without warning, and within a few hours gusts were reaching an estimated 150 mph — estimated, because the instrument measuring the wind gusts was carried away after measuring 126 mph. The storm blew down timber in a 2,000-square-mile area, toppling more than 40 percent of the trees on the southwest side of the Olympic Mountains. Some of the trees blown over measured 12 feet in diameter, with top-heavy and shallow-rooted great spruces particularly vulnerable. Hundreds of farm and forest animals were killed by falling tree branches and flying debris, but amazingly, only one person was killed during the storm, although several were injured.

Silver Lake, Colorado. On April 14 and 15 of 1921, a major winter storm slammed the Front Range of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, leaving more than 6 feet of snow in a 24-hour period. The 75.8 inches of measured snow that fell in a 24-hour period at Silver Lake in Boulder County remains the record for the most snowfall in a 24-hour period in the United States. Silver Lake’s snow totals continued to grow to 87 inches in 28 hours, and then 95 inches in 32 hours (that’s almost 8 feet of snow). Meanwhile, in Denver, only about 10 inches of snow fell, but the 50-mph winds accompanying the storm created snowdrifts throughout the city, some as high as 7 feet, and caused damage to trees, utility poles, and buildings.

Pueblo, Colorado. During a typical summer cloudburst, more than half an inch of rain may fall in a matter of minutes, and that is exactly what happened in Pueblo on June 3, 1921, this time creating devastating consequences for the city. Beginning the day before, torrential rains began swelling creeks and streams throughout the Arkansas River drainage system. Fountain Creek, running south from Colorado Springs, overflowed its banks, and mountain tributaries of the Arkansas River reached flood stage. Mountain reservoirs failed, and a cresting flood, over 15 feet deep at times, moved swiftly down the Arkansas River on the afternoon of June 3, sweeping through Pueblo’s business and commercial district that evening. Two thousand railcars were smashed, overturned, or carried away. Eight of the nine bridges across the Arkansas River and Fountain Creek were seriously damaged or washed away. Hundreds of buildings were lost, including more than 500 houses and almost 100 businesses. Fires raged in the upper floors of flooded structures as houses and boxcars floated down Pueblo’s South Union Avenue. Telephone lines were destroyed, so there was little to no communication between Pueblo and the rest of the state. There was no official rainfall report for Pueblo at the time, but records from private citizens indicated that a total of 6 inches or more fell between June 3 and June 5.

The 1921 Pueblo flood was the worst disaster in the history of Colorado. The floodplain covered more than 300 square miles, and the flood toll stood at 262 people dead, missing, or unaccounted for. The actual death toll was likely much higher because for several years, human remains were found many miles downstream. Much of the downtown area was destroyed, farmlands east and south of the Steel City were flooded, irrigation structures were wrecked, and Pueblo’s economy was dealt a long-lasting blow. Subsequent estimates of property damages and losses from the flood ranged from $13 to $19 million in a city whose assessed valuation in 1921 was just over $33 million. The 1921 flood was the worst of many floods on the Arkansas River, which averaged one flood every 10 years until the Pueblo Dam was completed in 1975.

Tampa Bay, Florida. On October 25, 1921, Tampa Bay suffered the most destructive hurricane to hit the area since 1848. A 10- to 12-foot storm surge destroyed substantial portions of the seawall along coastal locations. Many vessels were smashed against the docks by the waves, and area citrus crops were destroyed. Powerful winds brought heavy damage to structures along the bay. Without the weather forecasting support of the satellites, radar, computer graphics, and mathematical models we have today, advance warning for such an event was extremely difficult. Most hurricane “forecasting” at that time was based on data from previous hurricanes moving through the Gulf of Mexico, which normally landed far north of the Tampa area. There were eight confirmed fatalities, mostly from drowning.

Outer space (yep – outer space). From May 13 to 16, 1921, one of the two largest known solar storms burst from the sun and soared across space to create some havoc on Earth. This 1921 solar storm, called the New York Railroad Storm because of the disruption to trains in New York City following a fire in a control tower on May 15, unfolded in two phases, unleashing an opening burst of disruption before intensifying into a full-fledged superstorm. In reconstructing the timeline of the storm from scientific journals, newspapers, and other sources, it is believed that three major fires erupted on the same day. One, sparked by strong currents in telegraph wires at a railroad station in Brewster, N.Y., burned the station to the ground. The second fire destroyed a telephone exchange in Karlstad, Sweden, while the third occurred in Ontario. Telegraph systems and telephone lines were disrupted in the U.K., New Zealand, Denmark, Japan, Brazil, and Canada. It wasn’t all bad news: many locations around the world recorded sightings of spectacular auroras. Auroras were recorded near Paris, in Arizona, and in Samoa, which is not far from the equator. It is widely believed that if the 1921 storm occurred today, there would be widespread interference with our modern technology systems and widespread disruption of services.

Outer space (yep – outer space). From May 13 to 16, 1921, one of the two largest known solar storms burst from the sun and soared across space to create some havoc on Earth. This 1921 solar storm, called the New York Railroad Storm because of the disruption to trains in New York City following a fire in a control tower on May 15, unfolded in two phases, unleashing an opening burst of disruption before intensifying into a full-fledged superstorm. In reconstructing the timeline of the storm from scientific journals, newspapers, and other sources, it is believed that three major fires erupted on the same day. One, sparked by strong currents in telegraph wires at a railroad station in Brewster, N.Y., burned the station to the ground. The second fire destroyed a telephone exchange in Karlstad, Sweden, while the third occurred in Ontario. Telegraph systems and telephone lines were disrupted in the U.K., New Zealand, Denmark, Japan, Brazil, and Canada. It wasn’t all bad news: many locations around the world recorded sightings of spectacular auroras. Auroras were recorded near Paris, in Arizona, and in Samoa, which is not far from the equator. It is widely believed that if the 1921 storm occurred today, there would be widespread interference with our modern technology systems and widespread disruption of services.

Resources:

by Conrad Imel

In 1861, when botanist Dr. Charles C. Parry was on his first botanical exploration of the Rocky Mountain region in Colorado, two tall mountain peaks attracted the doctor’s attention. Following the practice among botanists to name new plants after each other, Dr. Parry named the peaks after two of his colleagues, Asa Gray and John Torrey. Today, Grays Peak and Torreys Peak, the two “14ers” that sit just west of Denver, are popular with hikers, in part because their proximity allows a hiker to summit both in one day. If you (or anyone in  OLLS… hint, hint) wanted to name a mountain after a colleague, how would you go about it? The answer is a little fuzzy, but let’s see if LegiSource can help make sense of it.

OLLS… hint, hint) wanted to name a mountain after a colleague, how would you go about it? The answer is a little fuzzy, but let’s see if LegiSource can help make sense of it.

Neither the state nor the federal government has the exclusive authority to name a mountain, so the General Assembly could take steps to rename a mountain for state purposes. But it’s likely the best approach is to work through the federal board responsible for naming geographic features for federal purposes. The names bestowed by the federal board are used on federal maps and often followed by state and local governments.

Federal renaming process

Geographic names, including names of mountains, specifically established by federal law or executive order are official for federal purposes and can only be changed by federal law or subsequent order. But many federally recognized geographic names aren’t established by Congress or the President, they are approved by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN). Congress established the current BGN in 1947 to promote uniformity within the federal government in naming geographic features. The BGN’s decisions only apply to the federal government; state and local governments generally use the federal names, but there is no law requiring them to do so.

The BGN does not create names for geographic features; it approves or rejects names proposed by others, based on the BGN’s principles, policies, and procedures. For domestic names, anyone can suggest a name for approval by submitting a proposal online or printing and completing a Domestic Geographic Name Proposal form. After receiving a suggestion, the BGN will conduct an investigation to ensure the suggestion conforms to BGN policies. It will also receive input from the general public; state naming authorities; interested federal, state, and local agencies; and federally recognized Indian tribes.

You probably haven’t noticed any changes to the names of Colorado landmarks lately, and there’s a reason for that. As part of the name change process, the BGN works with the state naming authority in the state where the geographic feature resides. Colorado’s state naming authority was disbanded in 2013, so the BGN ceased working on name changes for features within the state. But fear not, on July 2, 2020, Governor Polis established a new Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board that will work with the BGN. BGN staff has met with Colorado’s board to discuss a strategy for addressing the backlog of pending Colorado renaming cases, and the Colorado board recently made its first name change recommendation. On September 16, 2021, the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board recommended changing the name of Squaw Mountain in Clear Creek County to Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain.

State Geographic Naming

Since the federal government does not have exclusive authority to name a geographic feature, states like Colorado can name (or rename) a mountain for state purposes. While there is no formal Colorado process for changing a name, there are historic examples where the General Assembly named a Colorado mountain peak, including some that occurred after the establishment of the modern BGN. The General Assembly adopted joint resolutions to name Mount Evans in 1895; rename Mount Wilson as Mount Franklin Roosevelt in 1937; and, in 1978, rename Lone Eagle Peak (named to honor Charles A. Lindbergh who had been known by the nickname “Lone Eagle”) as Lindbergh Peak. The 1978 Lindbergh Peak resolution directed that a copy of the resolution be sent to the BGN. In 1949, the General Assembly passed a bill to rename Veta Peak as Mount Mestas.

More recently, in 1995, the Colorado Senate approved a resolution supporting the efforts to name a mountain peak in honor of one of Colorado’s legendary early mountain climbers, Carl Albert Blaurock. Eight years later, on October 1, 2003, to honor Blaurock’s legacy of climbing, the BGN approved naming a 13,616-foot peak in Colorado’s Collegiate Peaks range as Mount Blaurock.

More recently, in 1995, the Colorado Senate approved a resolution supporting the efforts to name a mountain peak in honor of one of Colorado’s legendary early mountain climbers, Carl Albert Blaurock. Eight years later, on October 1, 2003, to honor Blaurock’s legacy of climbing, the BGN approved naming a 13,616-foot peak in Colorado’s Collegiate Peaks range as Mount Blaurock.

Another wrinkle in a state-specific renaming is that some mountains are in similarly named federal lands. For example, Mount Evans sits in the federal Mount Evans National Wilderness Area. Even if Colorado changed the name of the mountain for state purposes, it could not change the name of the national wilderness area, which was designated by Congress.

Because it would not affect federal maps, signage, documents, or federally named lands, an exclusively state-based solution may not be the best approach for widespread acceptance of a new mountain name. Instead, working through the BGN’s process will get your (or your colleague’s) name on the map. While the federal renaming process can be lengthy, the first step is simple: head to the BGN’s website to review its policies and make a suggestion. If you’re a member of the General Assembly who would like to draft a resolution to change a mountain name at the state level, or suggest or support a federal change, please contact OLLS to put in your request.

Research from Nate Carr and Jacob Baus was used in this post.

by Bob Lackner

As we covered in our last article, in SB21-137, SB21-291, and HB21-1329, the General Assembly created task forces to meet in the 2021 interim and make recommendations concerning how to spend the remaining ARPA funds. Here, we explain those task forces in more detail.

The federal regulations construing ARPA specify in relevant part that funds may be used for programs or services that address housing insecurity, lack of affordable and workplace housing, or homelessness, including:

HB21-1329 requires the executive committee of the legislative council (executive committee), by resolution, to create a task force to meet during the 2021 interim and issue a report with recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor on policies to create transformative change in the area of housing (Housing Task Force) using the money the state receives from the ARPA fund, which would include the money transferred into the affordable housing and home ownership cash fund.[1] Essentially, the Housing Task Force is to advise the General Assembly and the Governor on how best to spend the remaining $400 million or so now sitting in the affordable housing and home ownership cash fund that the state has received from the ARPA fund and that was not appropriated in the 2021 regular legislative session.[2]

Similarly, SB21-137 requires the executive committee to create a task force to meet during the 2021 interim and issue a report with recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor on policies to create transformative change in the area of behavioral health (Behavioral Health Task Force) using the money the state receives from the ARPA fund.

SB21-291 requires the executive committee, by resolution, to create a task force to meet during the 2021 interim (Economic Recovery Task Force) and issue a report with recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor on policies that use money from the economic recovery and relief cash fund to help stimulate the state’s economy, provide necessary relief for Coloradans, or address emerging economic disparities resulting from the pandemic.

All three bills specify that their respective task forces may include nonlegislative members and create working groups to assist their work. In addition, HB21-1329 and SB21-137 direct the executive committee to hire a facilitator to guide the work of the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces. The executive committee hired Wellstone Collaborative Strategies as the facilitator.

The executive committee has issued resolutions creating the Housing, Behavioral Health, and Economic Recovery Task Forces .[3] Both the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces consist of 16 members, ten of whom are appointed by majority and minority leadership of the General Assembly. The other six members of the respective task forces are various state officials with responsibility for setting and administering state policy on housing or behavioral health matters, as applicable. In accordance with HB21-1329 and SB21-137, the Housing and Behavioral Health Resolutions created the Affordable Housing Transformational Task Force Subpanel (Housing Subpanel) and the Behavioral Health Transformational Task Force (Behavioral Health Subpanel), respectively. Both subpanels are directed to meet during the 2021 interim to make recommendations to the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces on policies to create transformational change in the area of housing and behavioral health, as applicable, using money from the ARPA fund.

The Housing Subpanel consists of 15 members. Five members of the Housing Subpanel are appointed by the Senate President. Six members are appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The Minority Leaders of the Senate and House of Representatives are each entitled to appoint two additional members of the task force. Members appointed to the Housing Subpanel must represent various groups and stakeholders and must possess knowledge or expertise in housing issues as specified in the Housing Resolution.

The Behavioral Health Subpanel consists of 25 members, nine of whom are to be appointed by the Senate president and eight to be appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The Minority Leaders of the Senate and the House of Representatives are each entitled to appoint four additional members of the subpanel. As with the Housing Subpanel, members of the Behavioral Health Subpanel must represent various groups and stakeholders and must possess knowledge or expertise in behavioral health issues as specified in the Behavioral Health Resolution.

Under the applicable resolutions, both the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces may meet up to ten times during the 2021 interim and the subpanels are required to meet up to 16 times in the 2021 interim. The Housing and Behavioral Health Subpanels are directed to make recommendations to their governing task forces for review, consideration, and approval by those bodies. Both the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces are directed to approve recommendations and the final report of each task force by a majority vote of all members of the body.

The Economic Recovery Task Force consists of eight members, six of whom are appointed by the Majority and Minority leadership of the two chambers. The executive director of the Office of Economic Development and International Trade (OEDIT) and the executive director of the Office of State Planning and Budgeting (or their designees) fill out the remaining appointments to this Task Force. The resolution creating the Economic Recovery Task Force also creates the Economic Recovery and Relief Cash Fund Subpanel (Economic Recovery Subpanel) to meet during the 2021 interim to make recommendations to the Economic Recovery Task Force on policies that use money from the economic recovery and relief cash fund to help stimulate the state’s economy, provide necessary relief for Coloradans, or address emerging economic disparities resulting from the pandemic. The Economic Recovery Subpanel consists of five members, all of whom are required to be economists. Of the five appointments, the Senate President and House Speaker must jointly make two appointments, the Senate and House Minority leaders must jointly make one appointment, the Governor is to make one appointment, and the final appointment must come from OEDIT.

The Economic Recovery Task Force and Subpanel may each meet up to four times during the 2021 interim. This task force is also directed to approve the final report of the task force by a majority vote of all members of the body.

The Economic Recovery Resolution also directs the Economic Recovery Subpanel to analyze and synthesize data on the current state of the state’s economy, identify ongoing challenges with the state’s recovery and opportunities for larger growth in specific sectors or industries, and outline the underlying issues that are contributing to the overall economic gaps that are inhibiting recovery and growth.

In addition, all three resolutions direct state departments and agencies with relevant information to provide assistance and information to the respective task forces and subpanels. With respect to the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces, staff from the legislative service agencies will provide support to the respective task forces and subpanels, except for those responsibilities delegated to the facilitators as specified in the requests for information issued for facilitation services. In the case of the Economic Recovery Task Force, the resolution directs the Legislative Council Staff Chief Economist, or his or her designee, to provide information and assistance to the Economic Recovery Subpanel in completing its duties relating to the analysis and synthesis of the state’s economic data.

Both HB21-1329 and SB21-137 specify that the respective task forces are not subject to section 2-3-303.3, C.R.S., or Joint Rule 24A of the Joint Rules of the Senate and the House of Representatives, both of which govern the conduct of interim committees. This means these bodies will not be treated as regular interim committees and subject to the regular procedural and bill drafting requirements to which interim committees are subject.[4] Instead, both bills specify that the executive committee is to specify requirements governing members’ participation in the work of the respective task forces. Notably, all three bills also specify that the respective task forces are not to submit bill drafts as part of their recommendations.

Both the Housing and Behavioral Health Resolutions direct the respective task forces to finalize their recommendations by January 11, 2022, and to submit their reports to the General Assembly and the Governor no later than January 21, 2022. Under the Economic Recovery Task Force resolution, the task force is required to finalize its recommendations by December 17, 2021, and to submit its recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor by January 13, 2022.

A different process is mandated by SB21-291 for the Economic Recovery Task Force. With respect to that body, the staff of the Joint Budget Committee will review the task force’s recommendations to ascertain whether the recommendations will result in programs requiring ongoing appropriations of state money after the federal money has been expended and to identify whether the recommendations are duplicative of any existing state programs or appropriations or duplicative of any existing federally funded state program. [5]

It is expected that a major focus of the 2022 regular legislative session will be the drafting and consideration of legislative proposals to implement the recommendations of these task forces and subpanels in the important areas of affordable housing, behavioral health, and economic recovery.

[1] Under the legislation, the General Assembly is also required to review recommendations for policies to create transformative change in the area of housing submitted by the Strategic Housing Working Group assembled by the Department of Local Affairs and the State Housing Board.

[2] In particular, of the $550 million the state received from ARPA for housing purposes, for the 2021-22 state fiscal year, $98.5 million was appropriated to the Division of Housing in the Department of Local Affairs to expend on programs or services of the type and kind financed through the housing investment trust fund and the housing development grant fund to support programs or services that benefit populations, households, or geographic areas disproportionately affected by the COVID public health emergency to obtain affordable housing, focusing on housing insecurity, lack of affordable and workforce housing, and homelessness. In addition, $1.5 million was appropriated to the state judicial department for use by the eviction legal defense fund to provide legal representation to indigent tenants. Money from the ARPA fund was also used to finance other affordable-housing-related purposes.

[3] Resolution of the Executive Committee of the Legislative Council, Affordable Housing Transformational Task Force, Updated July 30, 2021 (Housing Resolution);

[4] SB21-291 fails to specify whether the Economic Recovery Task Force is subject to the normal interim committee requirements but, as with the other two bills, does state that the executive committee will specify requirements for members’ participation in the body.

[5] The Economic Recovery Resolution summarizes this requirement as follows: “JBC Staff will review the Task Force report to offer analysis on whether programs already exist that would have overlapping missions, and whether anything would likely entail ongoing General Fund obligations.”