by Jery Payne

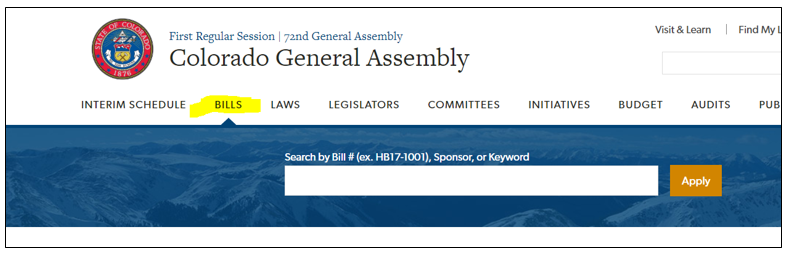

If you haven’t read the May 14th post , you will probably need to read it to make sense of this week’s post. But for a quick reminder: In the late 19th century, the Colorado Supreme Court struck down legislation that provided monetary relief for farmers because it violated section 34 of article V of the state constitution. This section prevents appropriations to persons that are not under the state’s control. In the late 20th century, the Colorado Supreme Court upheld legislation that provided monetary incentives for airlines to locate their headquarters in Colorado, even though these airlines were not under the state’s control. What changed? The Colorado Supreme Court developed the public-purpose doctrine, which we will explore this week.

In Bedford v. White, the court first articulated, in 1940, the public-purpose doctrine. The General Assembly had provided pensions for retired public servants, including judges. State Auditor Homer Bedford was concerned because pensions are appropriations for people who have retired from the state, so these people are no longer under the control of the state. Pensions appear to fall squarely within the holding of the farmer-relief case. When the two retired justices Harrison White and John Adams asked for their pensions, the state auditor refused to issue vouchers for the pension. The justices sued the state auditor. This case presented the issue of section 34’s prohibition squarely before the court.

The opinion wrestles with the fact that invalidating the pensions would really hurt the state’s ability to attract high-quality judges and employees: “[P]ensions, generally, are not considered donations or gratuities but inducements to continued service.” After all, a typical justice could probably make more income in private practice. And given that firefighters and peace officers can die in the line of duty, the state would have a harder time with recruitment unless it promised to take care of their families. Because pensions are not charity, the court didn’t believe that section 34 was really intended to forbid pensions.

The court also realized just how far reaching the holding would be: “In recent years legislation providing for pensions and retirement compensation to large numbers of persons after their retirement from service as public officers, servants, employees, and agents of the state has been enacted by the General Assembly.” And then, realizing that the opinion was going far afield from the facts presented, they made excuses for bringing it up:

The court also realized just how far reaching the holding would be: “In recent years legislation providing for pensions and retirement compensation to large numbers of persons after their retirement from service as public officers, servants, employees, and agents of the state has been enacted by the General Assembly.” And then, realizing that the opinion was going far afield from the facts presented, they made excuses for bringing it up:

We are aware of the fact that the rights of none of these classes are directly involved or may be determined in this suit. We mention them merely as instances of the possible far reaching effect of the construction of these two sections of the Constitution contended for by [the state auditor] in this case.

Yet the holding in the farmer-relief case appears to apply to pensions, which benevolently pay persons not under absolute state control. (Is the state’s control over anybody absolute?) In all this wrestling with the potential reach of section 34, the court realized that the decision in the farmer-relief case went too far.

Therefore, the court narrowed section 34 from its broad interpretation in the famer-relief case. The court held that section 34 does not prohibit appropriations that serve a public good or purpose:

If a pension has no reasonable relation to the public good it is of course a mere private grant and void. But if it serves a present public purpose it is not a mere private grant even though as an incident to the accomplishment of the public purpose the recipients thereof may be personally benefitted.

So the court upheld the pensions because they serve the public good.

During the 20th century, the Colorado Supreme Court developed the public purpose doctrine because a broad, substantive reading of section 34 is a monster that could swallow any act. Each act is passed, at least in the mind of the act’s sponsor, for benevolent purposes. (Yes, a legislator could sponsor an act for malevolent purposes, say for revenge, but how likely is that act to pass unless the sponsor can at least articulate a benevolent purpose?) The law against murder serves the benevolent purpose of protecting people. And an appropriation is required to enforce the law against murder. Therefore, the law against murder requires an appropriation that benefits the small group of people who would otherwise die and who are not controlled by the state.

Faced with this dilemma, the court developed a way to harmonize section 34 with the General Assembly’s ability to pass any appropriation: the public purpose doctrine. If the narrow reading is too narrow and the broad reading is too broad, the public purpose doctrine is the Goldilocks position; it’s a compromise. The idea is that an act is legitimate if it is for the public good rather than for private gain. The only type of act that would run afoul of this prohibition would appear to be an act that a court finds has a significant private gain with little or no public benefit. An act that has the appearance of corruption would probably fit this description, but appropriations made for a legitimate public purpose should not run afoul of section 34.