By Patti Dahlberg

America had a woman president? Many think so.

Late in September of 1919, while in Pueblo, Colorado on a cross-country public speaking tour in support of ratifying the Treaty of Versailles with its formation of a League of Nations, President Woodrow Wilson suffered a “mini-stroke.” The remainder of his train stop tour was immediately canceled, and he was rushed back to Washington, D.C. for tests and recuperation. A few days later, on October 2, the President suffered a severe stroke, which left him paralyzed on his left side, unable to speak, blind in his left eye, and only partial vision in his right eye. He was confined to bed for the next few weeks and kept away from everyone except his wife and doctor. Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, President  Wilson’s second wife, stepped in to “help him” run the government from his bedside. In the process of “protecting” her husband from unwanted stress and malicious gossip, she also excluded his staff, his Cabinet, and the Congress. Although surrounded by a “shroud of secrecy,” reports of the President’s stroke began to appear in the press in February of 1920. The extent of the President’s disability and his wife’s management of presidential affairs, however, was not fully known by the press nor shared with the nation. Several months later, the President, confined to a wheelchair, began to make public appearances again, giving an outward appearance of normalcy. Wilson did eventually walk again with the use of a cane, but many of those close to him felt he was only a shadow of his former presidential self.

Wilson’s second wife, stepped in to “help him” run the government from his bedside. In the process of “protecting” her husband from unwanted stress and malicious gossip, she also excluded his staff, his Cabinet, and the Congress. Although surrounded by a “shroud of secrecy,” reports of the President’s stroke began to appear in the press in February of 1920. The extent of the President’s disability and his wife’s management of presidential affairs, however, was not fully known by the press nor shared with the nation. Several months later, the President, confined to a wheelchair, began to make public appearances again, giving an outward appearance of normalcy. Wilson did eventually walk again with the use of a cane, but many of those close to him felt he was only a shadow of his former presidential self.

President Wilson’s health condition and probable inability to act as chief executive officer of the nation was considered by many as one of the greatest cover-ups in the history of the American presidency. During his recuperation, the First Lady would regularly review pending legislation and executive documents – becoming to some historians, the “de facto” acting president. She selected those matters that would get her husband’s personal attention and delegated the rest, without consulting him, to the members of his Cabinet to handle. Many considered her a sudden upstart, but she had been working at her husband’s side since America’s entry into World War I in April of 1917. She and the President worked together from a private, upstairs office where he gave her access to his classified document drawer and secret wartime codes. Wilson had her screen his mail and insisted she sit in on his meetings. She regularly provided him with assessments of political figures and foreign representatives and denied his advisors access to him if she determined he should not be disturbed. She was by his side in Europe as he helped negotiate the Treaty of Versailles and presented his vision of a League of Nations to prevent future world wars.

Nevertheless, the First Lady did mislead the nation by releasing carefully worded press releases that only acknowledged that the President needed rest and was working from his bedroom suite. Meanwhile, anyone wishing to confer with the President was stopped at the door by the First Lady. It was months before more than a handful of people could even testify to the President’s physical existence. Rumors flourished, questions went unanswered, and the President’s staff and cabinet were disgruntled and worried. If cabinet members or staff had papers for review, Mrs. Wilson would review the material, and only if she deemed the matter pressing would she take the paperwork to her husband for his review. Officials cooled their heels waiting in the West Sitting Room hallway until she returned with their paperwork with margin notes said to be from the President.

Edith Wilson steadfastly insisted that her husband performed all of his presidential duties after his stroke, stating in her 1938 autobiography, “My Memoir:”

Historians, however, believe that Mrs. Wilson acted as more than “steward.” They believe she was, essentially, the nation’s chief executive until her husband’s second term concluded in March of 1921.

Part of the issue preventing Congress or the Vice President from stepping in at the time was that clear constitutional guidelines did not yet exist regarding the transfer of presidential power when severe illness strikes the chief executive. Article II, Section I, Clause 6 of the U.S. Constitution regarding presidential succession states:

President Wilson was not dead nor willing to resign because of his health. Vice President Thomas Marshall refused to assume the presidency unless Congress were to declare the President incapacitated and then only if Mrs. Wilson and Dr. Grayson went along. That never happened. It would take ratification of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution in 1967 before a more specific process for the transfer of power in the event of a presidential disability became law. Some believe, because of modern medicine, that even the 25th Amendment is not clear enough regarding presidential succession and needs additional revision.

What? Did you say SIX past, present, or future presidents took part in the 1920 election?

Privately looking for an unprecedented third term, President Wilson (28th President, 1913-1921) hoped to be his party’s nominee, but party leaders were unwilling to re-nominate the ailing president still recovering from his severe stroke. Former President Theodore Roosevelt (26th President, 1901-1909), looking to be president again, was an early front-runner for his party’s nomination, but he died in 1919. With both Wilson and Roosevelt out of the running and leaving no obvious “heir apparent” for their respective parties, the Democrats and Republicans looked to lesser-known candidates.

Warren G. Harding (29th President, 1921-1923), a U.S Senator and newspaper editor from Ohio and considered a compromise candidate, won the Republican Party nomination on the tenth ballot at its national convention. Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge was chosen to be the vice-presidential candidate. When President Harding died in 1923, Calvin Coolidge succeeded to the presidency and won re-election in 1924 (30th President, 1923-1929).

James M. Cox, Governor of Ohio, won the Democrat Party’s nomination on the 44th ballot at its national convention. Future President Franklin D. Roosevelt (32nd President, 1933-1945) and Wilson supporter, was chosen to be the vice-presidential candidate.

Future President Herbert Hoover (31st President, 1929-1933) initially sought to avoid committing to any party during the 1920 election, hoping that either major party would draft him for president in their respective national convention. In March of 1920, however, he changed his strategy and declared himself to be a Republican, but it was to no avail.

Not to be left out – one presidential candidate runs his campaign from prison.

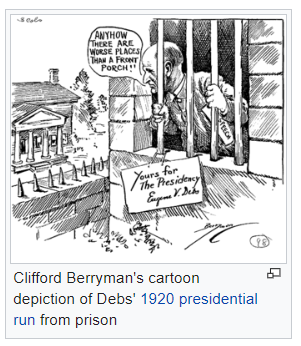

Warren G. Harding was elected to the presidency by a landslide on November 2, 1920, with 60% of the popular vote and 75% of the electoral vote. However, in that same election, socialist, political activist, labor union organizer, and former Indiana State Senator Eugene V. Debs  managed to collect more than 919,000 votes for the Socialist Party ticket, despite campaigning from the Atlanta, Georgia prison where he was serving a ten-year sentence for violating the wartime Espionage Act in 1918 by giving an antiwar speech.

managed to collect more than 919,000 votes for the Socialist Party ticket, despite campaigning from the Atlanta, Georgia prison where he was serving a ten-year sentence for violating the wartime Espionage Act in 1918 by giving an antiwar speech.

Debs ran as the Socialist candidate for president five times – 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920. President Harding, taking Debs’ deteriorating health into account, commuted his sentence in 1921. After a brief stop at the White House, Debs returned home to Terre Haute, Indiana, where he was met by band music and a crowd of 50,000. In 1924, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for his work for peace during World War I. He tried to recover his health, but died from heart failure on October 26, 1926, at the age of 70.

Resources:

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/woodrow-wilson-stroke

https://www.biography.com/news/edith-wilson-first-president-biography-facts

https://www.historynet.com/big-lie-woodrow-wilsons-sham-presidency.htm

https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1920