by Jennifer Gilroy, Michael Dohr, and Jessica Chapman

Editor’s note: This article was originally written by Patti Dahlberg and Jennifer Gilroy and published on December 22, 2016. The article has been edited and updated.

Bill requests are coming in hot here at the OLLS and drafting season is well underway. That means now is probably a good time to review some of the basics of bill sponsorship.

Bill Sponsor Basics

Prime Sponsorship – First House. The legislator who introduces and carries a bill is called the prime sponsor of the bill. Bills cannot be introduced without a prime sponsor. Every bill must have at least one prime sponsor in each chamber (or house) before it can be heard in both chambers. In both the House and the Senate, the prime sponsor (and joint prime sponsor if there is one) is responsible for explaining the bill in committee and in debate on the House or Senate floor. A prime sponsor also typically arranges for witnesses to testify in favor of the bill in committee.

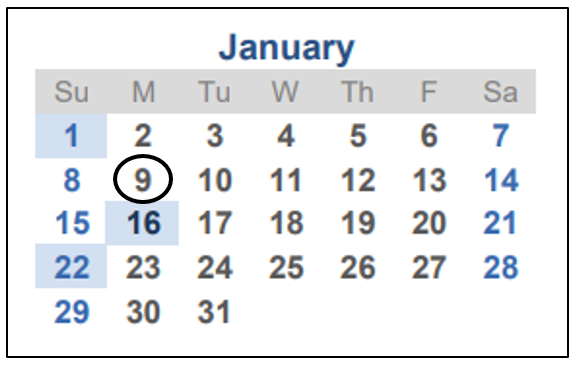

A legislator can be the first house prime or joint prime sponsor for only five bills, unless the legislator has special permission from the committee on delayed bills (leadership) to carry more. But a legislator can agree to be the prime or joint prime sponsor of a bill in the second house on as many bills as the legislator wants.

Prime Sponsorship – Second House. The prime sponsor in the first house (also known as the house of introduction) is responsible for asking a legislator in the second (or opposite) house to carry the bill in that house. The prime sponsor in the first house does not have to identify a second house prime sponsor before the bill is introduced in the first house, but the bill must have a second house prime sponsor before the bill can be heard on third reading in the first house.

Before a bill can move to the second house, the second house prime sponsor must inform the House Chief Clerk or the Secretary of the Senate of that legislator’s intent to serve as the second house prime sponsor. Prime sponsors’ names in both houses are listed on the bill in bold text.

Sponsorship and Co-sponsorship. When legislators want to show support for a bill, but not take on the responsibility of actually carrying the bill, they may sign on as sponsors or co-sponsors of the bill. If a legislator adds the legislator’s name to a bill before it is introduced, the legislator is a sponsor of the bill. If a legislator adds the legislator’s name to a bill after it is introduced, the legislator is referred to as a co-sponsor. Co-sponsors are added immediately following adoption of a bill on third reading.

Joint Prime Sponsorship

Joint Prime Sponsorship. When two legislators in one house want to carry a bill together, we refer to them as joint prime sponsors. A bill that has joint prime sponsors in one house may or may not have joint prime sponsors in the other house. The rules for joint prime sponsorship are similar for the House (House Rule 27A(b)) and the Senate (Senate Rule 24A(b)).

Joint prime sponsorship counts against both legislators’ five-bill limit in the first house. Both joint prime sponsors must verify their desire to be joint prime sponsors. A legislator cannot be added as a joint prime sponsor in the first house if that legislator has already submitted five bill requests, unless that legislator has received permission from leadership. The prime sponsor in the first house must notify the House Chief  Clerk or the Secretary of the Senate, as appropriate, of any changes in bill sponsorship so that the changes are reflected in subsequent versions of the bill.

Clerk or the Secretary of the Senate, as appropriate, of any changes in bill sponsorship so that the changes are reflected in subsequent versions of the bill.

Joint prime sponsorship does not count against the five-bill limit for either legislator in the second house. Again, both joint prime sponsors must verify their desire to be joint prime sponsors.

Joint prime sponsors are typically determined prior to the bill’s introduction. However, in limited circumstances, joint prime sponsors may be added or changed after introduction immediately after second reading but prior to adoption of the bill on third reading. The House and Senate front desk staff can help with this process.

Bill Sponsor FAQs:

How do I add sponsors to my bill before it is introduced?

Before your bill is introduced you can invite other legislators to be sponsors on your bill via the Electronic Sponsorship feature in iLegislate. Electronic Sponsorship operates similarly to an Evite: You may invite legislators to sponsor your bills and you may share draft files with them. Those legislators may choose whether they want to be a sponsor on your bill. If a legislator wants to be a sponsor on your bill but is not able to indicate that through iLegislate and the bill is still in the Office of Legislative Legal Services’ (OLLS) possession, the legislator may simply notify the OLLS in person, by phone, or by email that the legislator would like to be a sponsor on another legislator’s bill. A legislator may not be added to one of your bills as a sponsor without that legislator’s permission and a legislator will not be added to your bill without your permission. Once your bill is delivered by the OLLS to your chamber’s front desk, the OLLS cannot add any more sponsors. (In special circumstances, the House or Senate front desk staff may be able to add sponsors before a bill is printed, but you must contact your chamber’s front desk staff to see if this special circumstance exists.)

The OLLS will deliver your prefile bill (your first bill to be introduced) directly to the House or Senate front desk because that bill must be introduced on the first day of session. The OLLS will deliver your other bills to the front desk or to you, as you direct. Do not contact the OLLS to add sponsors after your bill has been delivered to the front desk or to you. Once a bill is delivered, all sponsor additions or changes must go through House or Senate staff.

How do I add sponsors to my bill after it is delivered for introduction?

If you direct the OLLS drafter to deliver your bill (other than your prefile bill) to you personally and not your chamber’s front desk, the OLLS staff will give the bill to the sergeants who will then deliver it to you. If the bill is delivered to you prior to its introduction deadline you can show it to other legislators and have them sign the sponsor form attached to the bill or go through iLegislate. The bill delivered to you will include a sponsor form stapled to a heavier sheet of green paper (if you’re a Representative) or cream-colored paper (if you’re a Senator). This is called a bill back. Please do not separate the bill from the bill back and sponsor form.

After you give the bill back (and attachments) to the front desk, the front desk staff will review the sponsor form and add the names of those legislators who have signed the form indicating their desire to be sponsors of your bill. These sponsor names will appear on the introduced version of the bill. Sponsors cannot be added to your bill after the front desk has sent it out for printing. After your bill has been introduced, however, other legislators may add their names as co-sponsors following passage of your bill on third reading.

Feel free to contact the OLLS front office, your drafters, or the House and Senate front desks with any questions regarding bill sponsorship. You may contact the OLLS staff to inquire about sponsorship prior to your bill being delivered to the House or Senate for introduction, at (303) 866-2045 or olls.ga@coleg.gov. Once your bill has been delivered for introduction, you may contact the House or Senate front desk staff with your sponsorship questions.