The 2026 legislative session will convene at 10 a.m. on Wednesday, January 14, but, as those of us who follow the legislature know—particularly OLLS drafting attorneys—bill drafting starts long before that date. In fact, legislators have been submitting bill requests for the upcoming session since the end of the last session. (Thank you, early birds!)

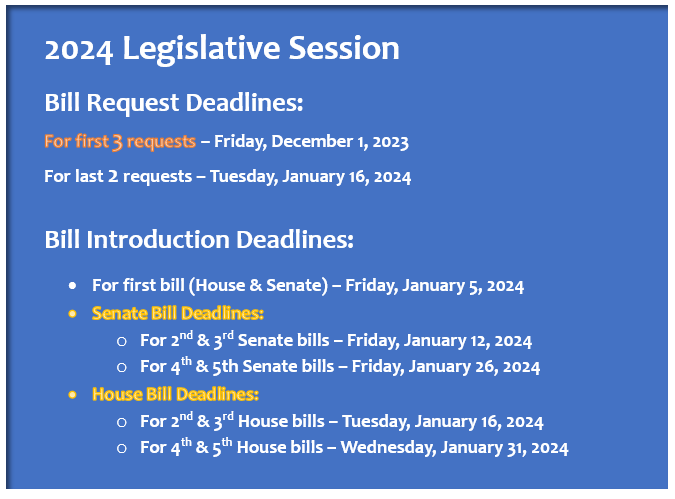

Life outside the Capitol can get very busy – especially when there is a special session like we had in August – making it easy to forget that the first bill request deadline for legislators is December 1. This first deadline is for a legislator’s first three bill requests. After December 1, a legislator may submit up to two additional bill requests, for a total of five bill requests allowed by rule per legislator per session.*

Once a legislator has submitted bill requests to the OLLS, the legislator must choose one of those requests to be a “prefile” bill. The designated prefile bill must be drafted, edited, revised, finalized, and filed with the House or the Senate several days before the January convening date. Generally, the bill deadlines require legislators to have completed, with the help of OLLS drafters, the bulk of their bill drafting well before the first day of the legislative session.

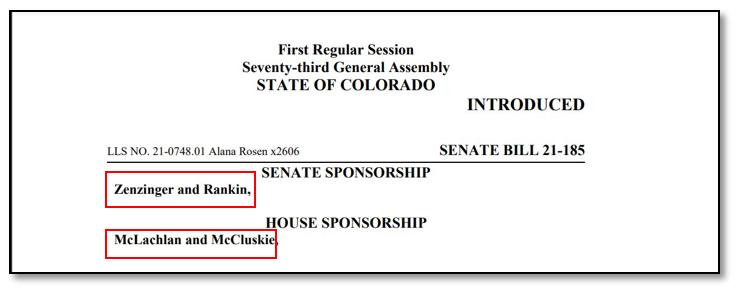

What legislators need to know about requesting bills [Joint Rule 24 (b)(1)(A)]:

- The Joint Rules allow each legislator five bill requests each session. These five bill requests are in addition to any appropriations, committee-approved, or sunset bill requests that a legislator may choose to carry. (Legislators are not required to carry five bills.)

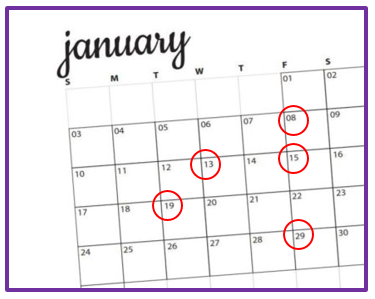

- To reach the five-bill request limit within the bill request deadlines, legislators must submit at least three bill requests to OLLS by the early request deadline (December 1). Then legislators must submit the remaining two requests (assuming the legislator is under the five-request limit), by the seventh legislative day. For the 2026 legislative session, this deadline is January 20.

- If a legislator submits fewer than three requests on or before the early bill request deadline, the legislator forfeits the remaining of those three bill requests due by that date, but the legislator may still request two additional bills by the January 20 deadline.* (Legislators are not required to carry five bills.)

- The first bill request deadline is still a couple of months away, but OLLS recommends legislators work with drafters well ahead of the December 1 deadline on the first three bill requests. (Hint hint!) The legislator will also need to quickly decide which of these requests will become a “prefile” bill, which needs to be filed for introduction prior to the first day of the legislative session. For the 2026 legislative session, the deadline to file prefile bills with the House and Senate is Friday, January 9.

Legislators can submit bill requests to OLLS by phone, email, or in person. (We like it when you stop by! Note, however, that we are all working remotely until we can move into our new location on the third floor of the Annex Building, so please wait to stop by in person until after we move into the Annex in late October.) Including as much drafting information as possible and the names of any contacts with drafting authority helps bill drafters start work on the bill request right away.

Legislators: If you have not yet submitted a bill request, you are encouraged to do so as soon as possible. Bill requests may address any subject and do not need to be completely conceptualized. The assigned bill drafter will help you with the wording of your bill, and the bill drafting process allows for potential issues or problems to rise to the surface and make it easier for you to decide whether the idea is “workable.” If a request is no longer needed or wanted, you can withdraw and replace it with a new request, as long as that decision is communicated to the bill drafter before the December 1 bill request deadline. By submitting bill requests and draft information as quickly as possible, legislators give OLLS drafters and editors more time to work on the drafts and make it easier to determine if there are duplicate bill requests and work out any drafting kinks before the first day of session.

Legislators can submit more than three requests before the early bill request deadline. If a legislator submits three requests by December 1 and later withdraws one of them, the legislator forfeits the withdrawn bill request because the rules allow a legislator to submit only two bill requests after the December deadline.* If a legislator submits four bill requests by the early bill request deadline and later withdraws one, the legislator is left with three bill requests that met the early request deadline. That legislator can still submit the two requests that are allowed after the early bill request deadline—for a total of five bill requests.

Upcoming deadlines: Too many to remember and too important to forget! Click here for the 2026 deadline schedule.

But for now, remember these 2026 bill request deadlines:

- Monday, December 1, 2025. The last day for legislators to request their first three (or early) bill requests. After this date, legislators are only allowed two additional bill requests, with a limit of up to five bill requests total.

- Tuesday, January 20, 2026. The last day for legislators to request their final two (or regular) bill requests. (This applies only to legislators who have not yet requested all five of their allowed bills.)

Good luck, legislators, and please don’t hesitate to reach out to OLLS with any questions!

* A legislator may seek permission from the House or Senate Committee on Delayed Bills, whichever is appropriate, to submit additional bill requests or to waive a bill request deadline.