by Sharon Eubanks

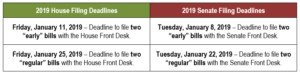

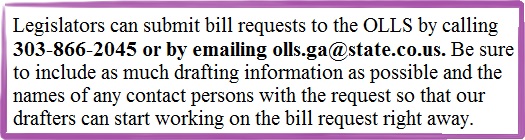

With the 2019 legislative session under way, legislators have already been interacting with the staff of the Office of Legislative Legal Services for their bill and amendment requests. But the Legislative Legal Services staff, comprised of attorneys and other professional staff, provides a variety of written materials and services to legislators in addition to their bill and amendment drafting needs. We encourage legislators to learn more about and make full use of the products and services we can provide. Please visit our web page at https://leg.colorado.gov/agencies/office-of-legislative-legal-services.

Legislative Legal Services is the General Assembly’s nonpartisan legal staff agency. As legislative lawyers, we maintain an attorney-client relationship with the General Assembly, as an institution, and not with each legislator. Therefore, we are obligated to serve the best interests of the institutional client, the General Assembly, as distinguished from the individual interests of any legislator. However, when working individually with legislators, we are statutorily bound to maintain the confidentiality of all bill and amendment requests before introduction, and we are ethically bound to maintain the confidentiality of the communications we have with each legislator, as a constituent of the institution.

In addition to our primary function of drafting bills, resolutions, and amendments, the Legislative Legal Services staff, upon request, can provide legislators with written materials to help them understand Colorado law and what other states are doing to address various issues and to help them explain their bills. Due to time constraints created by bill and amendment drafting demands, which are our first priority during the legislative session, our staff may not always be able to respond immediately to every legislator’s request. But we do our best to provide the requested materials as soon as practicable, time permitting, and on a first-come, first-served basis. Examples of ancillary materials available upon request include:

- More-detailed, written explanations of bills;

- Summaries of changes made to a bill in committee, in the first house, or in the second house;

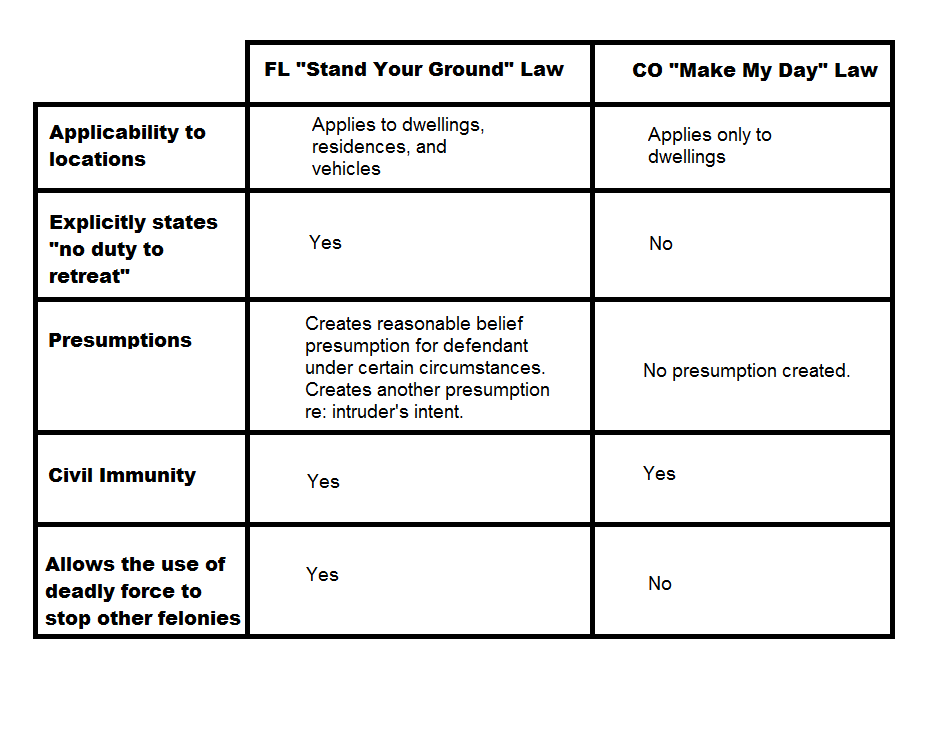

- Tables comparing bill provisions;

- Explanations of state or federal statutes;

- Summaries of case law relevant to a bill;

- Summaries of case law interpreting a particular statute or issue;

- Legislative histories of issues or bills;

- Legislative histories of constitutional or statutory provisions;

- Comparisons of Colorado law with the law of other states on particular issues; and

- Lists of all Colorado statutes addressing an issue.

Our office also provides written legal opinions, including written legal opinions on issues relating to pending legislation. We hold legal opinion requests in strictest confidence. We will not release a written memorandum to other persons without the permission of the legislator who requested it. And we will give the same answer if another legislator asks us the same question, which will result in identical legal opinions for different legislators.

There are some limitations on the materials and services we can provide to legislators due to our role as nonpartisan legislative staff. Examples of the documents and tasks that Legislative Legal Services staff cannot provide include:

- Voting records on an issue or bill;

- Talking points advocating for or opposing a policy position;

- Conveying messages that encourage a legislator to vote for a bill or discourage a legislator from voting for a bill;

- Soliciting legislators as joint prime sponsors, cosponsors, or second house sponsors;

- Violating confidentiality, e.g., telling a legislator about amendments prepared for other legislators to his or her bill, telling a legislator what another legislator said or told others about the legislator’s bill, or telling a legislator what legal advice our office gave another legislator;

- Assisting a legislator in counting votes; and

- Advocating for passage or defeat of legislation on policy or any other grounds.

These lists illustrate the materials or services we can and cannot provide, but they are not exhaustive. If a legislator has a request for materials or assistance, please ask us. If it’s something we can provide, we will do so.

The Legislative Legal Services staff is ready to provide the services and support to help the members of the Seventy-second General Assembly have a productive and successful legislative session in 2019. We encourage legislators to utilize the Legislative Legal Services staff for all their legislative needs, not just for bill and amendment drafting.