by Bob Lackner

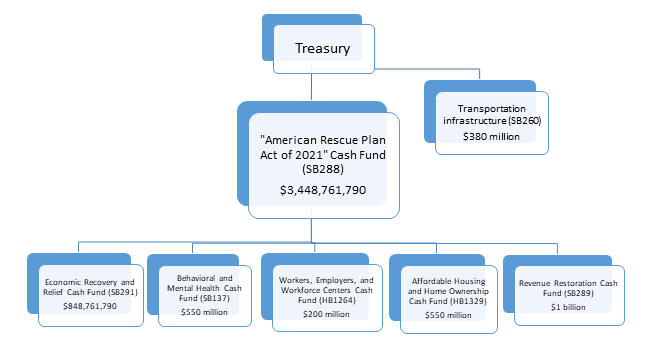

As we covered in our last article, in SB21-137, SB21-291, and HB21-1329, the General Assembly created task forces to meet in the 2021 interim and make recommendations concerning how to spend the remaining ARPA funds. Here, we explain those task forces in more detail.

The federal regulations construing ARPA specify in relevant part that funds may be used for programs or services that address housing insecurity, lack of affordable and workplace housing, or homelessness, including:

- Supportive housing or other programs or services to improve access to stable, affordable housing among unhoused individuals;

- The development of affordable housing; and

- Housing vouchers and assistance to allow individuals to relocate in neighborhoods with high levels of economic opportunity and to reduce concentrated levels of low economic opportunity.

HB21-1329 requires the executive committee of the legislative council (executive committee), by resolution, to create a task force to meet during the 2021 interim and issue a report with recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor on policies to create transformative change in the area of housing (Housing Task Force) using the money the state receives from the ARPA fund, which would include the money transferred into the affordable housing and home ownership cash fund.[1] Essentially, the Housing Task Force is to advise the General Assembly and the Governor on how best to spend the remaining $400 million or so now sitting in the affordable housing and home ownership cash fund that the state has received from the ARPA fund and that was not appropriated in the 2021 regular legislative session.[2]

Similarly, SB21-137 requires the executive committee to create a task force to meet during the 2021 interim and issue a report with recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor on policies to create transformative change in the area of behavioral health (Behavioral Health Task Force) using the money the state receives from the ARPA fund.

SB21-291 requires the executive committee, by resolution, to create a task force to meet during the 2021 interim (Economic Recovery Task Force) and issue a report with recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor on policies that use money from the economic recovery and relief cash fund to help stimulate the state’s economy, provide necessary relief for Coloradans, or address emerging economic disparities resulting from the pandemic.

All three bills specify that their respective task forces may include nonlegislative members and create working groups to assist their work. In addition, HB21-1329 and SB21-137 direct the executive committee to hire a facilitator to guide the work of the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces. The executive committee hired Wellstone Collaborative Strategies as the facilitator.

The executive committee has issued resolutions creating the Housing, Behavioral Health, and Economic Recovery Task Forces .[3] Both the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces consist of 16 members, ten of whom are appointed by majority and minority leadership of the General Assembly. The other six members of the respective task forces are various state officials with responsibility for setting and administering state policy on housing or behavioral health matters, as applicable. In accordance with HB21-1329 and SB21-137, the Housing and Behavioral Health Resolutions created the Affordable Housing Transformational Task Force Subpanel (Housing Subpanel) and the Behavioral Health Transformational Task Force (Behavioral Health Subpanel), respectively. Both subpanels are directed to meet during the 2021 interim to make recommendations to the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces on policies to create transformational change in the area of housing and behavioral health, as applicable, using money from the ARPA fund.

The Housing Subpanel consists of 15 members. Five members of the Housing Subpanel are appointed by the Senate President. Six members are appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The Minority Leaders of the Senate and House of Representatives are each entitled to appoint two additional members of the task force. Members appointed to the Housing Subpanel must represent various groups and stakeholders and must possess knowledge or expertise in housing issues as specified in the Housing Resolution.

The Behavioral Health Subpanel consists of 25 members, nine of whom are to be appointed by the Senate president and eight to be appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The Minority Leaders of the Senate and the House of Representatives are each entitled to appoint four additional members of the subpanel. As with the Housing Subpanel, members of the Behavioral Health Subpanel must represent various groups and stakeholders and must possess knowledge or expertise in behavioral health issues as specified in the Behavioral Health Resolution.

Under the applicable resolutions, both the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces may meet up to ten times during the 2021 interim and the subpanels are required to meet up to 16 times in the 2021 interim. The Housing and Behavioral Health Subpanels are directed to make recommendations to their governing task forces for review, consideration, and approval by those bodies. Both the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces are directed to approve recommendations and the final report of each task force by a majority vote of all members of the body.

The Economic Recovery Task Force consists of eight members, six of whom are appointed by the Majority and Minority leadership of the two chambers. The executive director of the Office of Economic Development and International Trade (OEDIT) and the executive director of the Office of State Planning and Budgeting (or their designees) fill out the remaining appointments to this Task Force. The resolution creating the Economic Recovery Task Force also creates the Economic Recovery and Relief Cash Fund Subpanel (Economic Recovery Subpanel) to meet during the 2021 interim to make recommendations to the Economic Recovery Task Force on policies that use money from the economic recovery and relief cash fund to help stimulate the state’s economy, provide necessary relief for Coloradans, or address emerging economic disparities resulting from the pandemic. The Economic Recovery Subpanel consists of five members, all of whom are required to be economists. Of the five appointments, the Senate President and House Speaker must jointly make two appointments, the Senate and House Minority leaders must jointly make one appointment, the Governor is to make one appointment, and the final appointment must come from OEDIT.

The Economic Recovery Task Force and Subpanel may each meet up to four times during the 2021 interim. This task force is also directed to approve the final report of the task force by a majority vote of all members of the body.

The Economic Recovery Resolution also directs the Economic Recovery Subpanel to analyze and synthesize data on the current state of the state’s economy, identify ongoing challenges with the state’s recovery and opportunities for larger growth in specific sectors or industries, and outline the underlying issues that are contributing to the overall economic gaps that are inhibiting recovery and growth.

In addition, all three resolutions direct state departments and agencies with relevant information to provide assistance and information to the respective task forces and subpanels. With respect to the Housing and Behavioral Health Task Forces, staff from the legislative service agencies will provide support to the respective task forces and subpanels, except for those responsibilities delegated to the facilitators as specified in the requests for information issued for facilitation services. In the case of the Economic Recovery Task Force, the resolution directs the Legislative Council Staff Chief Economist, or his or her designee, to provide information and assistance to the Economic Recovery Subpanel in completing its duties relating to the analysis and synthesis of the state’s economic data.

Both HB21-1329 and SB21-137 specify that the respective task forces are not subject to section 2-3-303.3, C.R.S., or Joint Rule 24A of the Joint Rules of the Senate and the House of Representatives, both of which govern the conduct of interim committees. This means these bodies will not be treated as regular interim committees and subject to the regular procedural and bill drafting requirements to which interim committees are subject.[4] Instead, both bills specify that the executive committee is to specify requirements governing members’ participation in the work of the respective task forces. Notably, all three bills also specify that the respective task forces are not to submit bill drafts as part of their recommendations.

Both the Housing and Behavioral Health Resolutions direct the respective task forces to finalize their recommendations by January 11, 2022, and to submit their reports to the General Assembly and the Governor no later than January 21, 2022. Under the Economic Recovery Task Force resolution, the task force is required to finalize its recommendations by December 17, 2021, and to submit its recommendations to the General Assembly and the Governor by January 13, 2022.

A different process is mandated by SB21-291 for the Economic Recovery Task Force. With respect to that body, the staff of the Joint Budget Committee will review the task force’s recommendations to ascertain whether the recommendations will result in programs requiring ongoing appropriations of state money after the federal money has been expended and to identify whether the recommendations are duplicative of any existing state programs or appropriations or duplicative of any existing federally funded state program. [5]

It is expected that a major focus of the 2022 regular legislative session will be the drafting and consideration of legislative proposals to implement the recommendations of these task forces and subpanels in the important areas of affordable housing, behavioral health, and economic recovery.

[1] Under the legislation, the General Assembly is also required to review recommendations for policies to create transformative change in the area of housing submitted by the Strategic Housing Working Group assembled by the Department of Local Affairs and the State Housing Board.

[2] In particular, of the $550 million the state received from ARPA for housing purposes, for the 2021-22 state fiscal year, $98.5 million was appropriated to the Division of Housing in the Department of Local Affairs to expend on programs or services of the type and kind financed through the housing investment trust fund and the housing development grant fund to support programs or services that benefit populations, households, or geographic areas disproportionately affected by the COVID public health emergency to obtain affordable housing, focusing on housing insecurity, lack of affordable and workforce housing, and homelessness. In addition, $1.5 million was appropriated to the state judicial department for use by the eviction legal defense fund to provide legal representation to indigent tenants. Money from the ARPA fund was also used to finance other affordable-housing-related purposes.

[3] Resolution of the Executive Committee of the Legislative Council, Affordable Housing Transformational Task Force, Updated July 30, 2021 (Housing Resolution);

Resolution of the Legislative Council, Behavioral Health Transformational Task Force, updated July 30, 2021 (Behavioral Health Resolution)

Resolution of the Executive Committee of the Legislative Council, Economic Relief and Recovery Task Force, August 26, 2021 (Economic Recovery Resolution)

[4] SB21-291 fails to specify whether the Economic Recovery Task Force is subject to the normal interim committee requirements but, as with the other two bills, does state that the executive committee will specify requirements for members’ participation in the body.

[5] The Economic Recovery Resolution summarizes this requirement as follows: “JBC Staff will review the Task Force report to offer analysis on whether programs already exist that would have overlapping missions, and whether anything would likely entail ongoing General Fund obligations.”

When first approved in 1876, the Colorado Constitution placed the legislative power of the state solely in the hands of the elected members of the Colorado House and Senate. And that’s where it stayed for almost 35 years. But by the early twentieth century, many people had become disillusioned with government; they no longer trusted elected officials to act solely in the public interest. The progressive movement arose, and the people started demanding a role for themselves in making the laws. They wanted to put the “demo” back in democracy. At the general election held in 1910, Colorado voters adopted an amendment to the Colorado Constitution—placed on the ballot by the General Assembly—that put the power to make laws directly in the hands of the people through the twin powers of initiative and referendum.

When first approved in 1876, the Colorado Constitution placed the legislative power of the state solely in the hands of the elected members of the Colorado House and Senate. And that’s where it stayed for almost 35 years. But by the early twentieth century, many people had become disillusioned with government; they no longer trusted elected officials to act solely in the public interest. The progressive movement arose, and the people started demanding a role for themselves in making the laws. They wanted to put the “demo” back in democracy. At the general election held in 1910, Colorado voters adopted an amendment to the Colorado Constitution—placed on the ballot by the General Assembly—that put the power to make laws directly in the hands of the people through the twin powers of initiative and referendum. Deciding whether to include a safety clause in a bill is often a matter of timing. If an act is subject to the power of referendum, because it does not include a safety clause, that act cannot take effect for at least 90 days after the end of the legislative session in which it is passed. As previously explained, a citizen has 90 days after the session ends to collect enough signatures to place the act on the ballot. During that time, rather than risk implementing a law that the voters may reverse, the act is held in limbo; it cannot take effect until the time for collecting signatures expires. And if someone does collect enough signatures to put the act on the ballot, it cannot take effect until the Governor declares the vote after the next general election. General elections occur only in even-numbered years, so if an act passes in a legislative session held in an odd-numbered year and is referred to the ballot by petition, the act won’t take effect—if it even takes effect—until roughly 18 months after the end of the legislative session.

Deciding whether to include a safety clause in a bill is often a matter of timing. If an act is subject to the power of referendum, because it does not include a safety clause, that act cannot take effect for at least 90 days after the end of the legislative session in which it is passed. As previously explained, a citizen has 90 days after the session ends to collect enough signatures to place the act on the ballot. During that time, rather than risk implementing a law that the voters may reverse, the act is held in limbo; it cannot take effect until the time for collecting signatures expires. And if someone does collect enough signatures to put the act on the ballot, it cannot take effect until the Governor declares the vote after the next general election. General elections occur only in even-numbered years, so if an act passes in a legislative session held in an odd-numbered year and is referred to the ballot by petition, the act won’t take effect—if it even takes effect—until roughly 18 months after the end of the legislative session.