by Patti Dahlberg and Jessica Chapman

CDOT – So What Do They Do?

The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) has been around in some form or another since 1910—its inception was roughly parallel to the increasing availability of automobiles in the state. In a previous LegiSource article, we explored the history and transformation of the department over the years and its role in building Colorado’s roadway system. But what is the department doing for Colorado transportation now? Maybe a better question is what isn’t the Colorado Department of Transportation doing?

The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) has been around in some form or another since 1910—its inception was roughly parallel to the increasing availability of automobiles in the state. In a previous LegiSource article, we explored the history and transformation of the department over the years and its role in building Colorado’s roadway system. But what is the department doing for Colorado transportation now? Maybe a better question is what isn’t the Colorado Department of Transportation doing?

Overview

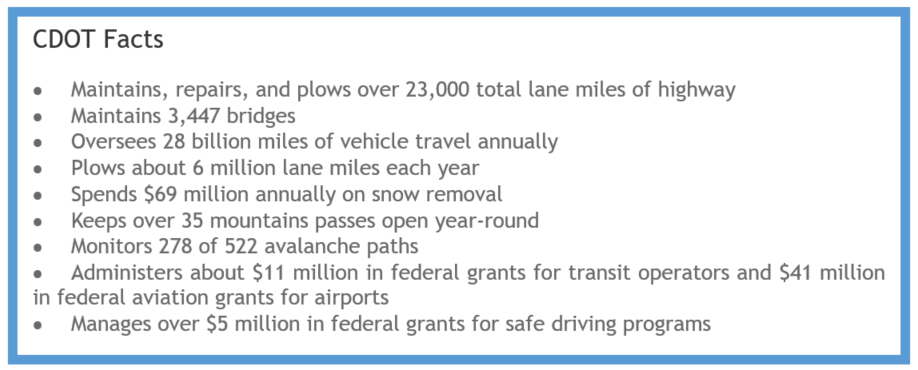

The department’s prime directive is to ensure that Colorado has a safe and efficient  transportation system by building and maintaining state and federal highways (not local and residential roads, which are the responsibility of cities and counties). Of the department’s budget (which totals over $1.7 billion for FY 2024-25), 58% is used just to maintain the current system of roads in the state.

transportation system by building and maintaining state and federal highways (not local and residential roads, which are the responsibility of cities and counties). Of the department’s budget (which totals over $1.7 billion for FY 2024-25), 58% is used just to maintain the current system of roads in the state.

In order to ensure safe, efficient roads, the department provides three main services:

- snow and ice operations;

- roadway maintenance and preservation; and

- construction management.

To enhance public safety, CDOT provides:

- traffic monitoring;

- avalanche control;

- rockfall mitigation;

- mudslide clean-up and mitigation;

- transit development and grants; and

- traffic safety education.

Some Specifics

Emergency Response. One example of CDOT’s valuable service to the state involves its response to the mudslides, caused by heavy rain in July 2021, that closed I-70 through Glenwood Canyon for more than two weeks. CDOT employees were immediately on-site to assess the damage, help trapped motorists, and put in place an emergency plan for clean-up and repair.

response to the mudslides, caused by heavy rain in July 2021, that closed I-70 through Glenwood Canyon for more than two weeks. CDOT employees were immediately on-site to assess the damage, help trapped motorists, and put in place an emergency plan for clean-up and repair.

Multi-year Projects. CDOT also undertakes many multi-year projects at any given time. Currently, the department is working to expand I-25 from Mead to Berthoud. Once this project is completed it will be the first time there will be more than two lanes on I-25 from Denver to Fort Collins in both directions. Other highway projects include the I-70 Floyd Hill project, I-70 mountain corridor project, I-76 York to Dahlia bridge reconstructions, and improvements to U.S. 85 (Santa Fe Drive). In addition, there is always the normal ongoing work of resurfacing streets; replacing traffic signals; constructing retaining walls, curbs, and bridge safety work; installing wildlife fencing; improving on-ramps; and relocating bike trails throughout the state to keep CDOT busy.

Quite simply, CDOT helps Colorado motorists (as well as planes, trains, and buses) get where they need to go in rain, snow, or shine. There are no breaks for the maintenance and response crews—they are called out day and night, weekends, and holidays to highway accidents and road repairs.

Thinking Outside the Box

And if road maintenance and repair isn’t enough, CDOT, in collaboration with the Town of Frisco and the Department of Local Affairs, developed a plan to build single-family homes and apartments in Frisco to provide affordable housing for mountain-based employees. Making mountain housing more accessible will allow CDOT to recruit more employees and keep essential snowplow operators and other road maintenance specialists closer to the areas where they are needed.

CDOT also boasts a Division of Aeronautics, a Division of Transit and Rail, regional bus service and environmental and research services. They even have an Archaeology and History department and a paleontologist on staff! CDOT has been involved with the planning for establishing rail service through northwest Colorado and working with the Front Range Passenger Rail District on providing service along the Front Range, from Pueblo to Fort Collins and eventually to Wyoming and New Mexico. The recent enactment of Senate Bill 24-184 along with the availability of federal transportation money is expected to help fund these projects.

Public Service. CDOT doesn’t just take care of the roads. It also plays an active role in trying to keep travelers informed on road conditions and even provides estimated travel times to help motorists make informed decisions. Their website houses extensive information on its programs, projects, and goals, as well as road and weather conditions (easily accessed through www.cotrip.org or by calling 511). Construction reports are available through the Travel page. For information about safety initiatives, visit the Safety page. You can also get general information about Express Lanes. And they even have their own YouTube channel.

Planning for the Future

Good transportation systems require a solid transportation planning process. Colorado’s transportation planning process includes the development of a Statewide Transportation Plan, Regional Transportation Plans, and a Statewide Transportation Improvement Program. The planning process goes through several levels of planning and routinely invites public involvement.

- Regional Transportation Plans. The department gathers input from 15 planning regionsto develop regional transportation plans for each region. These plans typically establish long-term transportation investment priorities and are consolidated and incorporated in the Statewide Transportation Plan.

- Statewide Transportation Plan. State law requires that the department produce a 20-year plan and update it every few years. The current Statewide Transportation Plan (2045)estimates the state’s needs and revenue for the years 2016 to 2045. The plan outlines funding, anticipated future transportation needs, and strategies to achieve its goals.

- Statewide Transportation Improvement Program. Federal regulations require the state to produce a Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP).This is a 4‑year planning document for state transportation projects which CDOT updates annually. Projects included in the annual plans come from the 20-year statewide transportation plan.

CDOT also takes climate change into account in its planning process. For example, a rule change in 2021 requires transportation projects demonstrate that potential greenhouse gas emissions from the project not exceed certain limits.

There’s no doubt about it, Colorado has a mobile society and transportation impacts its citizens—residents and visitors alike—on a daily basis.

Sources:

- https://www.codot.gov/

- https://www.codot.gov/programs/your-transportation-priorities

- https://leg.colorado.gov/content/department-transportation-cdot

- http://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/14-24_transportation_planning_and_funding_issue_brief.pdf

- https://www.vailmag.com/news-and-profiles/2022/06/eb00812f-aa06-46d9-92c7-a148dc93fdac

- https://www.codot.gov/news/2023/may/groundbreaking-new-granite-park-employee-housing-in-frisco

- https://www.vaildaily.com/news/new-passenger-rail-line-in-the-mountains-gets-on-track-after-colorados-governor-signs-funding-bill/