Year: 2022

-

Bill Sponsor Basics – an Overview

by Jennifer Gilroy, Michael Dohr, and Jessica Chapman

Editor’s note: This article was originally written by Patti Dahlberg and Jennifer Gilroy and published on December 22, 2016. The article has been edited and updated.

Bill requests are coming in hot here at the OLLS and drafting season is well underway. That means now is probably a good time to review some of the basics of bill sponsorship.

Bill Sponsor Basics

Prime Sponsorship – First House. The legislator who introduces and carries a bill is called the prime sponsor of the bill. Bills cannot be introduced without a prime sponsor. Every bill must have at least one prime sponsor in each chamber (or house) before it can be heard in both chambers. In both the House and the Senate, the prime sponsor (and joint prime sponsor if there is one) is responsible for explaining the bill in committee and in debate on the House or Senate floor. A prime sponsor also typically arranges for witnesses to testify in favor of the bill in committee.

A legislator can be the first house prime or joint prime sponsor for only five bills, unless the legislator has special permission from the committee on delayed bills (leadership) to carry more. But a legislator can agree to be the prime or joint prime sponsor of a bill in the second house on as many bills as the legislator wants.

Prime Sponsorship – Second House. The prime sponsor in the first house (also known as the house of introduction) is responsible for asking a legislator in the second (or opposite) house to carry the bill in that house. The prime sponsor in the first house does not have to identify a second house prime sponsor before the bill is introduced in the first house, but the bill must have a second house prime sponsor before the bill can be heard on third reading in the first house.

Before a bill can move to the second house, the second house prime sponsor must inform the House Chief Clerk or the Secretary of the Senate of that legislator’s intent to serve as the second house prime sponsor. Prime sponsors’ names in both houses are listed on the bill in bold text.

Sponsorship and Co-sponsorship. When legislators want to show support for a bill, but not take on the responsibility of actually carrying the bill, they may sign on as sponsors or co-sponsors of the bill. If a legislator adds the legislator’s name to a bill before it is introduced, the legislator is a sponsor of the bill. If a legislator adds the legislator’s name to a bill after it is introduced, the legislator is referred to as a co-sponsor. Co-sponsors are added immediately following adoption of a bill on third reading.

Joint Prime Sponsorship

Joint Prime Sponsorship. When two legislators in one house want to carry a bill together, we refer to them as joint prime sponsors. A bill that has joint prime sponsors in one house may or may not have joint prime sponsors in the other house. The rules for joint prime sponsorship are similar for the House (House Rule 27A(b)) and the Senate (Senate Rule 24A(b)).

Joint prime sponsorship counts against both legislators’ five-bill limit in the first house. Both joint prime sponsors must verify their desire to be joint prime sponsors. A legislator cannot be added as a joint prime sponsor in the first house if that legislator has already submitted five bill requests, unless that legislator has received permission from leadership. The prime sponsor in the first house must notify the House Chief

Clerk or the Secretary of the Senate, as appropriate, of any changes in bill sponsorship so that the changes are reflected in subsequent versions of the bill.

Clerk or the Secretary of the Senate, as appropriate, of any changes in bill sponsorship so that the changes are reflected in subsequent versions of the bill.Joint prime sponsorship does not count against the five-bill limit for either legislator in the second house. Again, both joint prime sponsors must verify their desire to be joint prime sponsors.

Joint prime sponsors are typically determined prior to the bill’s introduction. However, in limited circumstances, joint prime sponsors may be added or changed after introduction immediately after second reading but prior to adoption of the bill on third reading. The House and Senate front desk staff can help with this process.

Bill Sponsor FAQs:

How do I add sponsors to my bill before it is introduced?

Before your bill is introduced you can invite other legislators to be sponsors on your bill via the Electronic Sponsorship feature in iLegislate. Electronic Sponsorship operates similarly to an Evite: You may invite legislators to sponsor your bills and you may share draft files with them. Those legislators may choose whether they want to be a sponsor on your bill. If a legislator wants to be a sponsor on your bill but is not able to indicate that through iLegislate and the bill is still in the Office of Legislative Legal Services’ (OLLS) possession, the legislator may simply notify the OLLS in person, by phone, or by email that the legislator would like to be a sponsor on another legislator’s bill. A legislator may not be added to one of your bills as a sponsor without that legislator’s permission and a legislator will not be added to your bill without your permission. Once your bill is delivered by the OLLS to your chamber’s front desk, the OLLS cannot add any more sponsors. (In special circumstances, the House or Senate front desk staff may be able to add sponsors before a bill is printed, but you must contact your chamber’s front desk staff to see if this special circumstance exists.)

The OLLS will deliver your prefile bill (your first bill to be introduced) directly to the House or Senate front desk because that bill must be introduced on the first day of session. The OLLS will deliver your other bills to the front desk or to you, as you direct. Do not contact the OLLS to add sponsors after your bill has been delivered to the front desk or to you. Once a bill is delivered, all sponsor additions or changes must go through House or Senate staff.

How do I add sponsors to my bill after it is delivered for introduction?

If you direct the OLLS drafter to deliver your bill (other than your prefile bill) to you personally and not your chamber’s front desk, the OLLS staff will give the bill to the sergeants who will then deliver it to you. If the bill is delivered to you prior to its introduction deadline you can show it to other legislators and have them sign the sponsor form attached to the bill or go through iLegislate. The bill delivered to you will include a sponsor form stapled to a heavier sheet of green paper (if you’re a Representative) or cream-colored paper (if you’re a Senator). This is called a bill back. Please do not separate the bill from the bill back and sponsor form.

After you give the bill back (and attachments) to the front desk, the front desk staff will review the sponsor form and add the names of those legislators who have signed the form indicating their desire to be sponsors of your bill. These sponsor names will appear on the introduced version of the bill. Sponsors cannot be added to your bill after the front desk has sent it out for printing. After your bill has been introduced, however, other legislators may add their names as co-sponsors following passage of your bill on third reading.

Feel free to contact the OLLS front office, your drafters, or the House and Senate front desks with any questions regarding bill sponsorship. You may contact the OLLS staff to inquire about sponsorship prior to your bill being delivered to the House or Senate for introduction, at (303) 866-2045 or olls.ga@coleg.gov. Once your bill has been delivered for introduction, you may contact the House or Senate front desk staff with your sponsorship questions.

-

Different Roles Under One Dome: An Analysis of Partisan and Nonpartisan Legislative Staff

by Alana Rosen

As we quickly approach the New Year and the 2023 legislative session, the Colorado Capitol will soon be filled with legislators, partisan legislative staff, nonpartisan legislative staff, executive agency officials, lobbyists, and the public. With so many individuals in the building, you may be asking yourself, “What is the difference between partisan and nonpartisan legislative staff if they all serve the Colorado General Assembly?”

Partisan legislative staff work for or strongly support one side, party, or legislator. In Colorado, the House of Representatives and the Senate each have a Democratic and Republican caucus staff made up of partisan legislative aides, interns, and staff. Partisan staff work to advance

the policy agenda of a legislator or that person’s caucus, as well as assist with requests from constituents. Partisan staff are more likely to discuss political and personal beliefs in the workplace.

the policy agenda of a legislator or that person’s caucus, as well as assist with requests from constituents. Partisan staff are more likely to discuss political and personal beliefs in the workplace.Nonpartisan legislative staff, on the other hand, aim to serve all legislators impartially— regardless of party—ensuring their work is objective, balanced, and accessible. To fulfill this function properly, nonpartisan staff must provide the highest level of service to all members, under all circumstances, so the General Assembly feels confident in their impartiality. When nonpartisan staff participate in partisan political activities, public confidence in the legislative process can be undermined by creating a perception that nonpartisan staff may not provide the unbiased support necessary to enable the General Assembly to make informed decisions that best serve the public interest.

Nonpartisan legislative staff have a compelling interest to protect both the actual and perceived integrity of the legislative process by placing narrowly tailored restrictions on employees’ political activities. For this reason, nonpartisan staff are prohibited from fundraising for a partisan candidate, making political contributions, actively participating in the campaign of a partisan candidate, actively participating in a political party or organization, or running for political office. Additionally, nonpartisan staff do not discuss politics or personal beliefs with legislators, partisan legislative staff, executive agency officials, lobbyists, or the public.

During the interview process, prospective staff are often asked extensive questions regarding their ability to be nonpartisan and whether they have any reservations about being nonpartisan. It is a code of conduct that nonpartisan staff adopt in order to serve the legislature fairly and impartially.

You may now be wondering, “Who are the nonpartisan staff so I can avoid engaging them in political discussions?” In addition to your nonpartisan Senate Services staff and staff of the House of Representative, there are four nonpartisan legislative agencies created in state law that serve the Colorado General Assembly with oversight from a legislative committee : the Office of Legislative Legal Services (OLLS), Legislative Council Staff (LCS), Joint Budget Committee Staff (JBC), and the Office of the State Auditor (OSA).[1]

The OLLS is the nonpartisan in-house counsel for the General Assembly. Among its many tasks, the OLLS writes laws, produces statutes, reviews administrative rules, comments on initiated measures, and serves as a resource of legislative information for the public.

The LCS is the permanent research staff of the General Assembly, providing public policy research at the request of the members. The LCS provides support to legislative committees, responds to requests for research and constituent services, prepares fiscal notes, provides economic and revenue forecasts, and performs other centralized legislative support services.

The JBC is the General Assembly’s permanent fiscal and budget review agency. The JBC writes the annual appropriations bill, also known as the Long Bill, for the operations of state government. The JBC is charged with analyzing the management, operations, programs, and fiscal needs of the departments of state government and makes recommendations to the members of the General Assembly as they build the state’s budget.

The OSA seeks to hold state government agencies accountable through performance, financial, and information technology audits of all state departments, colleges, and universities. Audits provide solution-based recommendations that focus on reducing costs, increasing efficiency, promoting the achievement of legislative intent, improving effectiveness of programs and the quality of services, ensuring transparency in government, and ensuring the accuracy and integrity of financial information to hold government agencies accountable for the use of public resources.

With so many new members in the General Assembly this year, a clearer understanding of the differences between the roles of partisan and nonpartisan legislative staff is helpful as we enter the 2023 legislative session. If you’re a new legislator and have questions, please feel free to contact the OLLS at 303-866-2045 or olls.ga@coleg.gov.

[1] See article 3 of title 2, Colorado Revised Statutes.

-

High School Football Prayer Gets the Ultimate Replay Review

By Alana Rosen

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 597 U.S. ___ (2022).

In many states, high school football is seen almost as an unofficial religion. On June 27, 2022, the United States Supreme Court brought high school football and religion even closer by announcing its decision in favor of Mr. Joseph Kennedy in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District.

Mr. Kennedy worked as a football coach for Bremerton High School in Washington State from 2008 to 2015. Since his hiring in 2008, Mr. Kennedy engaged in a practice of “taking a knee at the fifty-yard line to say a quiet prayer at the end of football games for about 30-seconds.” Initially, Mr. Kennedy prayed on his own but, over time, some players asked whether they could pray alongside him. Some players invited opposing players to join too. Mr. Kennedy began giving motivational speeches, with a helmet held aloft, and would deliver speeches with “overtly religious references,” which Mr. Kennedy described as prayers, while players kneeled around him. On September 17, 2015, after learning of the post-game prayers, the Bremerton School District (District) asked Mr. Kennedy to stop the practice of incorporating religious references or prayer in his post-game motivational talks on the field because the District did not want to violate the Establishment Clause. [1]

On October 14, 2015, Mr. Kennedy sent a letter to school officials through his attorney, stating that he would resume his practice of praying at the 50-yard line because he felt “compelled” by his “sincerely-held religious beliefs” to offer a “post-game personal prayer.” He asked the District to allow him to continue the “private religious expression” alone and stated that he would wait until the game was over and the players had left the field.

Thereafter, Mr. Kennedy and his attorney had a back-and-forth with the school district. Mr. Kennedy wanted to exercise his sincerely-held religious beliefs to offer a post-game prayer and the school expressed concern that such a prayer would lead a reasonable observer to think that he was endorsing prayer while on duty as a District employee. The District also offered accommodations for religious exercise that would not be perceived as endorsing religion or interfere with his job performance.

Undeterred, Mr. Kennedy continued to pray at the 50-yard line while post-game activities were still ongoing, and as a result, the District placed him on paid administrative leave for violating its directives by thrice kneeling on the field and praying immediately following games before rejoining the players for post-game talks. On August 9, 2016, Mr. Kennedy filed suit in the Western District of Washington contending that the District violated his rights under the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment.

In this case, the United States Supreme Court considered whether a public school employee who says a brief, quiet prayer while at school and visible to students is engaged in government speech, which is not protected by the First Amendment. And whether, assuming that such religious expression is private and protected by the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses, the Establishment Clause compels public schools to prohibit religious expression.

In this case, the United States Supreme Court considered whether a public school employee who says a brief, quiet prayer while at school and visible to students is engaged in government speech, which is not protected by the First Amendment. And whether, assuming that such religious expression is private and protected by the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses, the Establishment Clause compels public schools to prohibit religious expression.Since the founding of this country, the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment—the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause—have been understood to jointly demand government neutrality towards religion. The Free Exercise Clause recognizes the right to believe and practice a faith, or not. The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from making any law “respecting an establishment of religion.” The Free Speech Clause protects religious speech.

A plaintiff bears a certain burden to demonstrate an infringement of rights under the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses. In this case, the Court held that Mr. Kennedy discharged his burdens under the Free Exercise Clause and the Free Speech Clause, which were “sincerely motivated religious exercises.”

To determine whether the government violated the Free Exercise Clause, the Court considered whether a government policy is neutral and generally applicable. Justice Gorsuch, writing for the six-member majority, stated that a government policy will not qualify as neutral if it is specifically directed at a religious practice. Additionally, a government policy will fail the general applicability requirement if the policy prohibits religious conduct while permitting secular conduct that undermines the government’s asserted interests in a similar way or if it provides a mechanism for individualized exemptions.

Here, the Court determined that the District’s challenged policies were neither neutral nor generally applicable. The Court held that the District’s policy was not neutral towards religious conduct. The Court further held that the District’s challenged policy failed the general applicability test because the District had advised against renewing Mr. Kennedy’s contract because he “failed to supervise student-athletes after the game.” The Court noted that any sort of post-game supervision requirement must be applied evenly across the board, and while other coaching staff briefly visited with friends or took personal calls, Mr. Kennedy chose to briefly pray at the 50-yard line.

The Court then analyzed whether the District violated Mr. Kennedy’s freedom of speech. The Court held that Mr. Kennedy offered his prayers in his capacity as a private citizen, which did not amount to government speech because the prayers were not ordinarily within the scope of Mr. Kennedy’s duties as a coach. To come to this conclusion, the Court applied the “Pickering – Garcetti” two-step test.[2] The first step of the test is to determine whether a public employee is speaking as a the public employee doing official duties or whether the public employee is speaking as a citizen addressing a matter of public concern. The second step of the test is that the government may seek to prove that its interests as an employer outweigh an employee’s private speech as a matter of public concern.

In applying the “Pickering-Garcetti” test, the Court first determined Mr. Kennedy was speaking as a private citizen as “Mr. Kennedy’s prayers did not ‘owe [their] existence’ to Mr. Kennedy’s responsibilities as a public employee.” The Court stated that the timing and circumstances of Mr. Kennedy’s prayers confirm this point because the prayer was conducted during the post-game period. Justice Gorsuch stated that “[t]eachers and coaches served as vital role models, but [the District’s] argument commits the error of positing an excessively broad job description by treating everything teachers and coaches say in the workplace as government speech subject to government control.” In the dissent, however, Justice Sotomayor argued that Mr. Kennedy was on the job as a school official on government property when he incorporated a public, demonstrative prayer into government-sponsored school related events as a regularly scheduled feature to those events.

The District argued that it was essential to suspend Mr. Kennedy to avoid violations of the Establishment Clause and relied on the Lemon test—a three-step test established in Lemon v. Kurtzmann—and its progeny to determine Establishment Clause violations. [3] Justice Gorsuch, however, said that the Court had abandoned Lemon and the related endorsement test. The Court argued that these tests invited chaos and led to differing results in materially identifiable cases. Instead, in place of Lemon, the Court instructed that the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by “reference to historical practices and understandings.” Justice Sotomayor questioned the Court’s new “history and tradition” test because the Court did not provide guidance on how to apply the test, potentially causing confusion to school administrators, faculty, and staff trying to implement it.

What does Kennedy mean for Colorado?

Right now, it is unclear how Kennedy will affect Colorado and education law. While teachers or school personnel could bring forth similar arguments for their religious conduct, courts will ultimately have to determine what the “history and tradition” test is in order to answer whether religious conduct violates the Establishment Clause. Because the Court did not provide guidance on how to apply the “history and tradition” test, it will be up to the lower courts to decide.

[1] The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from making any law “respecting an establishment of religion” and it bars the government from taking sides in religious disputes or favoring or disfavoring anyone based on religion or belief (or lack thereof).

[2] Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006) (holding the First Amendment does not prohibit managerial discipline of public employees for making statements pursuant to employees’ official duties); Pickering v. Bd. of Ed. of Township High Sch. Dist. 205 Will Cty., 391 U.S. 563 (1968) (holding a teacher’s right to speak on issues of public importance may not furnish the basis for his dismissal from public employment).

[3] Lemon v. Kurtzman, 401 U.S. 602 (1971) (establishing a three-part test to determine First Amendment Establishment Clause violations).

-

Remarks on the “Unremarkable” Carson v. Makin

by Jacob Baus

“Unremarkable”

Is this a judgmental slight from Downton Abbey’s Mr. Carson, or a harsh but fair critique from TV personality Carson Kressley? Neither! This is how U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts described the holding in a recent case, Carson v. Makin.

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states, in part, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; . . .”, and these clauses are commonly referred to as the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause. Carson is the latest case concerning the provision of public money to a religious-affiliated school and how states have attempted to navigate the issue with respect to these clauses.

Maine is a sparsely populated state, and many of its school districts do not operate a secondary school. Consequently, Maine created a tuition assistance program for families whose resident school district does not provide a secondary school education. An eligible family chooses a school, and the resident school district sends tuition assistance payments to the school, if the school is eligible.

To be eligible, a school must satisfy certain education-related requirements, may be public or private, and must be nonreligious. Maine excluded religious schools from the program based on a position that the provision of public money to religious schools violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Eligible families sued Maine’s Commissioner of Education, arguing the program’s nonreligious requirement violated the Free Exercise, Establishment, and Equal Protection Clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

Applying principles from the related Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer and Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue cases, the Court arrived at a similar conclusion in Carson; that is, excluding religious schools from program eligibility because of their religious character violates the Free Exercise Clause. This reliance on consistent and recent precedent may explain why Chief Justice Roberts found the conclusion in this case to be unremarkable. Nevertheless, the Court addressed a few significant considerations and arguments in reaching its conclusion.

First, the Court noted that the flow of public funds to a religious institution through the independent choice of a benefit recipient does not offend the Establishment Clause. Consequently, excluding religious schools from program eligibility promotes stricter separation between church and state than the Establishment Clause requires. And, the Court continued, a state’s interest in separating church and state further than the Establishment Clause requires is not sufficiently compelling in this case to justify a Free Exercise Clause violation to deny a public benefit because of religious character.

First, the Court noted that the flow of public funds to a religious institution through the independent choice of a benefit recipient does not offend the Establishment Clause. Consequently, excluding religious schools from program eligibility promotes stricter separation between church and state than the Establishment Clause requires. And, the Court continued, a state’s interest in separating church and state further than the Establishment Clause requires is not sufficiently compelling in this case to justify a Free Exercise Clause violation to deny a public benefit because of religious character.Second, Maine argued that the benefit at issue was providing the “rough equivalent of a public school education” and therefore must be secular. The Court rejected this argument, citing numerous facts about the program undermining this assertion. The Court ultimately concluded that the only real manner in which an eligible private school is the “equivalent” of a public school under the program is that it must be secular, thereby supporting the Court’s position that the program excludes based upon religious character.

Third, Maine argued that the nonreligious requirement was not religious character-based, but rather religious use-based. Maine argued that because religion permeates everything a religious school does, the nonreligious requirement was effectively use-based and therefore permissible. Maine argued this distinction because the Court has previously held that a state’s religious use-based exclusion was constitutionally permissible.[1] The Court rejected this argument, concluding that a prohibition on character-based discrimination is not grounds for engaging in use-based discrimination.

What does Carson mean for Colorado?

Nothing in the Carson decision requires Colorado to provide public money to support private schools. The Carson decision reaffirms an important point of clarity from the Espinoza decision:

[A] State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.

It is not novel to state that the General Assembly must be cautious if a public program or benefit appears to categorically exclude a religious school or institution. It appears from Carson, Espinoza, and Trinity, that the Court is likely inclined to find that religious exclusions are character-based, and therefore in violation of the Free Exercise Clause, even if a state has a no-aid provision similar to article IX, section 7 of the Colorado Constitution.

Although it is always difficult to predict what happens next, the Court will likely have future opportunities to examine whether there is a meaningful constitutional distinction between exclusions that are character-based versus use-based in nature and how states should consider issues that fall in an often-found tension between the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses.

[1] Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712 (2004) (A publicly funded Washington scholarship excluded the use of the scholarship for a degree in theology. The United States Supreme Court concluded the exclusion was not unconstitutional.)

-

2022 Interim Committee Recap – Part 2

Yesterday, we brought you Part 1 of the 2022 Interim Committees Recap series. Today in Part 2, we’re covering the remainder of interim committees and their recommended legislation, which were considered for introduction at the Friday, October 14, Legislative Council meeting. Click here to listen to the meeting.

Yesterday, we brought you Part 1 of the 2022 Interim Committees Recap series. Today in Part 2, we’re covering the remainder of interim committees and their recommended legislation, which were considered for introduction at the Friday, October 14, Legislative Council meeting. Click here to listen to the meeting.Transportation Legislation Review Committee

The Transportation Legislation Review Committee met twice. At the August 9 meeting and the September 10 meetings, the committee heard presentations:

- From public highway authorities;

- From the Colorado Department of Transportation;

- About climate reduction goals and reducing vehicle miles traveled;

- From the Colorado Motor Carriers Association;

- About driver education requirements;

- From the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition

- About fleet license plates;

- From the Regional Transportation District ;

- From Bicycle Colorado and Denver Streets Partnership;

- From Toyota;

- From the Division of Motor Vehicles;

- About transportation and Senate Bill 22-180;

- From the Front Range Passenger Rail District;

- From Colorado Association of Transit Agencies; and

- About local transportation and Senate Bill 22-180.

The committee also drafted and considered ten bills, but ultimately voted to advance the following bills:

- Bill A – Registration of fleet vehicles that are part of rental vehicle fleets. The bill allows the operator of a rental vehicle fleet (fleet operator), if authorized by the Department of Revenue, to transfer license plates from one fleet vehicle to another when the fleet operator transfers or assigns the owner’s title or interest in the fleet vehicle from which the number plates are being transferred.

In addition, subject to current statutory requirements relating to the use of approved third-party providers, the department, to the extent feasible, is required to allow an owner of a rental vehicle fleet that is authorized to transfer license plates to maintain its own inventory of new number plates and to use a third-party provider to handle all or any portion of both its vehicle registration, lien, and titling needs and its number plate inventory ordering, management, and distribution needs.

- Bill B – A requirement that motor vehicle drivers move over or slow down to mitigate the risk their vehicles present to stationary vehicles on the road. The bill requires a person to move over, if possible, or slow down to a safe speed when a vehicle is on the side of the road displaying flashing hazard lights or warning lights. The current law that imposes the same requirement for a vehicle that is being chained up for winter storms is replaced with a requirement that the vehicle display flashing hazards lights or warning lights when chaining up.

- Bill C – Yielding to larger vehicles in roundabouts. The bill requires a driver to yield the right-of-way to a driver of a vehicle having a total length of at least 40 feet or a total width of at least 10 feet (large vehicle) when driving through a roundabout. The bill also requires that when 2 drivers of large vehicles approach or drive through a roundabout at the same time, the driver on the right must yield the right-of-way to the driver on the left.

A person who fails to yield commits a class A traffic infraction and is subject to a fine of $70 and an $11 surcharge.

- Bill D – Education requirements associated with the licensing of a minor to drive a motor vehicle on a roadway. For 10 years, the bill creates a refundable income tax credit for purchasing driver education and training for a minor. The amount of the credit is the amount spent on driver education and training, but cannot exceed $1,000 per student. To claim a credit, an individual must provide the Department of Revenue with a receipt for the amount paid if the department requests the receipt.

The bill replaces the current driver’s education requirements for a minor who is under 18 years of age to be issued a driver’s license with requirements that the minor:

-

- Complete a 30-hour driver education course, which may include an online course, approved by the department; and

- Receive at least 6 hours of behind-the-wheel driving training with a driving instructor or, for minors who live in rural areas of the state, 12 hours of behind-the-wheel training with a parent, a legal guardian, or an alternate permit supervisor.

The bill adds a requirement that a minor who is 18 to 21 years of age must successfully complete a 4-hour prequalification driver awareness program to be issued a driver’s license.

A person who has been convicted of certain violent or sexual crimes is prohibited from providing behind-the-wheel driving instruction to minors. A commercial driving school is prohibited from employing such a driving instructor to provide behind-the-wheel driving instruction to minors. Each instructor employed by a commercial driving school must obtain a fingerprint-based criminal history record check to verify that the instructor has not committed a disqualifying crime.

- Bill E – The enforcement of safety requirements for intrastate motor vehicle carriers. The bill changes the amount of civil penalties that may be levied on commercial motor carriers for failure to comply with rules for the safe operation of commercial vehicles by tying the amount of civil penalties to the amount of federal civil penalties for interstate commercial motor carriers.

The bill also authorizes the department of revenue to cancel or deny registration of a commercial motor carrier that fails to cooperate with the completion of a safety compliance review within 30 days.

Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning the Treatment of Persons with Behavioral Health Disorders in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Systems

The Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning the Treatment of Persons with Behavioral Health Disorders in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Systems (BHDCJS) met four times during the 2022 interim. The committee heard presentations from multiple stakeholders, behavioral and mental health advocates, and representatives from state executive departments concerning the issues facing persons with behavioral health disorders who have been in contact, in one form or another, with the criminal or juvenile justice systems.

The committee requested seven bills to be drafted. Of those, two were withdrawn prior to the September 29, 2022, meeting, and one was withdrawn at that meeting. The following four bills were recommended by the committee to the Legislative Council for consideration:

- Bill A – Concerning issues related to juvenile competency to proceed. The bill addresses issues related to a determination of juvenile competency to proceed (competency) and restoration of competency (restoration). The bill allows:

- The district attorney, defense attorney, guardian ad litem, department of human services, a competency evaluator, a restoration treatment provider, and the court, without written consent of the juvenile or further order of the court, to access competency evaluations and restoration evaluations, including all second evaluations; information and documents related to competency evaluations; the competency evaluator, for the purpose of discussing the competency evaluation; and the providers of court-ordered restoration services for the purpose of discussing such services;

- Parties to exchange names, addresses, reports, and statements of physicians or psychologists who examined or treated the juvenile for competency;

- The court or any party to raise, at any time, the issue of a need for a restoration evaluation of the juvenile’s competency; and

- A juvenile to be examined by a competency evaluator of the juvenile’s own choice and to request a second evaluation in response to a court-ordered competency evaluation or a court-ordered restoration evaluation.

If the court determines that the juvenile is incompetent to proceed and unlikely to be restored to competency in the reasonably foreseeable future, a time frame is set forth for the dismissal of charges based on the severity and type of charge.

- Bill B – Concerning ongoing funding for the Colorado 911 resource center. To provide ongoing funding for the Colorado 911 resource center, the state treasurer is required to issue a warrant, paid from the general fund, in the amount of $250,000 to the Colorado 911 resource center on July 1, 2023, and on each July 1 thereafter.

- Bill C – Concerning prior authorization exemption for medicaid coverage of medications treating serious mental illness. The bill prohibits the department of health care policy and financing from imposing prior authorization, step therapy, and fail first requirements for medicaid coverage of a prescription drug, as indicated on federally approved labels, to treat serious mental health disorders.

- Bill D – Concerning measures to regulate the use of restrictive practices on individuals in correctional facilities. The bill prohibits the use of a clinical restraint on an individual, unless:

- The use is to prevent the individual from committing imminent and serious harm to the individual’s self or another person, based on immediately present evidence and circumstances;

- All less restrictive interventions have been exhausted; and

- The clinical restraint is ordered by a licensed mental health provider.

The bill requires facilities that utilize clinical restraints to implement procedures to ensure frequent and consistent monitoring for the individual subjected to the clinical restraint and uniform documentation procedures concerning the use of the clinical restraint.

The bill limits the amount of time an individual may be subjected to a clinical restraint per each restraint episode and within a calendar year.

The bill prohibits the use of an involuntary medication on an individual, unless:

-

- The individual is determined to be dangerous to the individual’s self or another person and the treatment is in the individual’s medical interest;

- All less restrictive alternative interventions have been exhausted; and

- The involuntary medication is administered after exhaustion of procedural requirements that ensure a hearing, opportunity for review, and right to counsel.

The bill requires the department of corrections (department) to submit an annual report to the judiciary committees of the senate and house of representatives with data concerning the use of clinical restraints and involuntary medication in the preceding calendar year.

The bill requires the department to include specific data concerning the placement of individuals in settings with heightened restrictions in its annual administrative segregation report.

Water Resources and Agriculture Review Committee

The Water Resources and Agriculture Review Committee (WRARC) met three times during the interim and heard testimony from various water stakeholders in the state. On August 4, 2022, the WRARC asked requested 11 bills to be drafted to address various subject matters relating to water issues in the state. However, by the time the committee met on September 22 to select which bill drafts to advance for the consideration of the Legislative Council, nine of those requests were withdrawn. As a result, the WRARC voted to advance only the following two bills:

- Bill A – Task Force on High-altitude Water Storage creates a task force to study the feasibility of implementing water storage in the form of snow in high-altitude areas of the state (task force). The task force must submit a report to the WRARC on or before June 1, 2024, which report:

- Describes the feasibility of implementing high-altitude water storage in Colorado;

- Describes findings and recommendations regarding issues considered by the task force; and

- Describes any legislative proposals associated with the implementation of high-altitude water storage in Colorado, including identification of any state agencies that will be responsible for implementing legislative directives and identification of funding sources.

The task force is repealed, effective December 1, 2024.

- Bill B – Water Resources & Agriculture Review Committee converts the WRARC from an interim committee to a committee that may meet year-round. The bill also strikes obsolete language, removes limitations on the number of meetings and the number of field trips the WRARC may hold, and requires the WRARC to meet at least four times during each calendar year.

Wildfire Matters Review Committee

The Wildfire Matters Review Committee (WMRC) met five times during the 2022 interim and took one field trip. On September 28, 2022, the WMRC voted to advance the following five bills to the Legislative Council:

- Bill A – Forestry and Wildfire Mitigation Workforce. The bill directs the Colorado state forest service (state forest service) to develop educational materials for high school students relating to career opportunities in forestry and wildfire mitigation. The bill also creates the timber, forest health, and wildfire mitigation industries workforce development program, which provides partial reimbursement to timber businesses and other related entities for the costs of hiring interns. The bill also authorizes the expansion and creation of forestry programs in the community college system and at Colorado mountain college. Finally, the bill directs the state board for community colleges and occupational education to increase the number of qualified educators at certain colleges that deliver wildfire prevention and mitigation programs.

- Bill B – Wildfire Detection Technology Pilot Program. The bill requires the center of excellence for advanced technology aerial firefighting in the division of fire prevention and control (division) in the department of public safety to establish one or more remote camera technology pilot programs.

- Bill C – Timber Industry Incentives. The bill creates the timber, forest health, and wildfire mitigation industries workforce development program in the state forest service, which provides partial reimbursement to timber businesses and other related entities for the costs of hiring interns. The bill also creates an income tax credit for tax years 2023 through 2027 for timber businesses and other related businesses.

- Bill D – Updates To State Forest Service Tree Nursery. The bill requires the state forest service to make certain upgrades and improvements to its seedling tree nursery.

- Bill E – Fire Investigations. The bill directs the director of the division to report on the investigation of wildland fires in the state and creates the fire investigation fund to fund fire investigations.

-

2022 Interim Committee Recap – Part 1

Several legislative interim committees have been holding public meetings since the end of the last legislative session to discuss topics relevant to Colorado and to recommend legislation to the Legislative Council committee for approval for introduction in 2023. This week, we’re providing a

summary of each of committee and its recommended legislation. The Legislative Council met on Friday, October 14, to review interim committee legislation proposals. Click here to listen to the meeting.

summary of each of committee and its recommended legislation. The Legislative Council met on Friday, October 14, to review interim committee legislation proposals. Click here to listen to the meeting.For more information about interim committees generally and how they operate, see “Interim Committees: Just the Facts, Ma’am”, posted July 21, 2017.

Colorado Youth Advisory Council Review Committee

The Colorado Youth Advisory Council Review Committee met three times during the interim. The committee heard presentations from its student members about discipline in public schools, completing financial aid applications, increasing the number of school psychologists, substance use, educational standards, eating disorders, weight discrimination, and youth sexual health. The committee requested the drafting of three bills. The committee recommended all three bills to the Legislative Council.

- Bill A – Disordered Eating Prevention. The bill creates the Office of Disordered Eating Prevention (office) in the Department of Public Health and Environment (department). The bill requires the office and the department to:

- Create a resource bank for research and resources for treatment and services;

- Collaborate with the Office of Suicide Prevention, the Behavioral Health Administration, and organizations within the healthcare industry to close gaps in care and provide support for individuals with disordered eating transitioning out of inpatient care;

- Create outreach resources educating youth on how to seek care for disordered eating;

- Partner with the Department of Education to inform teachers, administrators, school staff, and parents on disordered eating prevention and treatment;

- Coordinate the Disordered Eating Prevention Research Grant Program; and

- Prepare written information for primary care offices and providers throughout the state.

The bill also creates the Disordered Eating Prevention Commission (commission) in the department consisting of seventeen members that have a personal connection to disordered eating prevention. The purpose of the commission is to provide leadership on disordered eating prevention in Colorado; set statewide data-driven, evidence-based, and clinically informed priorities for disordered eating prevention; serve as the advisor to the office of disordered eating prevention; provide a forum for government agencies, lawmakers, and community members to examine the current status of disordered eating prevention policies; provide a voice for youth on issues impacting youth; and provide forums for diverse perspectives and communities for support and information.

The bill further creates the Disordered Eating Prevention Research Grant Program (grant program) in the department. The purpose of the grant program is to provide financial assistance to eligible applicants to conduct research on risk factors for disordered eating, the impact disordered eating has on Colorado, or public interventions that examine and address the root causes of disordered eating.

- Bill B – Secondary School Student Substance Use. The bill creates the Secondary School Student Substance Use Committee (committee) in the Department of Education (department) to develop a practice or identify or modify an existing practice for secondary schools to implement that identifies students in need of treatment for substance use, offers a brief intervention, and refers students to substance use treatment resources. The bill requires the department to publish a report of the committee’s findings and submit the report to the superintendent of every school district and the chief administrator of every institute charter school that is a secondary school.

- Bill C – Disproportionate Discipline in Public Schools. The bill requires each school district board of education, institute charter school board, or governing board of a board of cooperative services (BOCES) to adopt a policy to address disproportionate disciplinary practices in public schools. Each school entity must develop, implement, and annually review improvement plans if the data reported to the Department of Education shows disproportionate discipline practices at the local education provider. Each provider shall provide to the parents of students enrolled in the school written notice of the improvement plan and issues identified by the local education provider. The bill requires school districts to consider certain factors before suspending or expelling a student. The bill requires school districts to document in a student’s record and compile in the Safe School report any alternative disciplinary attempts before suspending or expelling a student.

Legislative Interim Committee on Judicial Discipline

The Legislative Interim Committee on Judicial Discipline met five times during the 2022 interim to examine Colorado’s judicial discipline system, including the topics outlined in Senate Bill 22-201. The committee heard presentations from Colorado’s Judicial Department, the Colorado Commission on Judicial Discipline, and experts in the field of judicial discipline, and the committee heard public testimony at each of its first four meetings. The committee requested the drafting of two bills and one resolution. Of those, one bill was withdrawn at the September 30, 2022, meeting and the other two pieces of legislation were recommended by the committee to the Legislative Council for its consideration.

- Bill A – Submitting to the Registered Electors of the State of Colorado an Amendment to the Colorado Constitution Concerning Judicial Discipline. The concurrent resolution amends section 23 of article VI of the Colorado Constitution as it relates to judicial discipline. The resolution clarifies the commission on judicial discipline’s (commission) duties and authority. The resolution repeals the authority of the commission and special masters to conduct formal judicial disciplinary proceedings and creates an independent adjudicative board (board) to conduct formal proceedings and hear appeals of the commission’s orders imposing informal sanctions. A panel of the board may dismiss a complaint, impose informal sanctions, or impose formal sanctions. The resolution sets the standards of review to be used by the supreme court when it reviews a panel’s decision and requires a tribunal of seven randomly selected court of appeals judges to review a panel’s decision in cases involving a Colorado supreme court justice, a staff member to a justice, or a family member of a justice, or when more than two justices have recused themselves from the proceeding. The resolution requires judicial discipline proceedings be made public at the commencement of formal proceedings. The resolution clarifies the circumstances in which the commission may release otherwise confidential information. Finally, the resolution creates a rule-making committee to propose rules for the commission. The supreme court approves or rejects each rule proposed by the rule-making committee.

- Bill B – Judicial Discipline. The bill establishes rule-making procedure for rules governing the commission on judicial discipline (commission) and judicial discipline adjudicative board (board) proceedings. The bill also clarifies who provides administrative staff support for board proceedings. The bill permits a person to submit a request for evaluation of judicial misconduct by mail or online and also permits a person to submit a confidential or anonymous request for evaluation. The bill establishes a process for the office of judicial discipline to provide complainants with information about the judicial discipline process and about the status of the complainant’s request and any subsequent investigation and disciplinary or adjudicative process. The bill requires the commission include certain information in its annual report and make the information available online. The bill repeals the statute establishing the legislative interim committee on judicial discipline because the committee is not authorized to meet after the 2022 legislative interim.

Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning Tax Policy

The Legislative Oversight Committee Concerning Tax Policy met four times during the interim. The committee heard presentations on severance taxes, sales and use taxation of services, national perspectives on property taxes, and collecting excise tax from delivery sellers under House Bill 20-1427. Additionally, the state auditor’s office presented tax expenditure evaluations. The committee also set the scope of tax policies to be considered by its subordinate Task Force Concerning Tax Policy to include applying state income tax to federal adjusted gross income and options for expanding sales and use tax to apply to services.

The committee requested nine bills for drafting and recommended five to the Legislative Council for introduction:

- Bill A – Repeal of Infrequently Used Tax Expenditures. The bill eliminates ten infrequently used income tax exemptions, deductions, and credits.

- Bill B – Taxation of Tobacco Products. The bill categorizes transactions involving tobacco products other than smokeless and roll-your-own tobacco products as remote retail sales rather than delivery sales and establishes a system for taxation and licensing of such sales that mirrors the current system for delivery sales.

- Bill C – Tax Credits for Low- and Middle-income Working Individuals or Families. The bill increases the state earned income tax credit to 40% of the federal credit claimed, increases the percentages of the federal credit that can be claimed for the state child tax credit depending on income level, and increases the age of an eligible child for the child tax credit from under six years old to under 18 years old.

- Bill D – Long-term Care Insurance Tax Credit. The bill increases the amount of federal taxable income that qualifies for the credit and doubles the amount of credit that may be claimed.

- Bill E – Unauthorized Insurance Premium Tax Rate. The bill increases the unauthorized insurance premium tax rate to three percent in parity with the surplus lines insurance premium tax rate.

Pension Review Commission and Pension Review Subcommittee

The Pension Review Commission (commission) met twice during the interim. It heard presentations from the Fire and Police Pension Association (FPPA) and the Public Employees’ Retirement Association (PERA). In addition, the commission heard proposals for legislation from its own Pension Review Subcommittee. The Pension Review Subcommittee itself met three times to: (1) Hear presentations regarding House Bill 22-1029 – Compensatory Direct Distribution to PERA and the Direct Distribution to PERA; (2) Discuss proposed legislation and questions to be submitted to PERA; (3) Hear from PERA regarding answers to their submitted questions; and (4) Discuss its annual reports to the General Assembly and the citizens of Colorado.

The Pension Review Commission requested that three bills be drafted and ultimately recommended one bill to the Legislative Council for introduction as follows:

- Bill A – Temporary Tax Credit for Public Service Retirees. Although the bill as originally requested and drafted increased the pension or annuity income tax deduction, the commission amended the bill in committee to create an income tax credit for public service retirees. The bill creates an income tax credit for income tax years commencing on or after January 1, 2023, but prior to January 1, 2025, for a qualifying public service retiree. A “public service retiree” means a full-time Colorado resident individual who is 55 years of age or older at the end of the 2023 or 2024 income tax year and who is a retiree of a Colorado public pension plan administered pursuant to the Colorado Revised Statutes or a retiree of a public pension plan administered by a local government of the state of Colorado.

Sales and Use Tax Simplification Task Force

The Sales and Use Tax Simplification Task Force met four times during the interim. It heard presentations from the Colorado Department of Revenue, the Colorado Counties Inc. (CCI), the Colorado Municipal League (CML), local government representatives, and private industry stakeholders. A general discussion relating to the SUTS system, the retail delivery fee, Colorado sale and use taxes, including taxes on construction materials through the building permit process, the simplification of the state sales return, and local lodging taxes with an opportunity for public comment occurred. In addition, the task force heard an overview of the Wayfair v. Lakewood complaint and sales and use tax expenditure evaluation reports from the Office of the State Auditor.

The task force requested that four bills and one resolution be drafted and ultimately recommended one bill and one resolution to the Legislative Council for introduction as follows:

- Resolution A – Uniform Sales & Use Tax on Construction Materials. Resolution A urges municipalities that locally collect their taxes to cooperate on a uniform administration of sales and use tax on construction materials, to standardize information on building permits, and to speed up the issuance of certain documentation. It also requests that the Colorado Municipal League update the task force on these efforts.

- Bill B – Electronic Sales & Use Tax Simplification System. The electronic sales and use tax simplification system (SUTS) is a one-stop portal designed to facilitate the collection and remittance of sales and use tax. For the purpose of improving the system, the bill requires the department to make certain changes to the system and permits it to make others. It also prohibits the department from imposing certain convenience fees for payments through SUTS and requires the department to promote SUTS for the purpose of increasing the awareness, participation, and compliance by retailers and local taxing jurisdictions.

- Bill A – Disordered Eating Prevention. The bill creates the Office of Disordered Eating Prevention (office) in the Department of Public Health and Environment (department). The bill requires the office and the department to:

-

Mark Your Calendars, Session Starts on Monday, January 9, 2023.

By Ed DeCecco

With all due respect to The Mamas and Papas, Monday is a fine day of the week too. Yes, we sometimes get a little sad on Sunday night anticipating it, and of course Friday is objectively better. Still, the word is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word Mōnandæg, which loosely means “the moon’s day,” and the moon is awesome. Plus, there is Monday Night Football, and there is an internet myth that it is the least likely day of the week to have rain, and … wait, I can’t do this. I’ve tried to be cheerful, but I’m with the majority of the rest of the world—Mondays kind of stink!

Or at least they usually do, but Monday, January 9, 2023, is certainly an exception. On that date, the 74th General Assembly of the State of Colorado will convene its First Regular Session.

The reason session is starting on a Monday is a combination of constitutional provisions. Section 1 of article IV of the state constitution requires the newly elected Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, Treasurer, and Secretary of State to take office on the second Tuesday of January, which this year falls on January 10, 2023. And section 3 of article IV of the state constitution requires the election returns for these officers to be transmitted to the Speaker of the House, “who shall immediately, upon the organization of the house, and before proceeding to other business, open and publish the same in the presence of a majority of the members of both houses of the general assembly, who shall for that purpose assembly in the house of representatives.” Under section 3, members of both houses are also required to decide the winners if the general election ends in a tie or is contested. To ensure the statewide officers can take office in a timely manner and to comply with its constitutional duties, the General Assembly must convene earlier than the second Tuesday in January.

The reason session is starting on a Monday is a combination of constitutional provisions. Section 1 of article IV of the state constitution requires the newly elected Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, Treasurer, and Secretary of State to take office on the second Tuesday of January, which this year falls on January 10, 2023. And section 3 of article IV of the state constitution requires the election returns for these officers to be transmitted to the Speaker of the House, “who shall immediately, upon the organization of the house, and before proceeding to other business, open and publish the same in the presence of a majority of the members of both houses of the general assembly, who shall for that purpose assembly in the house of representatives.” Under section 3, members of both houses are also required to decide the winners if the general election ends in a tie or is contested. To ensure the statewide officers can take office in a timely manner and to comply with its constitutional duties, the General Assembly must convene earlier than the second Tuesday in January.Luckily, the General Assembly has some flexibility on when it starts. Section 7 of article V of the state constitution requires the General Assembly to meet in regular session at 10 a.m. “no later than the second Wednesday of January each year.” Thus, the General Assembly will start on the second Monday of January, instead of the second Wednesday, which is the default start date.

When this last occurred in the 2019 legislative session, the General Assembly adopted House Joint Resolution 18-1021 to set the convening date on the Friday prior to the second Tuesday and to make related changes to the deadlines set forth in Joint Rules 23 and 24. It then passed another resolution in 2019 to restore the deadlines after the session to their prior form.

While everyone enjoys a two-for-one deal when it is a BOGO at King Soopers, it is less appealing with legislation. So this time around, the General Assembly adopted House Joint Resolution 22-1025, which created Joint Rule 22A to establish alternative deadlines that only apply for the 2023 legislative session. This rule only applies for this session, and it repeals on January 1, 2024. Joint Rule 23 and other related rules will apply again thereafter, or at least they’ll apply until the next time the General Assembly has to create a one-time rule to address this type of situation, which will be in 2027.

An early convening date means earlier bill request deadlines. This year, each returning legislator must submit three of their five bill requests to the Office of Legislative Legal Services (OLLS) no later than November 29, 2022. Each legislator who is newly elected to the General Assembly must submit three of their five bill requests to the OLLS no later than December 13, 2022. Both of these dates are a few days earlier than usual. A number of other deadlines have also been slightly altered, and you can find those deadlines in House Joint Resolution 22-1025, or in this handy document.

One deadline that is not included in the resolution or rules but that warrants mention is sine die. Under section 7 of article V of the Colorado Constitution, sessions are limited to 120 days in length, and in most years, the General Assembly uses all of its allotted time. If that is the case again in 2023, then, barring any unforeseen circumstances,[1] the General Assembly will adjourn on Monday, May 8, 2023. So now we have at least two Mondays to look forward to in 2023!

______________________________________________________________________

[1] The author has assured the LegiSource Board that he vigorously knocked on wood after typing this sentence, so as to avoid the cosmic response of an increased likelihood in 2023 of the application of Joint Rule 44 (g), which applies to the counting of legislative days during a temporary adjournment during declared disaster emergency.

-

New Water Demand Management Agreement on the Colorado River (Updated)

by Thomas Morris

Editor’s note: This article was originally posted September 19, 2019. We are reposting it on September 22, 2022 with updated information.

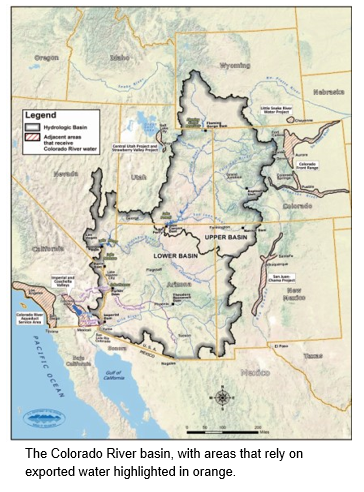

What happens when the demand for a commodity exceeds supply? Economic theory predicts that the price for the commodity will increase. We’re all aware that water in Colorado is relatively scarce; in particular, the northern Front Range is highly dependent on water imported from the Colorado River, which is subject to increasing demands and dwindling supply. Are increases in the price of water sufficient to address this deficit?

As we’ll see, due to multiple layers of state, interstate, and federal law and a combination of climate change effects, prolonged drought, and demand increases, our Colorado River water supply is at risk, and more is required to avoid fairly serious adverse consequences than simply relying on the market to equalize the supply and demand for water.

The law of the river. The use of Colorado River water is strictly governed by the so-called “law of the river,” which is a complex interplay of interstate compacts, federal statutes and regulations, United States Supreme Court decrees, and applicable state law.

The law of the river. The use of Colorado River water is strictly governed by the so-called “law of the river,” which is a complex interplay of interstate compacts, federal statutes and regulations, United States Supreme Court decrees, and applicable state law.To avoid having California’s rapid growth gobble up available Colorado River supplies, in 1922 the seven states in the Colorado River basin[1] entered into an interstate compact. The Colorado River Compact (codified in article 61 of title 37, C.R.S.) allocated 7.5 million acre-feet[2] (Maf) of water per year to the upper basin states (including Colorado) and 8.5 Maf to the lower basin states, for a total 16 Maf.[3] Later, the upper basin states entered into the Upper Colorado River Compact (codified in article 62 of title 37, C.R.S.), pursuant to which 51.75% of the upper basin’s supplies were allocated to Colorado.

Naturally, the states presumed that the river’s supplies were adequate, even plentiful, to meet these allocations. Indeed, from 1905 to 1921 the flow at the boundary between the upper and lower basins was about 18 Maf. Unfortunately, the 1922 compact was negotiated during a time of relatively high flows: rather than more than 16 Maf of flow per year, actual supplies under current conditions may be as low as 14.8 Maf. Moreover, climate change is likely to reduce this supply even more:

Colorado River flows decline by about 4 percent per degree Fahrenheit increase . . . . Thus, warming could reduce water flow in the Colorado [River] by 20 percent or more below the 20th-century average by midcentury, and by as much as 40 percent by the end of the century.[4]

Despite this somewhat grim outlook, the upper basin’s ability to comply with its delivery obligation to the lower basin is enhanced by two facts:

- The 1922 compact states the delivery obligation as 75 Maf over 10 years rather than 7.5 Maf each year; and

- Numerous reservoirs with significant storage capacities are located in the upper basin. These reservoirs, including Lake Powell[5] and several reservoirs referred to as the Aspinall Unit, store excess supplies in wet years and release them in dry years to comply with the delivery obligation.

Staving off a shortage declaration through demand management. The federal Bureau of Reclamation operates the Aspinall Unit as well as Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which is the lower basin’s primary reservoir. Pursuant to an agreement[6] between the seven compacting states, the bureau operates the Aspinall Unit and Lakes Powell and Mead to maintain the water level in Lake Mead above 1,075 feet in elevation. If the water drops to that level, the bureau makes a “shortage declaration” that triggers mandatory restrictions on water diversions and usage in the lower basin. A shortage declaration may also be the first step toward a determination that the upper basin has failed to comply with its delivery obligation, which would result in the curtailment of upper basin diversions that postdate the 1922 compact.

In order to reduce the risk of a shortage declaration occurring, the upper and lower basins have both recently adopted updated drought contingency plans.[7] Congress has approved the plans.[8]

In particular, the upper basin’s drought contingency plan involves three elements:

- Augmentation, consisting of weather modification efforts to increase precipitation and the removal of phreatophytes (plants that have deep root systems that draw water from near the water table and often consume an unusually large amount of water);

- Operating the Aspinall Unit to benefit storage in Lake Powell; and

- Demand management.

Demand management in this context means, roughly, a temporary, voluntary, and compensated reduction in consumptive water use by specific water rights owners. In Colorado, demand management could involve a front range metropolitan water provider (whose water rights postdate the 1922 decree and thus whose diversions would be curtailed if the upper basin failed to meet its delivery obligation) paying a senior agricultural user on the western slope to temporarily not divert water from the Colorado River or its tributaries. The metropolitan water provider would then be able to continue to export Colorado River water to its Front Range water users. As the saying goes, water flows uphill toward money.

The General Assembly recently supported the development of demand management programs by enacting SB 19-212. The bill appropriates $1.7 million from the general fund to the department of natural resources for use by the Colorado Water Conservation Board. The board will use this money for stakeholder outreach and technical analysis to develop a water resources demand management program.

The days of hoping that Colorado River supplies will somehow recover or that the lower basin will, by some miracle, substantially reduce its water consumption enough to avoid a shortage declaration are over. Colorado is preparing for a hotter, drier climate in which water demands continue to increase while supplies diminish. Water demand management is one of the primary tools (along with conservation and the development of additional storage) that will be used to adapt to this new normal.

In the article originally posted in 2019, the author posed the question “Are increases in the price of water sufficient to address this [water] deficit?” Following is an update that suggests the answer to this question is a resounding “no”, as the Colorado River water supply continues to dwindle.

UPDATE:[9] On August 16, 2022, the Bureau of Reclamation within the federal Department of the Interior released its “Colorado River Basin August 2022 24-Month Study”, which sets the annual operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead in 2023 in light of critically low reservoir conditions. The key findings include:

UPDATE:[9] On August 16, 2022, the Bureau of Reclamation within the federal Department of the Interior released its “Colorado River Basin August 2022 24-Month Study”, which sets the annual operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead in 2023 in light of critically low reservoir conditions. The key findings include:Lake Powell’s water surface elevation on January 1, 2023, is projected to be 3,522 feet, which is 178 feet below full (3,700 feet) and only 32 feet above the minimum level required in order to continue to produce power at Glen Canyon Dam (3,490 feet). The Department of the Interior will limit 2023 releases from Lake Powell in order to protect it from declining below 3,525 feet at the end of December 2023. The Department will also evaluate hydrologic conditions again in April 2023.

Lake Mead’s water surface elevation on January 1, 2023, is projected to be 1,047.61 feet, which reflects an unprecedented shortage condition that requires shortage reductions and water savings contributions from the Lower Basin States and Mexico, as follows:[10]

-

- Arizona: 592,000 acre-feet, which is approximately 21% of the state’s annual apportionment;

- Nevada: 25,000 acre-feet, which is 8% of the state’s annual apportionment; and

- Mexico: 104,000 acre-feet, which is approximately 7% of the country’s annual allotment.

There is no required water savings contribution for California in 2023 under the current operating condition.

The Department and the Bureau of Reclamation continue to share and update information concerning the increasing risks impacting Lake Powell and Lake Mead. For more information, visit https://www.doi.gov/news.

_________________________________________________________________

[1] The seven states of the Colorado River Basin are Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. The upper basin consists mainly of Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah; New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California are mainly in the lower basin.

[2] An acre-foot is the amount of water required to cover one acre to a depth of one foot. An acre is about the size of a football field, including both end zones.

[3] For comparison, Colorado consumes about 5.3 Maf per year, but this includes water that has been reused multiple times. See the state water plan, Figure 5-1. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cowaterplan/plan

[4] http://theconversation.com/climate-change-is-shrinking-the-colorado-river-76280

[5] Lake Powell is located directly above the boundary between the upper and lower basins; releases from Lake Powell are the primary method by which the upper basin complies with the 1922 compact.

[6] Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead”, 72 FR 62272 (11/2/07); https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-11-02/pdf/E7-21417.pdf

[7] Agreement Concerning Colorado River Drought Contingency Management and Operations; https://www.usbr.gov/dcp/docs/final/Companion-Agreement-Final.pdf

[8] Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan Authorization Act; https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr2030/BILLS-116hr2030enr.pdf

[9] This update was prepared by the LegiSource board, not the original author.

[10] These reductions and contributions are required pursuant to the 2019 Drought Contingency Plans and Minute 323 to the 1944 U.S. Mexico Water Treaty.