by Conrad Imel

Often the General Assembly passes bills to regulate future conduct, but sometimes a legislator wants to expressly address something that happened in the past. The Colorado Constitution limits the General Assembly’s power to enact legislation that applies retroactively, so we at LegiSource are here to help make sense of these limits on the General Assembly’s authority.

The General Assembly has broad plenary authority to enact legislation, but that power is limited by state and federal constitutional provisions. One such provision is the Colorado Constitution’s retrospectivity clause. Article II, section 11 of the Colorado Constitution states:

No ex post facto law, nor law impairing the obligation of contracts, or retrospective in its operation, or making any irrevocable grant of special privileges, franchises or immunities, shall be passed by the general assembly. (emphasis added)

Recently, in Aurora Public Schools v. A.S., the Colorado Supreme Court had occasion to outline the contours of this retrospectivity clause. Aurora Public Schools involved a challenge to the constitutionality of Senate Bill 21-088. That bill created a new statutory cause of action for victims of sexual misconduct that occurred while the victim was a minor. Like most laws, S.B. 21-088 applies prospectively, to conduct that occurs after the bill’s effective date. However, S.B. 21-088 also expressly applies retroactively. The bill created a three-year “look back” window for victims of misconduct that occurred between January 1, 1960, and January 1, 2022 (the bill’s effective date). The look-back provision allowed victims of past misconduct to bring a claim during the three-year period between January 1, 2022, and January 1, 2025. The plaintiffs in Aurora Public Schools brought a claim pursuant to the look-back provision; the defendants moved to dismiss the case, claiming that the look-back window was unconstitutionally retrospective.

that occurs after the bill’s effective date. However, S.B. 21-088 also expressly applies retroactively. The bill created a three-year “look back” window for victims of misconduct that occurred between January 1, 1960, and January 1, 2022 (the bill’s effective date). The look-back provision allowed victims of past misconduct to bring a claim during the three-year period between January 1, 2022, and January 1, 2025. The plaintiffs in Aurora Public Schools brought a claim pursuant to the look-back provision; the defendants moved to dismiss the case, claiming that the look-back window was unconstitutionally retrospective.

The Court in Aurora Public Schools began by explaining the retrospectivity clause and reaffirming its prior retrospectivity jurisprudence. The Court explained that the purpose of the retrospectivity clause is to prevent unfairness that would otherwise result from “changing the consequences of an act after that act has occurred. [. . .] In other words, the prohibition on retrospective legislation prevents the legislature from changing the rules after the fact because to do so would be unjust.”

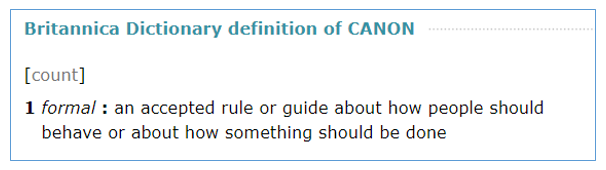

But not all retroactive legislation is unconstitutionally retrospective. To determine whether a retroactive law is unconstitutionally retrospective, Colorado courts use the “Story test,”[1] which says that a law violates article II, section 11’s prohibition if it (1) impairs a vested right; or (2) creates a new obligation, imposes a new duty, or attaches a new disability with respect to transactions or considerations already past. While these two prongs arguably overlap, a law that satisfies either prong is unconstitutionally retrospective. The focus of the test is on substantive laws. Laws that are merely procedural or remedial may apply retroactively without offending the constitution.

The plaintiffs in Aurora Public Schools argued that there is a public policy exception to the prohibition on retrospective legislation, but the Court disagreed, holding that there is no public policy exception to the retrospectivity clause.

Ultimately, the Court held that S.B. 21-088’s look-back window is unconstitutional in violation of the retrospectivity clause to the extent that it permits a victim to bring a claim for past sexual misconduct for which previously available causes of action were barred by the statute of limitations. The court found that the bill created a new right for relief for the plaintiffs, which in turn created a new obligation and disability with respect to past transactions for the defendants, in violation of the retrospectivity clause. Further, the court affirmed past precedent that the retrospectivity clause prohibits reviving claims that are time-barred by the statute of limitations and found that the three-year look-back window to bring a new cause of action for past conduct indirectly accomplishes the same ends as reviving a claim that is time-barred.

So what does the Court’s opinion in Aurora Public Schools mean for the General Assembly? First, the Court made clear that Colorado courts will use the “Story test” to determine the constitutionality of a law that applies retroactively and that there is no public policy exception to the retrospectivity clause. Second, the Court explained that the retrospectivity clause prohibits the legislature from doing something indirectly which it could not do directly, so the retrospectivity analysis applies to any law that applies retroactively.

The constitution does not completely prohibit the General Assembly from enacting laws that apply to conduct that occurred prior to the law going into effect, but it does prohibit laws that impair a vested right or create a new obligation, impose a new duty, or attach a new disability to past conduct. If a member wants to sponsor a bill that applies retroactively, the bill drafter can help walk the sponsor through any constitutional concerns.

To read more about the Colorado constitution’s ex post facto clause (i.e., section 11 of article II), see https://legisource.net/2014/09/25/ex-post-facto-laws-effective-dates-and-legislative-time-travel/ .

[1] The “Story test” is named for United States Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, who first articulated the test in Society for the Propagation of the Gospel v. Wheeler, 22 F.Cas. 756 (C.C.D.N.H. 1814).