by Sarah Meisch

Colorado’s State Lines

In Part 1 of this series, we explored how the US created its states, prioritizing geometric simplicity over geographical variance. Colorado stands uniquely symmetrical and rectangular among other states, and Part 2 of this series will examine how Colorado’s shape and dimensions were placed – and why its borders have been so controversial.

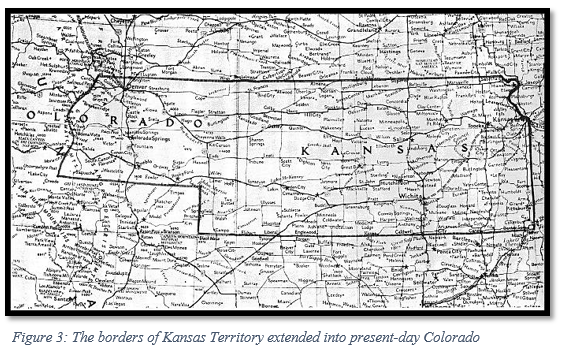

Throughout its history, Colorado has been under the control of France, Spain, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, and the US. The Rocky Mountains formed a natural barrier between the American-owned Louisiana Purchase lands and the area belonging to Spanish Mexico. What would become the western and southern parts of Colorado were acquired by the US government through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Before the Anglo population grew in Colorado, the land was occupied by several indigenous tribes, including the Ute, Jicarilla Apache, Arapaho, Anasazi, Navajo, Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Pueblo, and Shoshone. Many of these tribes were forced to consolidate or give up their land when white settlers moved into the region. When Kansas Territory was created in 1854, most of central Colorado and the eastern plains were absorbed into Kansas; the parts of Colorado that lay west of the Rocky Mountains had become part of Utah Territory in 1850.

Following the Pike’s Peak gold rush of 1858-1860, the Front Range and foothills of the Rocky Mountains became more heavily populated, with most of the growth attributed to young and single male miners. The population would diminish over the following years as the spoils of the gold rush faded and the lawlessness of the region made the area unsettling for young families.

With Kansas Territory’s capital being in eastern Kansas, inhabitants of present-day Colorado began to wish for a closer form of government, as well as more locally-enforced law enforcement of the region. In November 1858, Denver residents elected a delegate to the US Congress to officially request that Congress create a new territory.

Colorado’s request was particularly troublesome, as the territorial population was strongly Republican, and Southern Democrats were concerned they would not find support in the area. In the heat of deadlock over the slavery debate, Congress would refuse to act on this request until 1861.

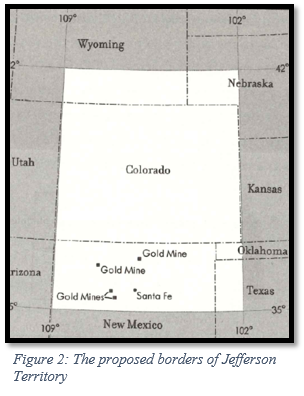

In 1859, Colorado residents decided to take matters into their own hands and, without congressional approval, formed Jefferson Territory, named after the president who had overseen the Louisiana Purchase. For a year and a half, the territory illegitimately elected officials, created territorial boundaries, and established a legislature that adopted legislation related to personal and civil rights. The enlarged borders of Jefferson Territory would have made Colorado about 70% larger than it is today and would have included areas within Wyoming, Nebraska, Utah, and Kansas. This additional land would have contained much of the gold and silver of the region for mining and would also have brought the territory agricultural land, diversifying the economy of the territory from relying entirely on mineral resources. Geographically centering the Rocky Mountains within Jefferson Territory, rather than placing the mountains at the borders, would also “prevent disputes over profitable mining claims.”[1]

Creating a provisional territory was not unusual. Other parts of the country had instituted provisional governments until Congress officially recognized territorial governments: Deseret became Utah and the State of Franklin became Tennessee. Jefferson Territory adopted a similar extralegal approach until Congress had established an official territory.

A census found that Colorado was occupied by only 34,277 residents in 1860, making it too small to be a state but large enough for another structure of government. And most Colorado voters refused to vote for statehood when they had the opportunity in 1864, due to the higher taxation associated with new statehood. As a territory, the federal government footed the bills; however, this made the extralegal entity of Jefferson Territory unable to collect taxes from residents.

Jefferson Territory ceased to exist when Congress and President Buchanan created the Colorado Territory on February 28, 1861. Members of Congress opposed naming states and territories after individuals, so the name Jefferson was dropped. Although some legislators favored naming the new territory “Idaho,” the delegate from Colorado successfully convinced legislators that “Colorado” would be a more fitting name, as the Colorado River started within the territory. Jefferson County is the sole remaining county from Jefferson Territory.

In the 1860s, there were several attempts by residents to make Colorado a state, but with Civil War and Reconstruction era policies dividing up the political scene in Washington, Colorado was not admitted as a state until 1876.[2]

The Borders of Colorado

The eastern border of Colorado was determined by Kansas’ western border when Kansas achieved statehood in 1861, only a month before Colorado Territory was created. A contentious statehood debate raged over the possibility of a “Big Kansas,” which would have included large swaths of Nebraska and possibly areas of Colorado that had already been part of Kansas Territory. Some Kansans raised concerns over how the population of the mining areas in Colorado would upset the balance of power in Kansas. During the 1859 Wyandotte constitutional convention in Kansas, some local delegates claimed that eastern and western Kansas Territory varied too widely in culture and politics or that the Kansas government was too far away from the mining areas of Colorado to provide much responsiveness; linking these areas permanently in statehood would raise the potential for conflict. Others were concerned with the cost of having such a large state, with Republican delegate and future Kansas congressman M.F. Conway stating, “Had we retained the Pike’s Peak region, the mere mileage of the members of the Legislature and officers going to and returning from the State capital would more than exceed the cost of the whole State government.” Political divisions were clear on the matter, as “many Democrats opposed the exclusion of the western territory, while many Republicans approved of the rejection.”[3]

The arguments for keeping part of present-day Colorado with Kansas were resource-driven. Some wanted the wealth of the mining industry in the Rockies to flow to Kansas, and others believed that the railroad builders would look favorably upon investing in Kansas with its connections to Colorado mineral resources. A few members of the convention argued that cutting off the Rockies and their mining settlements would bring the population of Kansas down to a point where statehood would be off the table, as territories needed to cross a certain population threshold to become a state.

In 1859, the Wyandotte constitutional convention agreed with the “Little Kansas” proponents, which gave the state of Kansas its current size. Creating a homogenous Kansas and allowing the miners to create a government for their region was well-received in both Colorado and Kansas.

When Colorado residents, including many miners, drew the boundaries for the extralegal Jefferson Territory, the same line was drawn with Kansas, exemplifying inhabitants’ agreement with Kansas’ proposed boundary line. Kansas became a state in 1861, solidifying the boundaries voted on in the Wyandotte constitution.

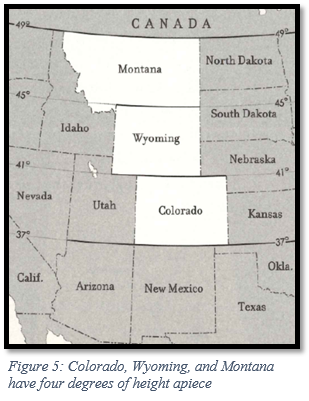

Congress drew Colorado’s western borders according to the equitable principles outlined in Part 1, and with the western landscape largely open, Congress had a chance to make border divisions as equal as possible. The prairie states of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas all have three latitudinal degrees of height. Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana have four latitudinal degrees of height – the extra degree, given out of fairness, allows for the less arable agricultural land these states share. Colorado, Wyoming, the Dakotas, Oregon, and Washington also have nearly seven longitudinal degrees of width per state. This was intentionally done to promote border equality in the western states. Therefore, the western border Colorado shares with Utah was drawn to give the state seven longitudinal degrees of width from the border with Kansas.

The northern border of Colorado was initially proposed to be drawn at the 42nd parallel, aligning with a 1790 agreement called the Nootka Convention, which was signed between England and Spain as a way of dividing their interests in western North America. This line currently provides borders for Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah.

However, Congress wanted to ensure that four longitudinal degrees of height in Colorado were observed, so the northern border was lowered by a degree, as the southern border with New Mexico Territory had already been loosely planned in 1850. This allowed Wyoming and Montana to have four longitudinal degrees of height when they became states years later.

The northern border of Colorado was initially proposed to be drawn at the 42nd parallel, aligning with a 1790 agreement called the Nootka Convention, which was signed between England and Spain as a way of dividing their interests in western North America. This line currently provides borders for Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah. However, Congress wanted to ensure that four longitudinal degrees of height in Colorado were observed, so the northern border was lowered by a degree, as the southern border with New Mexico Territory had already been loosely planned in 1850. This allowed Wyoming and Montana to have four longitudinal degrees of height when they became states years later.

Colorado’s southern border with New Mexico was largely determined by the territorial acts of Utah and New Mexico in 1850 and has been rooted in controversy and violence. Colorado residents initially lobbied for Jefferson Territory to include northern New Mexico. There were several gold mines in the north central part of New Mexico Territory, and Coloradans wanted access to as much gold as possible to sustain its thriving mining industry. This expansion also unconstitutionally included a corner of Texas. When Congress set the southern border at the 37th parallel, it did so with the same logic that determined Colorado’s northern border – a desire to create a column of states with the same height and width. Simplicity of shape and size were prioritized over geography, and the border setting truncated the Hispano population in the San Luis Valley of New Mexico Territory. This set off animosity at the local level and in Congress.

In May of 1862, the House of Representatives debated dividing New Mexico in order to create Arizona Territory, and New Mexico’s delegates voiced anger over Colorado’s border with New Mexico Territory. John S. Watts, the delegate from New Mexico, recalled how residents of the San Luis Valley were betrayed when Colorado Territory was made “merely for the purpose of beautifying the lines of the new Territory of Colorado.” The following year, New Mexico’s legislature expressed resentment at the loss of territory and memorialized Congress about the boundary with Colorado, which had been left unsurveyed. New Mexico claimed that Colorado had taken advantage of the unsurveyed land and had started exercising their authority much further south than they were entitled to.

In 1865, New Mexico delegate Francisco Perea spoke before the House Committee on the Territories in favor of bringing the San Luis Valley settlements back into New Mexico Territory. He derided the “evenness and symmetry” of Colorado’s southern boundary, stating that the focus on a straight border cut off a fertile part of New Mexico and betrayed the long-standing interests of people who had always belonged to the rest of the New Mexico Hispano culture. His sentiments were echoed by the Santa Fe Weekly Gazette, which wrote that although clean-cut borders were pleasing to the eye, the border setting between New Mexico and Colorado did a disservice to the local population of Hispanos. In the end, Congress refused to change Colorado’s southern border, beyond addressing small surveying inaccuracies.

Surveying ambiguities over the exact location of the border were left unresolved by Congress over the years, despite mounting frustration from New Mexico. In 1925, the US Supreme Court deemed that although a more accurate survey of the border existed, the boundary in force took precedence over a later survey. This confirmed that New Mexico would officially lose thousands of acres to Colorado.

So it is that Colorado stretches from 37 degrees to 41 degrees latitude and 25 degrees to 32 degrees longitude. And you might be surprised to learn that it does not have four sides, but 697 – due to a large amount of small surveying errors. There have been attempts to change Colorado’s borders; as recently as 2013, northeastern Colorado county commissioners encouraged a small movement for the area to become its own state, which would be known as North Colorado or New Colorado. This was mostly a symbolic discussion, as some Colorado counties wanted to make a statement against policies being made at the state level. The boundaries determined by the state constitution in 1876, however, have not changed since Colorado became a state.

Colorado’s borders were influenced by a desire by the US government to create states of equitable size, placing a priority on geometric design instead of working around or with geographic barriers. Colorado’s four borders are consistent with this policy and have given us a uniquely symmetrical shape and size on the nation’s map.

[1] Everett, “Creating the American West,” 14.

[2] To read more about Colorado’s failed attempts at achieving statehood before 1876, please see the following article: https://www.denverpost.com/2006/07/31/civil-rights-role-in-colorado-statehood/

[3] Gower, “Kansas Territory and Its Boundary Question.”

References

Abbott, Carl, Stephen J Leonard, and Thomas J Noel. Colorado: A History of the Centennial State. Fifth. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2013.

American Library Association. “Indigenous Tribes of Colorado.” American Library Association, November 21, 2017. https://www.ala.org/aboutala/offices/denver-colorado-tribes.

“Articles of Confederation (1777).” National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/articles-of-confederation#:~:text=The%20Articles%20of%20Confederation%20were,day%20Constitution%20went%20into%20effect

Berwanger, Eugene H. The Rise of the Centennial State: Colorado Territory, 1861-76. Urbana, Illinois: University Of Illinois Press, 2007.

Cengage. “Jefferson Territory | Encyclopedia.com.” www.encyclopedia.com. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/jefferson-territory.

Everett, Derek R. Creating the American West: Boundaries and Borderlands. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Frederic Logan Paxson. History of the American Frontier, 1763-1893. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Riverside Press, 1924.

Geurts, Jennie. 2014. “How Rivers Shaped the Shape of Colorado.” Water Education Colorado. July 24, 2014. https://www.watereducationcolorado.org/publications-and-radio/blog/how-rivers-shaped-the-shape-of-colorado/.

Gower, Calvin. “Kansas Territory and Its Boundary Question, 1: ‘Big Kansas’ or ‘Little Kansas.’” Www.kshs.org 33, no. 1 (1967): 1–12. https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-quarterly-kansas-territory-and-its-boundary-question/13180.

History, Art & Archives: United States House of Representatives. “Draft Bill for Colorado Territory | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives.” history.house.gov. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://history.house.gov/HouseRecord/Detail/15032436207.

History Colorado. “Carving up a Continent: State Boundaries in the American West, Feat. Dr. Derek Everett.” www.youtube.com, October 5, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EUit0Mj5QH8.

History Colorado, and Michael Troyer. “Colorado Territory | Articles | Colorado Encyclopedia.” Coloradoencyclopedia.org, February 25, 2016. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/colorado-territory.

Humeyumptewa, Aleks, and Tracie Etheredge. “An Inventory of the Records of Arapahoe County, Colorado.” Denver, Colorado: The Colorado Historical Society, 1994. https://www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2018/mss.00015_arapahoe_county_colorado.pdf.

“Is Colorado a Square State?” 2016. Denver Public Library History. August 1, 2016. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/colorado-square-state.

Jacobs, Frank. “Colorado Is Not a Rectangle—It Has 697 Sides.” Atlas Obscura. Big Think, April 14, 2023. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/is-colorado-a-rectangle.

Library Of Congress, and Sponsoring Body Library Of Congress. Center For The Book. How the States Got Their Shapes. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, -07-15, 2008. Video. https://www.loc.gov/item/2021687996/.

Maness, Jack. “When Colorado Was Kansas, and the Nation Was (Even More?) Divided.” Denver Public Library, January 26, 2017. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/when-colorado-was-kansas-and-nation-was-even-more-divided.

Paxson, Frederic. “The Boundaries of Colorado.” The University of Colorado Studies 2, no. 2 (July 1904).

Stein, Mark. How the States Got Their Shapes. New York: Smithsonian Books/Collins, 2008.

The U.S. Today, with Dates of Statehood Wall Map. Mapszu. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0268/2549/0485/products/maps.com-the-u.s.-today-with-dates-of-statehood-wall-map_2400x.jpg?v=1572562951.

Trembath, Brian. “Jefferson Territory: The Renegade State That Almost Replaced Colorado.” Denver Public Library, June 24, 2020. https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/jefferson-territory-renegade-state-almost-replaced-colorado.

www.native-languages.org. “Colorado Indian Tribes and Languages.” Native Languages of the Americas. Accessed June 6, 2023. http://www.native-languages.org/colorado.htm.

Wikipedia. “Colorado Territory,” June 2, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorado_Territory.

Wikipedia. “Four Corners,” May 7, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_Corners#:~:text=The%20Four%20Corners%20area%20is.

Zimmer, Amy. “Jefferson’s Legacy in Colorado.” www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org. Colorado Virtual Library, April 11, 2013. https://www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org/resource-sharing/state-pubs-blog/jeffersons-legacy-in-colorado/.