[Editor’s Note: This article has been updated as of January 3, 2019. Please click here for the updated article.]

by Richard Sweetman

No, Colorado does not have a “Stand Your Ground” law. We have a “Make My Day” law.

Wait; I’m serious. Let me explain.

“Stand Your Ground” Laws

A “Stand Your Ground” law is similar to a standard self-defense statute, in that it allows a person to use deadly force in self-defense when the person has a reasonable belief that deadly force is necessary to prevent death or serious bodily harm. However, a “Stand Your Ground” law expands upon the traditional self-defense doctrine in one or more ways. For example, a “Stand Your Ground” law may:

- Identify locations where a person may use deadly force under certain conditions, including dwellings, vehicles, businesses, and other public places where a person is legally present;

- State explicitly that a person has “no duty to retreat” before resorting to the use of deadly force in self-defense;

- Establish a presumption of reasonableness in favor of a person who uses deadly force under certain conditions;

- Establish civil immunity for a person who uses deadly force under certain conditions; or

- Allow a person to use deadly force to stop the commission of certain felonies.

Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law (Fla. Stat. 776.013), which has recently attracted much attention, reads:

(3) A person who is not engaged in an unlawful activity and who is attacked in any other place where he or she has a right to be has no duty to retreat and has the right to stand his or her ground and meet force with force, including deadly force if he or she reasonably believes it is necessary to do so to prevent death or great bodily harm to himself or herself or another or to prevent the commission of a forcible felony.

The Florida law also creates the following presumption:

(1) A person is presumed to have held a reasonable fear of imminent peril of death or great bodily harm to himself or herself or another when using defensive force that is intended or likely to cause death or great bodily harm to another if:

(a) The person against whom the defensive force was used was in the process of unlawfully and forcefully entering, or had unlawfully and forcibly entered, a dwelling, residence, or occupied vehicle, of if that person had removed or was attempting to remove another person against that person’s will from the dwelling, residence, or occupied vehicle; and

(b) The person who uses defensive force knew or had reason to believe that an lawful and forcible entry or unlawful and forcible act was occurring or had occurred.

This presumption eliminates the burden of proof for a person who used deadly force—that is, the burden to prove that he or she had a “reasonable fear of imminent peril of death or great bodily harm.” The presumption shifts the burden to the prosecution, who must prove otherwise.

Florida adopted its “Stand Your Ground” law in 2005. Since then, the number of states with similar laws has grown to 22.

Colorado’s “Make My Day” Law

Colorado adopted its “Make My Day” law in 1985. At that time, the phrase “make my day” had been popularized by the 1983 Clint Eastwood film Sudden Impact and then revived by President Reagan in his 1985 threat to veto any tax increase legislation sent to him by the U.S. Congress. In its 28-year history, Colorado’s “Make My Day” law has never been amended. The law is codified at section 18-1-704.5, C.R.S.

Colorado’s “Make My Day” law is similar to a “Stand Your Ground” law, in that both laws may be seen as expansions upon the old common law “castle doctrine.” Under this doctrine, a person has no “duty to retreat” before resorting to the use of deadly force when faced with imminent peril in his or her home. Compared to a “Stand Your Ground” law, however, Colorado’s “Make My Day” law is a relatively limited expansion.

The very idea of a statutory “castle doctrine” in Colorado is a little strange because the castle doctrine, by its own terms, is an exception to another doctrine—the duty to retreat. And except in certain specific circumstances, there has never been a duty to retreat in Colorado. (See People v. Toler, 9 P.3d 341, 348 (Colo. 2000), citing Boykin v. People, 45 P. 419 (Colo. 1896).) It is therefore no surprise that Colorado’s “Make My Day” law does not mention a duty to retreat; it has never been necessary for the General Assembly to state explicitly that no such duty exists in Colorado.

The “Make My Day” law is like the “castle doctrine” because it is limited to dwellings. Rather than stating that there is no duty to retreat in a dwelling, however, Colorado’s law lowers the standard for justifying the use of deadly force against an intruder in a dwelling.

Under Colorado’s law, any occupant of a dwelling may use deadly force against an intruder when the occupant reasonably believes the intruder (1) has committed or intends to commit a crime in the dwelling in addition to the uninvited entry and (2) might use any physical force, no matter how slight, against any occupant of the dwelling. This is a lower standard of justification than appears, for example, in Colorado’s historical self-defense statute, which is codified at section 18-1-704, C.R.S.

Colorado also has longstanding statutes justifying the use of physical force in special relationships (18-1-703, C.R.S.), in defense of premises (18-1-705, C.R.S.), and in defense of property (18-1-706, C.R.S.).

Perfectly Clear?

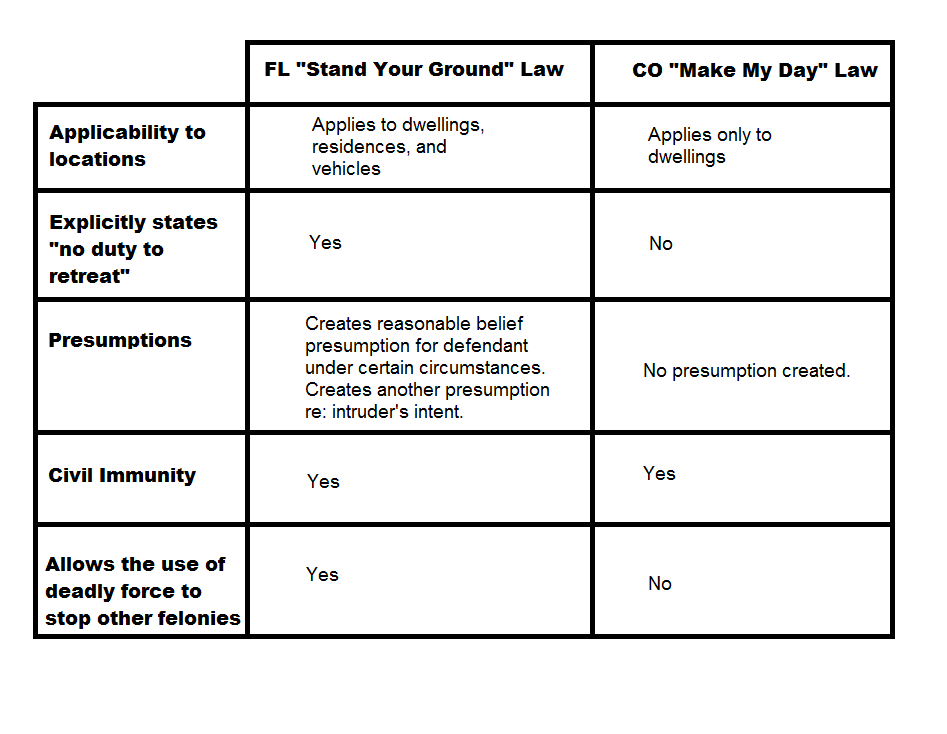

So do you now understand the difference between a “Stand Your Ground” law and Colorado’s “Make My Day” law? Not entirely? Well, that’s okay. Frankly, the distinctions are not entirely clear—partly because 22 variations of the “Stand Your Ground” law now exist. But the table below, which contrasts Florida’s law with Colorado’s law, can help you remember the key differences. For more information about “Stand Your Ground” laws, visit http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/justice/self-defense-and-stand-your-ground.aspx