The Office of Legislative Legal Services will be working remotely from September 18 through mid-October as the office moves from the Colorado State Capitol to the State Capitol Annex Building. If you need to contact OLLS staff, please feel welcome to reach out to the OLLS Front Office at (303) 866-2045 or olls.ga@coleg.gov. See you in our new office space soon!

Category: Miscellaneous

-

LegiSource is on Hiatus

The Colorado LegiSource is taking a break for the next several weeks. We expect to resume postings in September. In the meantime, if you have questions you would like answered or issues you would like to see discussed, please contact us at feedback@legisource.net.

-

AI is Coming to a Legislature Near You

by Jessica Chapman

Can you believe Siri is a teenager? The digital assistant first became available as an iOS app in 2010. Amazon’s Alexa started interrupting living room and kitchen conversations not long after in 2014. These technologies exposed many people to artificial intelligence for the first time.

These days, “AI” seems to touch every part of our lives in some way or another. We’re exposed to it daily in online customer service, map applications, weather forecasting, email reminders, and autocomplete functions (when texting for example). AI-enhanced robots clean airplanes now. AI Note Takers join our meetings. We have self-driving cars!

And while AI certainly predates Siri’s arrival, the decade and a half since her appearance on iPhones has hosted a genuine groundswell of innovation in, attention to, and curiosity (plus anxiety) about artificial intelligence that continues to build to this day.

In tandem with these technological advances, state legislatures including our own have been working to wrap their arms around artificial intelligence from a policy perspective. It’s an ongoing and unfolding situation complicated by the fact that states and municipalities are considering bills and passing (or vetoing in some cases) laws pretty much every week.

In 2024 alone, 31 states – including Colorado – adopted resolutions or enacted legislation to study AI. HB 24-1468 created Colorado’s Artificial Intelligence Impact Task Force consisting of a bipartisan membership of 26 legislators and industry and public interest experts and professionals.

At the task force’s October meeting, a presenter from TechNet, a bipartisan network of technology executives, shared that 17 bills related to artificial intelligence had passed in California since the previous task force meeting just over a month earlier. Just in California!

The National Conference of State Legislatures has been working to keep up too. The organization only began specifically tracking artificial intelligence legislation in 2019. Its task force on cybersecurity and privacy reorganized and expanded in 2023 due to what NCSL’s executive committee saw as the growing importance of AI.

The leaps and bounds in interest in artificial intelligence among state legislatures show up in the numbers. NCSL records indicate there were about 125 measures involving artificial intelligence introduced across the United States and its territories in 2023. In 2024, that number more than doubled to over 300.

(These numbers pertain to AI generally and don’t include legislation related to specific AI technologies like facial recognition, deepfakes, and self-driving cars. NCSL tracks those issues separately.)

“There is a swelling interest from the states because of a lack of federal action,” says Chelsea Canada, program principal of NCSL’s Financial Services, Technology and Communications Program. “It’s been a flurry of activity that continues to increase.”

In addition to HB24-1468, Colorado passed two other bills related to AI during the 2024 session: One related to the use of deepfakes in elections (HB 24-1147) and one that creates a regulatory structure for artificial intelligence (SB 24-205).

SB 24-205, commonly referred to as the Colorado Artificial Intelligence Act, or CAIA, has generated discussion and comment from the task force and news sources for being among the first legislation of its kind in the United States to regulate what it terms “high-risk” artificial intelligence systems. (Utah passed the Utah Artificial Intelligence Policy Act in March.)

“High-risk,” according to the Colorado’s CAIA, means AI systems that make or are a substantial factor in making a “consequential” decision.

CAIA offers Colorado consumers recourse to address what it describes as “algorithmic discrimination” which can occur when high-risk AI plays a role in hiring practices, housing and loan applications, and other consumer services.

Tech giants including Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and IBM have appeared before the state’s task force to weigh in on provisions of the SB 24-205, which does not go into effect until February 1, 2026.

So far in the 2025 session, there are two bills related to AI under consideration by Colorado’s general assembly – SB 25-022, which contemplates the use of AI to fight wildfires, and HB 25-1212, which would create certain whistleblower protections for employees of artificial intelligence developers.

According to the NCSL’s Chelsea Canada, states have been looking to the federal government and elsewhere for guidance on how to approach AI regulation, as there is not yet a consensus even on the definition of artificial intelligence. The relative immaturity of the industry poses challenges since AI technologies operate across state and national borders.

Plenty of parties are eager to plant their flags though.

The White House issued an executive order in October 2023 laying out principles for “safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence.” The federal government followed up on that order in October 2024 with additional AI guidance aimed specifically at United States military and intelligence agencies.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has also taken a stab. In mid-February, France hosted the third annual Artificial Intelligence Action Summit convening over 1,000 participants representing over 100 countries.

Trade organizations are getting in on the game too.

The American Bar Association issued a formal opinion in July 2024 on how lawyers should approach the use of AI. Industry insiders are closely following lawsuits working their way through the court system for direction on how to handle artificial intelligence.

A quick search reveals lawsuits that make accusations of price-fixing, health care denials, and even, sadly, wrongful death at the hand of artificial intelligence. How these cases resolve could influence future legislation.

We at the Office of Legislative Legal Services have been evaluating if and how to permit artificial intelligence into drafting and editing operations as well. The office convened a task force during the 2024 interim to survey our 60-plus employees on our awareness of and familiarity with AI tools.

As a result of its efforts, OLLS now has an in-house policy on the use of AI, which dictates that “OLLS employees shall not upload, enter, or otherwise incorporate confidential information into GAI [generative AI] or instruct GAI to generate confidential information.” Generative AI is a type of AI – the most well-known example is ChatGPT – that creates new content based on user inputs.

“We’re interested in exploring how AI technology can be used to improve our work product and enhance the service that we provide to the members of the General Assembly,” says Director Ed DeCecco. “But the use of AI must also be consistent with our statutory and ethical obligations of confidentiality. With that perspective, we are continuing to review how and if AI can be effectively used in our work.”

Stay tuned, and welcome to the Wild West of AI!

Says NCSL’s Chelsea Canada, “It’s an area that is emerging and evolving, and the interest is expanding and the work is increasing because members are more and more interested.”

Artwork generated by magicstudio.com (a generative AI tool) in response to the prompt “artificial intelligence in the legislative environment.”

-

There Are Only 10 Ways to Write a Sentence

by Frank Stoner

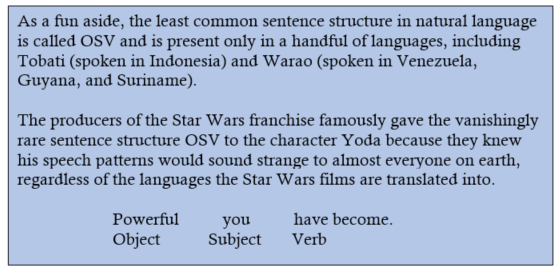

Despite the fact that there are only 10 ways to write a sentence, there remain infinitely many possible sentence constructions. English, like German, Mandarin, and Russian, is what linguists call an SVO language. That is to say, English writers will typically first tell you the [S]ubject, then the [V]erb, and then the [O]bject.

For example:

She loves him.

Subject Verb Object

In what linguists call SOV languages, like Japanese or Latin, a writer will first tell you the [S]ubject, then the [O]bject, and then, finally, the [V]erb. An equivalent Latin sentence rendered in English would look like this:

She him loves.

Subject Object Verb

Almost 90% of the world’s 6,000 or so languages use one of these two sentence structures.

This very basic architecture seems to suggest that each language has only one sentence structure and that all natural languages (that is to say, natural human languages; not codes or computer languages) only ever include subjects, verbs, and objects, just in different orders. So, you might be wondering, Why does the title say there are 10 ways to write a sentence?

Although it is true that English only uses the SVO sentence structure, there are 10 sentence patterns that employ the structure in different ways—mainly dealing with the “V” and “O” parts: the verbs and the objects.1 Among those different ways are four categories of

things a sentence can do. These categories are organized below according to the traditional Reed-Kellogg model, which—in theory—places the sentence patterns in ascending of order of verb complexity.2

things a sentence can do. These categories are organized below according to the traditional Reed-Kellogg model, which—in theory—places the sentence patterns in ascending of order of verb complexity.2Category A. A sentence can tell us what something is.

This category, often called the “be patterns,” always includes some form of the verb “to be” (am, are, is, was, were, etc.) as its “predicating” or main verb. This category of sentence patterns is perhaps the most frequently used set in legal writing because its patterns always tell us something about the constitution of the subject. There are three patterns:

(I). The chambers are upstairs. (upstairs gives us information of time or place about the subject).

(II). The members are diligent. (diligent describes the subject).

(III). Senator Smith is my representative. (my representative renames or defines the subject).

Category B. A sentence can tell us what something is like.

This category, often called the “linking verb patterns,” tells us something about the subject with any verb except a “be-verb.” There are two patterns:

(IV). The members seem busy. (seem busy tells us information about the members without defining them).

(V). The members remained citizens. (remained “links” the object citizens to the subject members without defining them with a “be-verb”).

Category C. A sentence can tell us what something does.

This category consists of only one pattern—an intransitive sentence. An intransitive sentence is, essentially, just the SV part of the larger SVO structure—in other words, no object follows the verb.

(VI). The General Assembly adjourned. (nothing follows the verb adjourned).

Category D. A sentence can tell us what something does to something else.

This category consists of the four transitive patterns, and is perhaps the second-most commonly used structure in legal writing—though it is perhaps the most common structure in everyday speech.

(VII). The legislature passed the bill. (the bill here is what linguists call a direct object, since it is the “thing” acted upon by the subject).

(VIII). The editor gave the clerk the amendment. (the clerk here is what linguists call an indirect object since it is involved indirectly with the main object being acted upon: the amendment).

(IX). The members consider the chairperson intelligent. (intelligent describes the indirect object chairperson without renaming or defining it).

(X). The members elected Senator Smith chairperson. (chairperson renames or defines the indirect object Senator Smith).

You may have a suspicion that these 10 patterns don’t cover quite everything that English speakers can write. What about adverbs, you might ask? First of all, words or phrases that “fancy up” a sentence are not considered vital to a sentence’s structure because the SVO structure can function without such niceties. Adverbs, for instance, can be moved anywhere within a sentence and therefore do not constitute any additional patterns:

Quickly, they ran up to the chamber.

They ran quickly up to the chamber.

They ran up to the chamber quickly.

Prepositional phrases like up to the chamber and other kinds of phrases that serve to “fancy up” a sentence are also not considered essential to a sentence’s function. While those kinds of phrases may carry essential meaning, they do not perform an essential function of an SVO sentence. For that reason, they do not constitute any patterns additional to the 10 listed above in Roman numerals.

The final, and perhaps most important thing that allows English speakers to do so much with just 10 basic sentence patterns is what linguists call “recursion.” Using a process called nominalization (you can think of this as meaning “nounify”), speakers can take any of the 10 patterns and embed them in any place a noun (that is, a subject, object, indirect object, or direct object) normally belongs. Consider the following:

Witches are scary.

Subject Verb Object

(Pattern II sentence)

________________________

Dorothy thinks witches are scary.

Subject Verb Object

(Pattern II sentence embedded in a pattern VII sentence)

Here, the full sentence “Witches are scary” can be nominalized into a single object and embedded as a chunk within another complete sentence: “Dorothy thinks witches are scary.” This remarkable feature of both the human mind and language allows any of the 10 sentence patterns to be combined, reshaped, planted, or otherwise embedded within any other sentence. Given the 170,000 or so words English has within its lexicon, 10 patterns—and the ability to use them recursively—really are enough to say infinitely many things.

1. These are the 10 sentence patterns according to the Reed-Kellogg model, discussed in Martha Kolln’s and Robert Funk’s “Understanding English Grammar” (Longman, 2012).

2. The Reed Kellogg model, a 19th century creation, has largely fallen out of favor with contemporary linguists, but the model is still taught by English instructors who believe pictorial sentence diagrams are valuable to help students visualize sentence structure.

-

A Journey of 14,000 Feet Begins With a Single Step, or “How to (Re)Name a Colorado Mountain”

by Conrad Imel

In 1861, when botanist Dr. Charles C. Parry was on his first botanical exploration of the Rocky Mountain region in Colorado, two tall mountain peaks attracted the doctor’s attention. Following the practice among botanists to name new plants after each other, Dr. Parry named the peaks after two of his colleagues, Asa Gray and John Torrey. Today, Grays Peak and Torreys Peak, the two “14ers” that sit just west of Denver, are popular with hikers, in part because their proximity allows a hiker to summit both in one day. If you (or anyone in

OLLS… hint, hint) wanted to name a mountain after a colleague, how would you go about it? The answer is a little fuzzy, but let’s see if LegiSource can help make sense of it.

OLLS… hint, hint) wanted to name a mountain after a colleague, how would you go about it? The answer is a little fuzzy, but let’s see if LegiSource can help make sense of it.Neither the state nor the federal government has the exclusive authority to name a mountain, so the General Assembly could take steps to rename a mountain for state purposes. But it’s likely the best approach is to work through the federal board responsible for naming geographic features for federal purposes. The names bestowed by the federal board are used on federal maps and often followed by state and local governments.

Federal renaming process

Geographic names, including names of mountains, specifically established by federal law or executive order are official for federal purposes and can only be changed by federal law or subsequent order. But many federally recognized geographic names aren’t established by Congress or the President, they are approved by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN). Congress established the current BGN in 1947 to promote uniformity within the federal government in naming geographic features. The BGN’s decisions only apply to the federal government; state and local governments generally use the federal names, but there is no law requiring them to do so.

The BGN does not create names for geographic features; it approves or rejects names proposed by others, based on the BGN’s principles, policies, and procedures. For domestic names, anyone can suggest a name for approval by submitting a proposal online or printing and completing a Domestic Geographic Name Proposal form. After receiving a suggestion, the BGN will conduct an investigation to ensure the suggestion conforms to BGN policies. It will also receive input from the general public; state naming authorities; interested federal, state, and local agencies; and federally recognized Indian tribes.

You probably haven’t noticed any changes to the names of Colorado landmarks lately, and there’s a reason for that. As part of the name change process, the BGN works with the state naming authority in the state where the geographic feature resides. Colorado’s state naming authority was disbanded in 2013, so the BGN ceased working on name changes for features within the state. But fear not, on July 2, 2020, Governor Polis established a new Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board that will work with the BGN. BGN staff has met with Colorado’s board to discuss a strategy for addressing the backlog of pending Colorado renaming cases, and the Colorado board recently made its first name change recommendation. On September 16, 2021, the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board recommended changing the name of Squaw Mountain in Clear Creek County to Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain.

State Geographic Naming

Since the federal government does not have exclusive authority to name a geographic feature, states like Colorado can name (or rename) a mountain for state purposes. While there is no formal Colorado process for changing a name, there are historic examples where the General Assembly named a Colorado mountain peak, including some that occurred after the establishment of the modern BGN. The General Assembly adopted joint resolutions to name Mount Evans in 1895; rename Mount Wilson as Mount Franklin Roosevelt in 1937; and, in 1978, rename Lone Eagle Peak (named to honor Charles A. Lindbergh who had been known by the nickname “Lone Eagle”) as Lindbergh Peak. The 1978 Lindbergh Peak resolution directed that a copy of the resolution be sent to the BGN. In 1949, the General Assembly passed a bill to rename Veta Peak as Mount Mestas.

More recently, in 1995, the Colorado Senate approved a resolution supporting the efforts to name a mountain peak in honor of one of Colorado’s legendary early mountain climbers, Carl Albert Blaurock. Eight years later, on October 1, 2003, to honor Blaurock’s legacy of climbing, the BGN approved naming a 13,616-foot peak in Colorado’s Collegiate Peaks range as Mount Blaurock.

More recently, in 1995, the Colorado Senate approved a resolution supporting the efforts to name a mountain peak in honor of one of Colorado’s legendary early mountain climbers, Carl Albert Blaurock. Eight years later, on October 1, 2003, to honor Blaurock’s legacy of climbing, the BGN approved naming a 13,616-foot peak in Colorado’s Collegiate Peaks range as Mount Blaurock.Another wrinkle in a state-specific renaming is that some mountains are in similarly named federal lands. For example, Mount Evans sits in the federal Mount Evans National Wilderness Area. Even if Colorado changed the name of the mountain for state purposes, it could not change the name of the national wilderness area, which was designated by Congress.

Because it would not affect federal maps, signage, documents, or federally named lands, an exclusively state-based solution may not be the best approach for widespread acceptance of a new mountain name. Instead, working through the BGN’s process will get your (or your colleague’s) name on the map. While the federal renaming process can be lengthy, the first step is simple: head to the BGN’s website to review its policies and make a suggestion. If you’re a member of the General Assembly who would like to draft a resolution to change a mountain name at the state level, or suggest or support a federal change, please contact OLLS to put in your request.

Research from Nate Carr and Jacob Baus was used in this post.

-

The Mayflower Experiment

by Jery Payne

In August of 1620, a group of Puritans set sail from Southampton, England, on two ships named the Mayflower and the Speedwell. The destination was Virginia. The Speedwell, which had already seen leaks repaired several times, sprung a leak and took on water, so both ships went back to the closest port of Plymouth. Many of the Speedwell’s passengers squeezed themselves and their belongings into the Mayflower, and they set sail once again.

Because of the delay, the Mayflower crossed the Atlantic during storm season, which made the journey unpleasant. Many of the passengers were so seasick they could scarcely get up, and the waves were so rough that one person was swept overboard. After two months of misery, the Mayflower landed in Cape Cod, which wasn’t their destination. But they didn’t continue on to Virginia because, among other things, they were out of beer.

Then the colonists drafted and signed the Mayflower Compact. This compact promised to create a “civil Body Politick” governed by elected officials and “just and equal laws.” And they meant it.

The Puritans appear to have made what many modern Americans would consider a dystopian bargain. They gave up most freedom, individuality, and art for a society with low crime and low inequality. Our modern view of the Puritans is probably a little too influenced by the Salem witch trials and The Scarlet Letter. Although these portraits of the Puritans are not entirely wrong, they overlook a great deal. Put in context, a different picture is painted:

- The Puritans believed in public shaming. Along with the famous scarlet A for adultery, there was a B for blasphemy, a C for counterfeiting, a D for drunkenness, etc.

- They were strict. Wasting time was a criminal offense, and another law held, “If any man shall exceed the bounds of moderation, we shall punish him severely.” (The drafter must not have had a keen sense of irony.)

- The law required everyone to live in a family. If a Town official discovered a person living alone, the official would find a family and order the loner to join it.

- Teenage pregnancy rates were the lowest in the Western world and in some areas were zero.

- Murder rates were half of those in other American colonies.

- The Puritans valued education. Massachusetts was the first place to mandate universal public education. The law was nicknamed The Old Deluder Satan Act in honor of its preamble, which began “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the scriptures….” The Puritans founded Harvard and Yale. And the Massachusetts constitution guaranteed a public education to all citizens.

- There was remarkable wealth equality. The wealthiest 10 percent owned only 20 to 30 percent of the property, compared to about 75 percent today.

- The poor were treated with charity and respect. For example, a man’s heels were locked in the stocks for being uncharitable to a poor man.

- Women had more equality than in probably any other part of the world. Wife abuse was punished by a public whipping. A wife could divorce her husband for failing to meet his marital obligations, due to adultery, impotence, desertion, or other failures. For example, a husband was excommunicated in 1640 for having “denied conjugal fellowship unto his wife.” In another case, a woman admitted to committing adultery, but that was overlooked—belying the plot of The Scarlet Letter—because her husband admitted that he had “deserted her for several years.“

So although many of the Puritan’s attitudes and practices shock modern sensibilities, they were for their time remarkably egalitarian. Wealth distribution was actually more egalitarian than in modern America and almost every other civilization in history.

The settling of American’s 13 colonies is a social scientist’s dream come true. The lords and their servants settled Virginia and much of the coastal South, and the Puritans settled New England. The Puritans came to New England in large numbers because the English lords persecuted them. When Parliament went to war with King Charles I, the Puritans supported Parliament. And it was Puritan armies that by and large won the war, so the Puritans ended up ruling England for a time. When Parliament beheaded Charles I, many lords took the hint and came to Virginia. Although they both came from England, the two groups had very different cultures.

It’s not an accident that the descendants of the people who fought to reduce the king’s power over Parliament fought another civil war to end slavery. It’s not an accident that the descendants of the lords who fought for the rights of the king over Parliament fought against ending slavery. Although the first state legislature was established in Virginia, the American ideas about equality that inform the modern state legislature owe much to the Puritans.

Although Puritan rule ended up placing Oliver Cromwell on something that looked remarkably like a throne, the British civil war was a step toward parliamentary sovereignty. And this informed the attitudes of Americans.

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the oldest-written still-functioning constitution in the world. And it served as the model for the United States Constitution.

-

A Brief Evolution of Campaign Ads

by Robert Garcia

Soon we will begin to see a few campaign ads and posters, and soon after that they will be everywhere.

The modern campaign ad or poster is a slick thing, with Facebook- or Twitter-tested taglines or slogans and occasionally colorful trendsetting design. It’s nothing like its early forebears. As an element of political pop culture, the campaign poster has taken a long road to its present form.

In earlier times of campaign advertising the ads and posters were positive, informative, even charming.

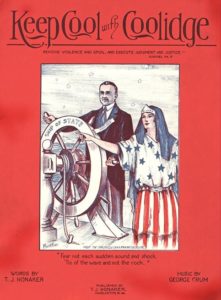

1924: Calvin Coolidge (Republican) v. John Davis (Democrat) v. Robert La Follette (Progressive)

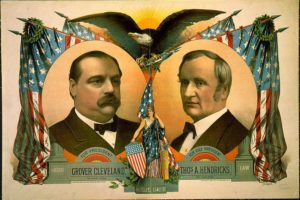

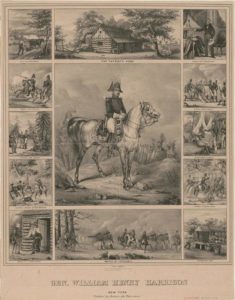

1924: Calvin Coolidge (Republican) v. John Davis (Democrat) v. Robert La Follette (Progressive)John Quincy Adams was the first presidential candidate to widely use posters in 1824, according to the Miller Center at the University of Virginia, but the oldest American campaign poster in the Library of Congress’s digital file was issued by presidential candidate William Henry Harrison in 1840.

William Henry Harrison in 1840.

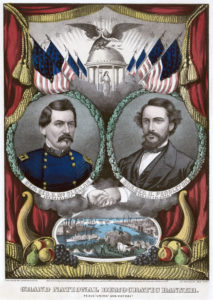

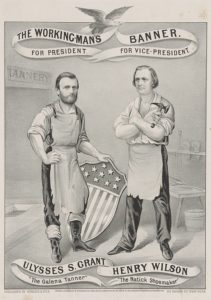

William Henry Harrison in 1840.In the 1800s, posters were far more detailed than they are today. Early campaign posters featured etched portraits of the candidates looking statesmanly, even regal, and were printed using the print technology of the day, sometimes inked in color. Extensive text was sometimes included with the portraits, and in some instances the text was the poster’s main feature.

1860: Abraham Lincoln (Republican) v. George B. McClellan (Democrat)

1860: Abraham Lincoln (Republican) v. George B. McClellan (Democrat) 1872: Ulysses S. Grant (Republican) v. Horace Greeley (Liberal Republican)

1872: Ulysses S. Grant (Republican) v. Horace Greeley (Liberal Republican)Steven Heller, a design expert and former New York Times art director, commented that it was harder to reproduce images than to reproduce text. They wanted to inform the public, and the public even then was fairly literate, so there was more of an emphasis on the written or printed word. Later into the 19th century as technology advanced, it became easier to reproduce things with wood or steel engravings. But by the end of the century, the camera had become more popular. Photos of candidates Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln routinely appeared on posters during their campaigns.

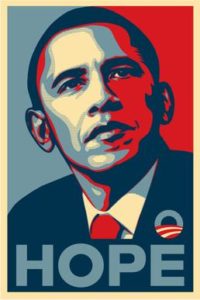

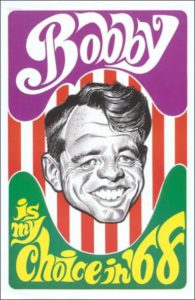

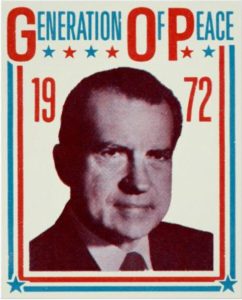

By the middle of the 20th century, a new design scheme became very popular—black-and-white photography with color backgrounds and large, easier to see and read text. Big, block-letter slogans and candidate names replaced the lengthy cursive script seen in the etched prints of the late 1800s, and bright primary colors replaced their dusty olives, sepias, and sun-yellows.

1968: Richard M. Nixon (Republican) v. Hubert Humphrey (Democrat) v. George Wallace (Independent)

1968: Richard M. Nixon (Republican) v. Hubert Humphrey (Democrat) v. George Wallace (Independent)Offset printing became popular for commercial printing in the 1950s, and color photographs, along with full color layouts, supplanted black-and-white by the time Richard Nixon ran for president in 1972.

1972: President Richard M. Nixon (Republican) v. Senator George McGovern (Democrat)

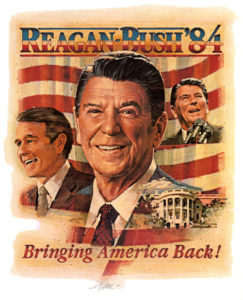

1972: President Richard M. Nixon (Republican) v. Senator George McGovern (Democrat)While candidates are now able to mass-produce color-photography posters in every election year, printing advancements haven’t necessarily made campaign posters more complex. The most widespread style, to this day, is the block-lettered rectangle using only the candidate’s last name and maybe a brief slogan or tagline. These signs hang on countless walls and populate countless front yards every couple of years.

This tells us printing capabilities don’t necessarily change the design imperative. Simplicity is what seems to be practiced most often.

Other technologies may have helped to popularize the simplistic design formula. With mass electronic media, candidates choose not to deliver platform information through posters, and the long scripts and etched portraits of the late 1800s would now look ridiculous. TV commercials and social media have taken over the function of higher-level messaging and image creation.

Today, the posters just remind us simply of what the candidates’ names are. Aesthetics and mnemonics are left mostly to computer generated art, font, and color scheme.

1984: Ronald Reagan (Republican) v. Walter Mondale (Democrat)

1984: Ronald Reagan (Republican) v. Walter Mondale (Democrat) -

Capitol Visitor Services: The Public Face for Legislative Council Staff

by Gwynne Middleton

While state capitol regulars may be most familiar with the nonpartisan Legislative Council Staff (LCS) for its hardworking crew who staff legislative committees, constituents are more likely to interact with LCS’s constituent services staff who assist legislators in responding to constituent questions, concerns, and requests for information, and their public relations team, Visitor Services.

Colorado State Capitol/Credit: Ashley Athey Housed on the ground floor of the capitol building, Visitor Services specializes in making the Colorado legislature approachable for the general public, welcoming visitors from as far away as Australia and as close as Cap Hill through their public tour programming. With approximately 70,000 people taking official tours each year, Visitor Services’ docents offer an insider’s look at the architecture and history of one of the most memorable public buildings in the state.

Recently I had the opportunity to connect with the Visitor Services’ Assistant Manager, Erika Osterberg, and pick her brain about the many ways the capitol tour serves as a bridge between the legislature and the public they are committed to serving. Below you’ll find our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

How does the capitol tour help LCS fulfill its mission?

Our mission is to inspire and educate the public about our historic statehouse and the work of our General Assembly. While our work is a bit different than that of our colleagues in LCS, we share a deep pride and commitment to service as ambassadors to the capitol and the state of Colorado. Providing accurate, nonpartisan, and unbiased information in a professional manner is a responsibility we take very seriously and something we require each guide to honor.What does a typical tour look like, and what elements of the tour are unique to Colorado?

Our public tours last about one hour and include a brief historical overview of our state; information about the architecture, construction, and materials that make up the capitol; capitol artwork; and the legislative process. All public tours also offer an opportunity for visitors to make a trip up to the dome observation area to enjoy our incredible 360-degree view of the Front Range, downtown Denver, and the plains to the east.For groups with reservations, we offer this tour by default but can also build into their schedule a docent-led tour of Mr. Brown’s Attic Museum. Additionally, during the legislative session, we help coordinate a “legislative tour,” where groups can spend time observing work on the floor and learn in greater detail about the work of the General Assembly. These tours are primarily designed for student groups, and Visitor Services leads these tours alongside staff from House and Senate Services.

We have a very gifted team of guides comprised of volunteers and part-time work-study students from the University of Colorado at Denver and Metropolitan State University of Denver, as well as five full-time temporary college student “summer guides” who work from May-August and whose enthusiasm and love for this building is extraordinary.

We see and hear many wonderful compliments about our knowledgeable and friendly staff who bring this building to life for so many visitors. While in many ways the beauty of this building speaks for itself, touring with a guide gives one a deeper appreciation of the history and impact of the capitol and the work that happens here.

Why do you think offering this tour to the public matters?

In addition to educating the public about the rich history and heritage of Colorado, we recognize our unique opportunity in helping them better understand the legislative process and the importance of public participation in state government.Many visitors—both local and international— are surprised to learn that the public is welcome to observe work on the floor or that they may testify in committee, for example. We see it as an important responsibility to demystify work that some people find intimidating in its complexity.

Ms. Osterberg’s insights into Visitor Services’ tour programming highlight the long-term value of welcoming people from all walks of life to the capitol. Opportunities to witness the House of Representatives or Senate in action from the galleries of their respective chambers and to stroll through the hallowed halls of this historic building may make visitors feel more invested in following the state legislative process because of their newly informed connection to this physical landmark that represents Colorado and its citizens.

Free public tours start on the first floor of the capitol and occur Monday through Friday, on the hour every hour between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. Groups with fewer than 10 members may join these tours and should arrive at least 20 minutes early because the tours are popular and often reach the 30-person limit before the tour begins. If visiting with more than 10 people, be sure to make a reservation via Visitor Services’ online booking form. These reservations can be made up to one calendar year in advance.

For those who are unable to participate in an official tour of the building, the Capitol Building Advisory Committee, in conjunction with LCS’s Visitor Services, is currently working through a proposal to develop an audio tour that visitors can complete at their own pace. For more information about this proposed audio tour option, contact Visitor Services.

-

Does My Bill Really Enact a Compact?

By Thomas Morris

Drafters are often given a draft bill that purports to be a compact — sometimes called an interstate compact. However, in at least some instances, it is not a compact — it is a model law that the proponents wish to invest with the gravitas of a compact. They are very different things that need to be treated very differently.

Compacts

The states’ ability to bind themselves to a compact is governed by Article I, Section 10 of the United States Constitution:

No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay. (emphasis added)

A good example of a compact is the Colorado River Compact, which is codified in article 61 of title 37, C.R.S. This compact was entered into by the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming and was approved by Congress. It apportions the water of the Colorado River among the seven states. The statute codifying the compact quotes the compact in its entirety, including the provision indicating that it becomes effective only after at least six of the compacting states’ legislatures approve it and the listing of the signatures of the compacting states’ authorized representatives.

A fully executed compact is, simultaneously, three things (usually):

- A contract between at least two states, typically negotiated by designees of the governors or other official representatives of the compacting states (not a private organization). If a compact is violated, the compacting states’ exclusive litigation remedy is to sue each other directly in the United States Supreme Court. Individuals have no standing to enforce a compact unless the compact explicitly or impliedly provides a private right of action.

- A state law enacted by the contracting states’ legislatures. Because a compact is a contract, and a contract cannot be unilaterally modified by any of the contracting parties, if the bill is actually a compact, it needs to be enacted without any unauthorized changes. Look at, e.g., most of the parts in article 60 of title 24, C.R.S., where most compacts (other than with regard to water) are codified. Typically there is a C.R.S. section that states a short title (“‘This part 16 is known as the Interstate Corrections Compact’”) and another C.R.S. section that reproduces the compact as is—warts and all. There should be either a direction to the governor or a designee to enter into the compact or a portion of the compact that includes the signatures of, or other acknowledgement of execution by, the compacting states. However, sometimes a compact will specify that it becomes effective if it is enacted in “substantially” identical form by the compacting states’ legislatures. This allows the General Assembly to amend the compact, but it is unclear when the “substantially identical” standard would be violated.

- A federal law. A compact that increases the power of states at the expense of the federal government cannot take effect under the federal constitution unless Congress approves it. This element is not required if the compact does not increase the states’ power by encroaching on federal authority, as determined by the United States Supreme Court in the case of Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U.S. 503.

A prominent example of a compact between states that Congress did not approve is the 1861 Constitution of the Confederate States of America. With this example, one can see why the Founders were concerned about the states entering into at least some types of agreements among themselves.

Model Laws and Uniform Laws

In contrast, at least some of the documents given to drafters that purport to be compacts are really just model laws. There has been no contract between the states nor any plan to enter into one. The proponents are organizations or individuals that would benefit from having similar laws in various states, not the states themselves. The laws are enforceable by parties other than the enacting states. The laws are enacted only in more or less similar form. And there has been no approval by Congress nor any plan to get it.

Compacts are distinct from both uniform acts, which have been proposed by the Uniform Law Commission and approved by the American Bar Association, and model laws, which are produced by non-governmental bodies of legal experts. While some of the legal results are the same – state law is identical or virtually so in more than one state – the subject matter of the two types of laws (model and uniform laws versus compacts) fundamentally differs and the process of formulating and enacting the two types of laws is usually also quite distinct.

So it is incumbent on the drafter to figure out, precisely, what he or she has been given before the bill can be finalized. If it’s truly intended to be a compact, even if the other two elements – contract and congressional approval – are not yet in place, it should generally be codified as a new part in article 60 of title 24. And unless it specifies that it can be amended, so long as it is enacted in substantially the same form by all the compacting states, the document should not be altered in any way, including by amendment. If this is the case, the drafter and contact people should make that very clear to the bill sponsor and any other legislator who may try to amend it.

If the document is really just a model law, it should not be codified as a part in article 60 of title 24, and the bill sponsor or any other legislator may make any changes they choose. But please don’t call it a compact!

-

Tips for an Effective Legislator

by Gwynne Middleton

By the time legislators reach the hallowed halls of the State Capitol, they have mastered many important leadership skills that will serve them well in working with constituents, staff, and other elected officials to improve the lives of Coloradans through their policy decisions. Still, in the midst of a fast-paced legislative session, it’s easier than you’d think for what seems like a minor misstep to undermine a legislator’s ability to achieve his or her legislative goals. Below are 15 important tips shared from the National Conference of State Legislatures to help our senators and representatives legislate like champs.

1. Honor the Institution

To succeed in its goal to serve its citizens, government requires trust between citizens and their representatives. Appeal to the best interests of the electorate, represent your constituents’ needs, focus on your values and what you want to do while in office, and direct your energy toward fulfilling those promises. You ran for office to make a positive difference in Colorado. Don’t lose sight of the vision you have for making that difference.

2. Take the High Road

In matters of public trust, appearances matter. Government thrives on ethical transparency. Perfectly legal actions can still look fishy to the public. Since public officials are held to higher standards than average citizens, avoiding situations that carry the appearance of impropriety will encourage public confidence in your legislative work. For the sake of the General Assembly and your career in public service, understand Colorado’s ethics codes and adhere to them.

3. Master the Rules

It’s no easy feat to become an expert on intricate legislative process rules, but the more adept you are at knowing the rules, the better you’ll be able to participate in the process, helping yourself and your constituents be heard. The most effective way to learn your legislative chamber’s rules is through application. Don’t be afraid to keep your rules book nearby so that you can call upon them when you’re unclear about a particular legislative process.

4. Know Where to Find Help

From fellow legislators and legislative staff to the folks in the governor’s office and the executive branch agencies, your political community is your best resource for gathering nuanced information about an issue. Setting aside just 20 to 30 minutes before a committee meeting to review bills on the agenda with legislative staff will help you bring your A-game to committee discussions.

5. Manage Your Time

Stay organized, prioritize what’s most important to accomplish, meet deadlines, and only commit to what you consider important. It’s easy to overcommit in an environment where numerous stakeholders are jockeying for your attention. If you tend to be a “yes” person, be careful and protective of your time. It’s limited, and if you’re overcommitted, you won’t be able to do your best work as you juggle the overwhelming schedule. Instead of giving attention to that which you care most deeply about, you’ll spread yourself thin and wind up disappointed.

Managing your time is also about punctuality. If you’re flying by the seat of your pants because of multiple commitments, your punctuality may suffer, creating an unprofessional appearance. People won’t take you seriously if they feel that you aren’t on top of your game, and in some cases, being late to meetings will cause your colleagues and constituents to believe you don’t respect their time.

6. Develop a Specialty

Your time as a legislator is limited. Develop a legislative agenda that’s not only rooted in your personal background, previous experiences, and policy expertise but tightly focused on your district’s needs. By cultivating a policy focus during your tenure, you can become the member others seek out for expertise. The kicker? You’ll practice valuable negotiation skills and gain the reputation of being a serious, committed lawmaker whom people will clamor to support.

7. Vote your Conscience

It’s not always an easy choice to vote your conscience, especially on controversial issues when your belief conflicts with constituents who voted for you to represent them or if a campaign contributor tries to sway your vote. After gathering information from all sides, vote as you see fit, but be prepared to explain your votes to constituents. By communicating with your constituents about the reason behind your position, you create an environment of transparency, and transparency has been proven to increase trust. Even if they don’t agree with your decision, they’ll be in a better position to respect you for the decision you made.

8. Don’t Burn Bridges

Be open to compromise, even with those who may not be natural allies. Create a broad set of associates, even beyond your chamber. Maintain a professional demeanor and keep emotions in check. Even if a colleague doesn’t like you, you’ll earn respect for being level-headed.

9. Keep Your Word

You’re only as effective as your reputation. Your colleagues rely on your credibility. Make only promises you can keep. While the best way to keep your word is to not commit until you have all the facts, if you learn information that would change your vote, be transparent about why you need to change your vote to prevent hard feelings.

10. Be Careful What You Agree to

To keep your word, it’s important to avoid casually agreeing to cosponsor bills that you aren’t invested in. Sometimes you may have to vote against a bill that you’ve agreed to sign on to sponsor. Before agreeing to be sponsor, give yourself 24 hours to make sure you understand the bill. Just because you like a person and usually trust that person’s views doesn’t mean you’ll always agree. If the sponsor of the bill cares deeply about your support of their bill, they will wait a day for your decision.

11. Don’t Hog the Mike

Even if you’re an expert on every bill that’s up for debate, be selective about which bills you discuss before the chamber. If you’re always in the well speaking on every bill, you risk diminishing your power as a speaker. Quality should always win out over quantity in public speaking. By being judicious about your mic time, when you do speak, your colleagues will be more likely to listen when you step into the limelight.

12. Stay in Touch with Your Constituents

Always remember the people who elected you. Hire the aides who are best able to help you maintain strong contact with your constituents.

13. Be a Problem Solver

Rather than getting caught up in the drama that often accompanies controversial issues, use your skills and your office to help your community focus on solutions. Work with state agencies and local governments to find a solution that will benefit the most people in your community.

14. Work with the Media

Reporters care deeply about their responsibility to keep their viewers informed with factually accurate news. Reach out regularly to reporters to share your position on issues, but be sure to focus on the policy process and the issues rather than only on partisan differences and conflict. Make your information easy to understand and use, and, when the media does a good job of reporting fairly, remember to acknowledge that good work.

15. Self-care and Presence

The weighty responsibilities and accolades that accompany holding public office can be unhealthy substitutes for intimacy, fellowship, and taking care of yourself and the people you care about. The attention of others is no substitute for an interior life. Maintaining an interior life will help you feel more at ease during the times in life when professional commitments can pull you in many directions.