by Patti Dahlberg

Today the name “Colorado” runs continuously with the mighty river that originates in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains and runs south and west for 1,450 miles through Utah and Arizona and along the Nevada and California borders before heading into the Gulf of California in northwestern Mexico. But this was not the case before 1921.

For many years, various explorers wandered through the West naming landmarks as they went along. The river beginning at the Continental Divide in northwest Colorado and flowing south and west out of the state was called the Grand River. The river’s name then changed from “Grand” to “Colorado” where the Green River met it in southeastern Utah continuing on through the Grand Canyon and out to sea. Prior to being called the Grand River around 1836, portions of the river had also been known as the Rio San Rafael River, the Bunkara River, the North Fork of the Grand River, and the Blue River. The “Colorado” in the river’s name is Spanish for the “color red,” referring to the river’s muddy color flowing through the canyons in Arizona and Utah, but “Colorado” was just the final name in the long line of labels for this amazing river over the years. In the 16th century, Spanish explorers called the river Rio del Tizon, which translated to River of Embers or Firebrand River. Later, some portions of the river may have been Rio de Buena Guia, Rio Colorado de los Martyrs, Rio Grande de Buena Esperanza, Rio Grande de los Cosninos, and the El Rio de Cosminas de Rafael as explorers discovered those portions. But by the time John Wesley Powell navigated and mapped the Grand Canyon in 1869, “Colorado” was the accepted name of the river flowing through the canyon.

The Colorado River is known for its dramatic canyons and whitewater rapids, however, the river is not one single channel running from the Continental Divide, slicing through the Grand Canyon, and on to the sea. The river consists of many major tributaries merging together to form the Colorado River Basin. The Basin’s 246,000-square-mile drainage area includes parts of seven states—Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California and forms 17 miles of the international boundary between the United States and Mexico. The river supplies water to more than 40 million people and 90% of the nation’s winter vegetable production and is justifiably considered by many to be the “Lifeline of the Southwest.” Today a system of dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts control much of the Colorado and its tributaries, diverting most of its flow for agricultural irrigation and domestic water supply. The Colorado’s large flow and steep gradient is used for generating hydroelectric power, and dams regulate the water flow to meet power demands in much of the western states. Unfortunately, high water consumption has dried up the lower 100 miles (160 km) of the river, which has rarely reached the sea since the 1960s.

Continental Divide, slicing through the Grand Canyon, and on to the sea. The river consists of many major tributaries merging together to form the Colorado River Basin. The Basin’s 246,000-square-mile drainage area includes parts of seven states—Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California and forms 17 miles of the international boundary between the United States and Mexico. The river supplies water to more than 40 million people and 90% of the nation’s winter vegetable production and is justifiably considered by many to be the “Lifeline of the Southwest.” Today a system of dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts control much of the Colorado and its tributaries, diverting most of its flow for agricultural irrigation and domestic water supply. The Colorado’s large flow and steep gradient is used for generating hydroelectric power, and dams regulate the water flow to meet power demands in much of the western states. Unfortunately, high water consumption has dried up the lower 100 miles (160 km) of the river, which has rarely reached the sea since the 1960s.

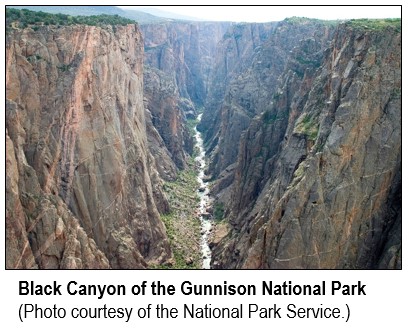

But for roughly six million years before the dams, the unfettered and free-flowing Colorado River cut deep gorges in the land, and not just through the Grand Canyon.  Along the waterways joining the Colorado —the Virgin, Kanab, Paria, Escalante, Dirty Devil, and Green rivers from the west, and the Little Colorado, San Juan, Dolores, and Gunnison from the east — many narrow, winding, deep canyons were also carved, such as Colorado’s stunning Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. Canyons cut by the rivers in Arizona and Utah include Marble Canyon, Glen Canyon, and Cataract Canyon, with the longest of these unbroken trunk canyons being the spectacular and much loved Grand Canyon. It shouldn’t be surprising that the Colorado and its tributaries flow through or near many national parks, monuments, and recreational areas.[i]

Along the waterways joining the Colorado —the Virgin, Kanab, Paria, Escalante, Dirty Devil, and Green rivers from the west, and the Little Colorado, San Juan, Dolores, and Gunnison from the east — many narrow, winding, deep canyons were also carved, such as Colorado’s stunning Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. Canyons cut by the rivers in Arizona and Utah include Marble Canyon, Glen Canyon, and Cataract Canyon, with the longest of these unbroken trunk canyons being the spectacular and much loved Grand Canyon. It shouldn’t be surprising that the Colorado and its tributaries flow through or near many national parks, monuments, and recreational areas.[i]

The Name Change

In 1921, U.S. Representative Edward T. Taylor of Colorado petitioned Congress to rename the Grand River as the Colorado River. The Glenwood Springs resident and former Colorado State Senator could not accept that the Colorado River name started in Utah and not in his beloved state. “It is absurd for one part of any stream to be given one name and the rest of the stream another name.” Congressman Taylor loved Colorado and already had a reputation for getting up on the House floor to make five to ten minute speeches about his beautiful state. He took the renaming of the Grand portion of the river as a personal mission. It was Taylor’s strong sense of state pride and historic knowledge that helped persuade Congress to change the river’s name . . . and maybe a decade of speeches and tenacity helped too.

Glenwood Springs resident and former Colorado State Senator could not accept that the Colorado River name started in Utah and not in his beloved state. “It is absurd for one part of any stream to be given one name and the rest of the stream another name.” Congressman Taylor loved Colorado and already had a reputation for getting up on the House floor to make five to ten minute speeches about his beautiful state. He took the renaming of the Grand portion of the river as a personal mission. It was Taylor’s strong sense of state pride and historic knowledge that helped persuade Congress to change the river’s name . . . and maybe a decade of speeches and tenacity helped too.

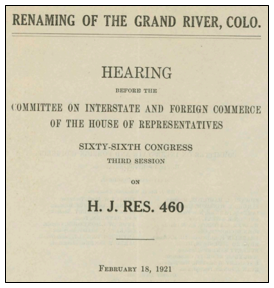

On February 18, 1921, Congressman Taylor appeared before the Congressional Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce regarding House Joint Resolution 460 “Renaming of the Grand River, Colo.” (See hearing report/transcript, H.J.R. 460 starts on page 14.) Based on his opening statement and answers to committee questions, Congressman Taylor came prepared to argue why the Colorado River name should flow continuously with the river that originates in Colorado and continues west to the sea. He provided national and regional history, local context, precedent, testimonials, statistics and measurements, and even threw in an international treaty for good measure. In his opening statement, he described the Colorado River as “the Nile of America,” and said it “is by far the most picturesque, scenic, unique, marvelous, and famous river in the world.” As for the state of Colorado, Taylor said, “… for the past 60 years, “Colorado” has meant the heart of the Golden West, the actual top of the world, the land of sunshine, good health, and gorgeous scenery, the summer playground of the Nation, the Switzerland of America, the bright jewel set in the crest of this continent, where it shines as the Kohinoor of all the gems of this Union; the sublime Centennial State.”

It did not concern Taylor that traditionally the longest tributary is regarded to be a river’s headwater or origin and the Green River—originating in Wyoming—was actually twice as long as and had a larger drainage basin than the Grand River.. Taylor backed up his claim for Colorado state superiority with volume statistics showing that the shorter Grand River (350 miles long) contributed more water to the mighty Colorado. According to information from the Colorado Historical and Natural History Society contained in the hearing report, the Grand River provided 40% of the Colorado River’s water flow, and when combined with water flow from the San Juan, Yampa, White, and other Colorado rivers, water from the state of Colorado provided closer to 60% of the river’s flow. The Natural History Society report also noted that the Green River receives more than a third of its water flow from Colorado’s Yampa and White rivers.

It did not concern Taylor that traditionally the longest tributary is regarded to be a river’s headwater or origin and the Green River—originating in Wyoming—was actually twice as long as and had a larger drainage basin than the Grand River.. Taylor backed up his claim for Colorado state superiority with volume statistics showing that the shorter Grand River (350 miles long) contributed more water to the mighty Colorado. According to information from the Colorado Historical and Natural History Society contained in the hearing report, the Grand River provided 40% of the Colorado River’s water flow, and when combined with water flow from the San Juan, Yampa, White, and other Colorado rivers, water from the state of Colorado provided closer to 60% of the river’s flow. The Natural History Society report also noted that the Green River receives more than a third of its water flow from Colorado’s Yampa and White rivers.

But Taylor may have found his most persuasive argument in the record of the U.S. Senate’s proceedings from 1861 when the Senate named the Colorado Territory. As introduced and passed by the House, the name in the bill for the proposed new territory was the “Territory of Idaho”, other names reportedly considered were Jefferson and Arcadia. In the Senate, however, the name “Idaho” was stricken and “Colorado” inserted “for the reason that the Colorado River arose in its mountains, hence there was a peculiar fitness in the name.”

Colorado’s 23rd General Assembly sent its support for renaming the Grand to the Colorado in Senate Bill 79 (later approved on March 24, 1921), the reengrossed version was included, along with various letters of endorsement, in the official Congressional Committee hearing report. After receiving support from governors and state assemblies in Colorado and Utah for the renaming of the Grand, Congress officially renamed the interstate waterway. The Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce ended its report to the House of Representatives with this statement: “There being no apparent reason sufficient in the judgment of your committee to counteract the expressed desire of the people of the State of Colorado to have this change made, your committee unanimously recommends the approval of this resolution.” On July 25, 1921, the 66th Congress passed the resolution renaming the Grand River, in spite of some lingering objections from some Wyoming and Utah representatives.

No worries, Colorado does still have its share of Grand – you only have to look around to see that. But more specifically there’s also the Grand Ditch, which pulls water from the Colorado River to the eastern slope; Grand Junction, at the confluence of the Gunnison and the then “Grand” Rivers; and, of course, Grand County.

The Colorado River Story Continues

The Colorado River may be one of the most litigated rivers in the world and, as the demand for Colorado River water continues to rise, the level of development and control of the river continues to generate controversy.

In 1922, the Colorado River Compact divided the river into the lower compact states—Arizona, California, and Nevada—and the upper compact states—Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. It was the first time more than three states negotiated an agreement among themselves to allocate the waters of a river. At that time the total annual flow of the Colorado River was estimated to be close to 16.5 million acre-feet ( an “acre foot” is the amount of water required to cover one acre to a depth of one foot) at Lees Ferry, AZ., of which 15 million acre-feet were divided between the lower and the upper compact states. A treaty in 1944 allocated 1.5 million acre-feet of water per year to Mexico. It was later realized that the initial estimate of Colorado River water volume in the 1922 compact was based upon an abnormally wet period and that substantially less water was available than the amounts specified in the agreements. In 2019, after several years of negotiations and in response to ongoing drought conditions and the increased potential for water supply issues, the upper and lower basins began implementing drought contingency plans to manage water demand.

Sources:

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Colorado-River-United-States-Mexico

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorado_River

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/americannile/

- https://www.kpbs.org/news/2018/mar/27/how-colorado-river-got-its-name/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_T._Taylor

- https://www.watereducation.org/aquapedia-background/colorado-river-compact

- https://www.americanrivers.org/river/colorado-river/

- https://www.watereducationcolorado.org/fresh-water-news/as-2020-kicks-in-historic-colorado-river-drought-plan-gets-first-tests/

- https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45546

[i] National monuments, parks, and recreation areas located in the Colorado River Basin:

- Arches National Park

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

- Bryce Canyon National Park

- Curecanti National Recreational Area

- Canyonlands National Park

- Dinosaur National Monument

- Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

- Grand Canyon National Park

- Lake Mead National Recreational Area

- Natural Bridges National Monument

- Rocky Mountain National Park

- Zion National Park