by Jery Payne

Many of the residents of the town of Bow Mar were mad. They were mad at the town’s trustees, who had raised taxes to bury electric and telephone cables. To do this, the trustees had used a statute to create a special district. The citizens got lawyered up and sued the trustees. Among other claims, they argued that the special-district statute didn’t apply to the cables because the cables were owned by private, not public, companies. They got this idea from the statute’s definition of public utility:

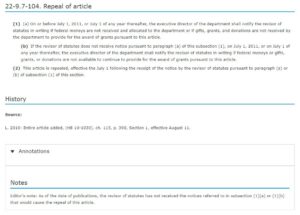

The residents argued that the phrase and shall include meant that the list, city, county, special district… was exhaustive. That is, by naming specific things the legislature meant to exclude others. A maxim of statutory interpretation is that to express one is to exclude others. So the special-district statute didn’t authorize the burial of a private corporation’s cables.

The court wasn’t persuaded. The residents appealed all the way up to the Colorado Supreme Court, who agreed with the lower court:

[T]he word include is ordinarily used as a word of extension or enlargement, and we find that it was so used in this definition. To hold otherwise here would transmogrify the word include into the word mean. [Emphasis Added]

The United States Supreme Court has also interpreted shall include. In this case, they were construing this statute:

‘[C]reditor’ shall include anyone who owns a demand or claim provable in bankruptcy, and may include his duly authorized agent, attorney, or proxy.

The court held that “It is plain that ‘shall include’ … cannot reasonably be read to be the equivalent of ‘shall mean….’”

How did these cases arise? It was because sometimes drafters need to add examples to a statute. For example, they may want a statute to apply to fruit, so they write:

Fruit means the edible part of a plant developed from a flower.

Then someone becomes concerned that a court won’t include peas or tomatoes. To address this concern, they add a comma and “including peas or tomatoes.” Yet the inclusion–exclusion maxim makes drafters fear that listing peas and tomatoes will make a court think they mean only peas and tomatoes. So they add but not limited to and end up with this: “Fruit means the edible part of a plant developed from a flower, including, but not limited to, peas and tomatoes.”

But Sutherland’s Statutes and Statutory Construction has a different take:

The word ‘includes’ is usually a term of enlargement, and not of limitation….[1]

And a review of Colorado cases suggests that the phrase “but not limited to” isn’t necessary:

- Colorado Common Cause v. Meyer: “The word ‘includes’ has been found by the overwhelming majority of jurisdictions to be a term of extension or enlargement when used in a statutory definition”

- Cherry Creek School Dist. #5 v. Voelker: “A statutory definition of a term as ‘including’ certain things does not restrict the meaning to those items included.”

- Arnold v. Colorado Dept. of Corrections: “The word ‘including’ is ordinarily used as a word of extension or enlargement and is not definitionally equivalent to the word ‘mean.’”

- DirecTV v. Crespin: “Nothing in §605(d)(6) indicates that Congress intended to depart from the normal use of “include” as introducing an illustrative—and non-exclusive—list of entities ….”

- Southern Ute Indian Tribe v. King Consol. Ditch Co: “A statutory definition of a term as ‘including’ certain things does not restrict the meaning to those items included. The word ‘include is ordinarily used as a word of extension or enlargement.”

It turns out that judges speak the same English as you and I do; they understand the meaning of includes and including.

I didn’t find any Colorado cases that went the other way. So I cast the net a little wider and found Shelby Cnty. State Bank v. Van Diest Supply Co. This case dealt with a lien on “all inventory, including, but not limited to, agricultural chemicals, fertilizers, and fertilizer materials sold to Debtor ….”[Emphasis added.] In this case the 7th circuit explained that:

[I]t would be bizarre as a commercial matter to claim a lien in everything, and then to describe in detail only a smaller part of that whole. … But if all goods of any kind are to be included, why mention only a few? A court required to give “reasonable and effective meaning to all terms” must shy away from finding that a significant phrase (like the lengthy description of chemicals and fertilizers we have here) is nothing but surplusage.

So the court did interpret the word including as limiting, and the judges didn’t care that the contract used the phrase but not limited to. So this phrase isn’t a guarantee. And I have found several similar cases, so we probably shouldn’t get much comfort from the phrase but not limited to.

Think of how many trees your Colorado could save by cutting out this unnecessary bit of legalese.

[1] N. Singer, 2A Sutherland Statutory Construction § 47.07 (Seventh Edition)