by Frank Stoner

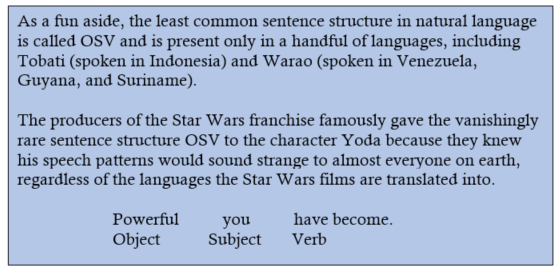

Despite the fact that there are only 10 ways to write a sentence, there remain infinitely many possible sentence constructions. English, like German, Mandarin, and Russian, is what linguists call an SVO language. That is to say, English writers will typically first tell you the [S]ubject, then the [V]erb, and then the [O]bject.

For example:

She loves him.

Subject Verb Object

In what linguists call SOV languages, like Japanese or Latin, a writer will first tell you the [S]ubject, then the [O]bject, and then, finally, the [V]erb. An equivalent Latin sentence rendered in English would look like this:

She him loves.

Subject Object Verb

Almost 90% of the world’s 6,000 or so languages use one of these two sentence structures.

This very basic architecture seems to suggest that each language has only one sentence structure and that all natural languages (that is to say, natural human languages; not codes or computer languages) only ever include subjects, verbs, and objects, just in different orders. So, you might be wondering, Why does the title say there are 10 ways to write a sentence?

Although it is true that English only uses the SVO sentence structure, there are 10 sentence patterns that employ the structure in different ways—mainly dealing with the “V” and “O” parts: the verbs and the objects.1 Among those different ways are four categories of things a sentence can do. These categories are organized below according to the traditional Reed-Kellogg model, which—in theory—places the sentence patterns in ascending of order of verb complexity.2

things a sentence can do. These categories are organized below according to the traditional Reed-Kellogg model, which—in theory—places the sentence patterns in ascending of order of verb complexity.2

Category A. A sentence can tell us what something is.

This category, often called the “be patterns,” always includes some form of the verb “to be” (am, are, is, was, were, etc.) as its “predicating” or main verb. This category of sentence patterns is perhaps the most frequently used set in legal writing because its patterns always tell us something about the constitution of the subject. There are three patterns:

(I). The chambers are upstairs. (upstairs gives us information of time or place about the subject).

(II). The members are diligent. (diligent describes the subject).

(III). Senator Smith is my representative. (my representative renames or defines the subject).

Category B. A sentence can tell us what something is like.

This category, often called the “linking verb patterns,” tells us something about the subject with any verb except a “be-verb.” There are two patterns:

(IV). The members seem busy. (seem busy tells us information about the members without defining them).

(V). The members remained citizens. (remained “links” the object citizens to the subject members without defining them with a “be-verb”).

Category C. A sentence can tell us what something does.

This category consists of only one pattern—an intransitive sentence. An intransitive sentence is, essentially, just the SV part of the larger SVO structure—in other words, no object follows the verb.

(VI). The General Assembly adjourned. (nothing follows the verb adjourned).

Category D. A sentence can tell us what something does to something else.

This category consists of the four transitive patterns, and is perhaps the second-most commonly used structure in legal writing—though it is perhaps the most common structure in everyday speech.

(VII). The legislature passed the bill. (the bill here is what linguists call a direct object, since it is the “thing” acted upon by the subject).

(VIII). The editor gave the clerk the amendment. (the clerk here is what linguists call an indirect object since it is involved indirectly with the main object being acted upon: the amendment).

(IX). The members consider the chairperson intelligent. (intelligent describes the indirect object chairperson without renaming or defining it).

(X). The members elected Senator Smith chairperson. (chairperson renames or defines the indirect object Senator Smith).

You may have a suspicion that these 10 patterns don’t cover quite everything that English speakers can write. What about adverbs, you might ask? First of all, words or phrases that “fancy up” a sentence are not considered vital to a sentence’s structure because the SVO structure can function without such niceties. Adverbs, for instance, can be moved anywhere within a sentence and therefore do not constitute any additional patterns:

Quickly, they ran up to the chamber.

They ran quickly up to the chamber.

They ran up to the chamber quickly.

Prepositional phrases like up to the chamber and other kinds of phrases that serve to “fancy up” a sentence are also not considered essential to a sentence’s function. While those kinds of phrases may carry essential meaning, they do not perform an essential function of an SVO sentence. For that reason, they do not constitute any patterns additional to the 10 listed above in Roman numerals.

The final, and perhaps most important thing that allows English speakers to do so much with just 10 basic sentence patterns is what linguists call “recursion.” Using a process called nominalization (you can think of this as meaning “nounify”), speakers can take any of the 10 patterns and embed them in any place a noun (that is, a subject, object, indirect object, or direct object) normally belongs. Consider the following:

Witches are scary.

Subject Verb Object

(Pattern II sentence)

________________________

Dorothy thinks witches are scary.

Subject Verb Object

(Pattern II sentence embedded in a pattern VII sentence)

Here, the full sentence “Witches are scary” can be nominalized into a single object and embedded as a chunk within another complete sentence: “Dorothy thinks witches are scary.” This remarkable feature of both the human mind and language allows any of the 10 sentence patterns to be combined, reshaped, planted, or otherwise embedded within any other sentence. Given the 170,000 or so words English has within its lexicon, 10 patterns—and the ability to use them recursively—really are enough to say infinitely many things.

1. These are the 10 sentence patterns according to the Reed-Kellogg model, discussed in Martha Kolln’s and Robert Funk’s “Understanding English Grammar” (Longman, 2012).

2. The Reed Kellogg model, a 19th century creation, has largely fallen out of favor with contemporary linguists, but the model is still taught by English instructors who believe pictorial sentence diagrams are valuable to help students visualize sentence structure.