by Patti Dahlberg

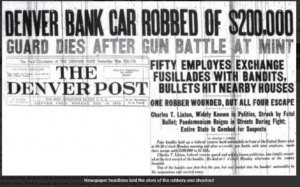

DENVER, Dec. 18, 1922 – As a Federal Reserve Bank truck sat outside the U.S. Mint in Denver to pick up a weekly cash shipment for transport to various area banks, a black Buick touring car with drawn curtains slowly pulled up beside it. According to witnesses, three or four masked men jumped out of the car while one remained behind the wheel. One of the masked men ran to the rear of the reserve truck, yelled at the guards, fired at and fatally wounded the guard at the back of the truck, and shot out the back doors and windows of the truck. One man quickly lifted bags of money out of the truck and threw them into the Buick while the other masked men sprayed the Mint building exits and windows with bullets from sawed-off shotguns. Alarm bells clanged and Mint guards and employees grabbed rifles and began firing out windows and doors.

guards, fired at and fatally wounded the guard at the back of the truck, and shot out the back doors and windows of the truck. One man quickly lifted bags of money out of the truck and threw them into the Buick while the other masked men sprayed the Mint building exits and windows with bullets from sawed-off shotguns. Alarm bells clanged and Mint guards and employees grabbed rifles and began firing out windows and doors.

Within seconds, bullets were peppering West Colfax Avenue, hitting the side of the Mint building and several other nearby buildings. According to the Dec. 19, 1922, New York Times:

So terrific was the gunfire that forty bullet holes can be counted in the transoms above the main entrance to the mint and in the windows of the second story. Bullets riddled windows in various stores and apartment houses across the street and there were many narrow escapes from bullets. One shot went through a window in Sylvania Hotel, at Court Place and West Colfax Avenue, and shattered a picture on the wall.

The shootout lasted only about ninety seconds before the getaway driver took off, ran another vehicle into a fire hydrant (adding to the confusion and mayhem), and sped away east on Colfax Avenue with an estimated $200,000 in $5 bills. Witnesses reported that while fleeing the scene, one of the bank robbers stood on the car’s running board[1], presumably to fire back at the Mint guards, but was instead shot and seriously wounded before being pulled back into the car.

The entire event was over in five minutes. Charles T. Linton, who died in the shootout, is the only Federal Reserve guard to lose his life during a bank robbery. Hailed by many as the “wildest gun battle in Denver history,” the robbery was also reported by the Cheyenne Wells Record  (December 21, 1922) to be the first successful Mint holdup in U.S. history and the largest robbery in Denver.

(December 21, 1922) to be the first successful Mint holdup in U.S. history and the largest robbery in Denver.

In the aftermath of the robbery, witnesses came forward to help investigators with descriptions and drawings of the thieves and the number of robbers involved went from four to seven. Roads in and out of Denver were shut down and according to the New York Times: “Tonight every highway in the State is guarded and police and Federal authorities have armed squads out in pursuit of an automobile occupied by seven men who were seen speeding northward soon after the robbery. One of the occupants was bleeding profusely, having been wounded in the jaw by one of the mint guards, it is believed.”

In the ensuing investigation, the robbers were tracked from Omaha to Chicago, then to St. Paul, before the trail went cold. Then on January 14, 1923, investigators discovered the getaway car in an old garage on Gilpin Street in Denver. Inside the car was a frozen body identified through fingerprints as Nicholas “Chaw Jimmie” Trainor, a.k.a. James Sloan. It was determined that Trainor had been mortally wounded during the robbery and his body left behind as the rest of the gang escaped. Once Trainor was identified, police suspected that Harvey Bailey, a known associate of Trainor’s, was likely to have been involved in the robbery. In spite of offering rewards of more than $10,000, none of the other robbers were positively identified. The discovery of the getaway car led investigators to other leads in the case including a trunk filled with firearms, ammunition, photographs, and letters.

Secret Service agents recovered about $80,000 of the stolen mint money in a Minnesota hideout, along with $73,000 in negotiable bonds from an Ohio robbery. Since Trainor and Bailey were both considered suspects in that Ohio heist, which predated the Denver robbery, police became further convinced of Bailey’s involvement in the Mint robbery. According to the police, the thieves fled to the Minneapolis-St. Paul area with the money, which was given to a “prominent Minneapolis attorney.” Bailey fell off police radar in late 1922 and continued evading capture until his eventual arrest and conviction in 1933. He later died in 1979.

In 1934, twelve years after the robbery, the remaining robbers were identified. The Denver Police Chief at the time, Albert T. Clark, released a statement announcing that five men, as well as two women, had colluded in the robbery. According to an article printed in California’s Healdsburg Tribune, Clark also disclosed that, of the individuals involved, only two remained alive, and both were serving life sentences for other crimes. The police added that the other members of the gang had died violently. According to the police, Harvey Bailey had driven the car and was serving a life-sentence in Alcatraz for the kidnapping of an Oklahoma City millionaire. James Clark was serving a life-sentence in the Indiana State Penitentiary for bank robbery. Other gang members, Harold Burns and Frank McFarland “The Memphis Kid” were dead. Nicholas Trainor/James Sloan had been found dead in the getaway car shortly after the robbery and the bullet-riddled body of his common-law wife, Florence Thompson, was found in 1927. Harold Burns’ wife, Margaret, was found shot and burned in 1932. The case of the Denver Mint robbery was considered closed without a single person ever charged in connection with the theft.

Two earlier attempts to rob the Denver Mint fail

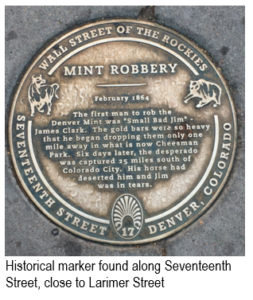

The first attempt to rob the Denver Mint was a year or so after the Mint was established, when James D. Clark, a.k.a. Small Bad Jim, landed a job at the Mint. He kept it simple – stuff your pockets with as much as you can and get out of town fast. In February of 1864, he left work with $37,000 in gold and treasury notes. Reportedly, the gold bars were so heavy he started dropping them in the Cheesman Park area on his way out of town. When he was captured, officials recovered about $32,000, the remainder remained missing. After his arrest, Clark escaped from jail but was eventually rearrested, tried for his crime, and banished from the territory.

with $37,000 in gold and treasury notes. Reportedly, the gold bars were so heavy he started dropping them in the Cheesman Park area on his way out of town. When he was captured, officials recovered about $32,000, the remainder remained missing. After his arrest, Clark escaped from jail but was eventually rearrested, tried for his crime, and banished from the territory.

The next attempt was in 1920 when Orville Harrington, also a Mint employee, attempted to steal gold bars by wrapping them in newspaper and stuffing them into the hollow shank of his wooden leg. He successfully smuggled out 40 gold bars, worth about $81,000, to his house and buried them in his yard. He was caught when a fellow employee witnessed him putting gold bars in his wooden leg. He was tried for his crime and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

But before there was a Denver Mint —

Printing your own money – the early days of the Colorado Frontier

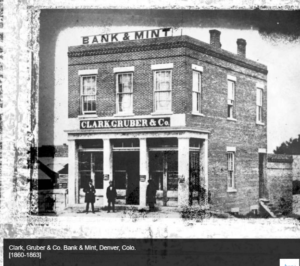

Founded in July 1860 by Austin M. Clark, Milton E. Clark, and E.H. Gruber, the Clark, Gruber & Co. Bank and Mint was located on the corner of 16th and Market, and served several functions,  including bank, assayer’s office, and money factory. At the time, Denver was teeming with precious metals mined in the mountains and extracted in frontier smelting plants. While plenty of local businesses used bags of gold dust for currency, the demand for cash and coins remained high. Clark and Gruber’s private bank and mint gave prospectors a place to safely deposit their earnings and turn their precious metals into currency. The enterprise, which was legal, served an important role in keeping cash flowing on the streets of Denver and helped establish financial norms and standards within the community.

including bank, assayer’s office, and money factory. At the time, Denver was teeming with precious metals mined in the mountains and extracted in frontier smelting plants. While plenty of local businesses used bags of gold dust for currency, the demand for cash and coins remained high. Clark and Gruber’s private bank and mint gave prospectors a place to safely deposit their earnings and turn their precious metals into currency. The enterprise, which was legal, served an important role in keeping cash flowing on the streets of Denver and helped establish financial norms and standards within the community.

Clark and Gruber’s operation proved to be very popular, generating more than $3 million worth of business in their first two years. A $10 gold piece from Clark and Gruber’s was regarded as a reliable form of currency that could be used locally and transported to other parts of the country without losing value.

In 1862, Congress passed a bill that allowed the government to purchase Clark and Gruber’s operation and turn it into an official U.S. Mint, and in 1864, Congress passed a law banning private mints, ending the era of frontier money.

________________________________________________________

[1] A long, narrow board that is attached to the side of a vehicle to make it easier for people to get in and out.

Sources:

- https://www.lawweekcolorado.com/article/the-wildest-gun-battle-in-denver-history-was-also-the-first-successful-mint-holdup-in-the-u-s/

- http://www.colfaxavenue.org/2017/04/denver-mint-holdup-wildest-gun-battle.html

- https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=HT19341203.2.13&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–1

- https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/denver-mint

- http://coloradorestlessnative.blogspot.com/2011/04/one-never-knows-when-bullets-will-fly.html

- https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/print-your-own-money-story-first-denver-mint

- https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=100808

- https://m.facebook.com/denverpolice/posts/throwback-thursday-that-time-the-mint-was-robbedwhen-people-think-of-the-first-t/763584167079902/