by Patti Dahlberg

As Colorado’s registered voters will be receiving ballots for the November election within the next couple of weeks, this is an appropriate time to start looking at some of the many questions that will be on that ballot. This election is about more than just the presidential election; voters will also decide who fills the normal state and local offices and the fate of 14 statewide ballot measures.

You may want to open your ballot as soon as you receive it and start researching names and issues. Early voting starts on October 21, and all ballots must be turned in by 7 p.m. on November 5.

In the meantime, you’ll find the 14 statewide ballot measures demanding your attention listed below, along with a brief description of each measure. A far better resource for ballot information is, of course, the State Ballot Information Booklet, more commonly referred to as the “Blue Book.” The Blue Book is mailed to each registered-voter household, and that mailing has begun, so voters should start finding the Blue Book in their mailboxes any day now. Additionally, voters can access the electronic Blue Book on the General Assembly’s website.

In the meantime, you’ll find the 14 statewide ballot measures demanding your attention listed below, along with a brief description of each measure. A far better resource for ballot information is, of course, the State Ballot Information Booklet, more commonly referred to as the “Blue Book.” The Blue Book is mailed to each registered-voter household, and that mailing has begun, so voters should start finding the Blue Book in their mailboxes any day now. Additionally, voters can access the electronic Blue Book on the General Assembly’s website.

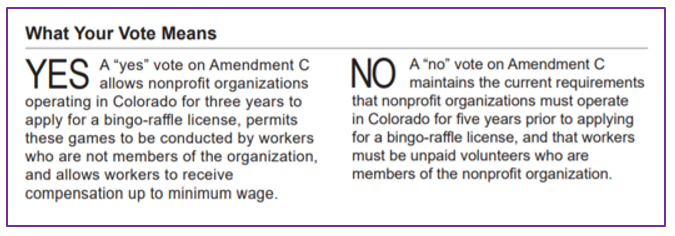

The Blue Book is prepared by Legislative Council Staff and includes an analysis of each ballot measure. Each analysis consists of a summary of the measure, a brief fiscal assessment of the measure’s costs, an explanation of what a “yes” or “no” vote means, how the measure changes the law, major arguments for and against the measure, and sometimes, some background or history of the law behind the measure. In short, the Blue Book hopefully provides enough information to help voters understand each measure’s purpose and effect.

measure. Each analysis consists of a summary of the measure, a brief fiscal assessment of the measure’s costs, an explanation of what a “yes” or “no” vote means, how the measure changes the law, major arguments for and against the measure, and sometimes, some background or history of the law behind the measure. In short, the Blue Book hopefully provides enough information to help voters understand each measure’s purpose and effect.

Amendment G – Modify Property Tax Exemption for Veterans with Disabilities. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to extend the current homestead exemption for veterans with a 100% permanent disability to include veterans who are unable to work a steady job that supports them financially because of a service-connected disability, as determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Amendment H – Judicial Discipline Procedures and Confidentiality. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to create a board consisting of four district court judges, four attorneys, and four citizens that would preside over ethical misconduct hearings involving, and impose sanctions for misconduct by, judges. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Amendment I – Constitutional Bail Exception for First Degree Murder. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to restore the ability of judges to deny bail in first degree murder cases when proof is evident or the presumption is great that the person committed the crime. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Amendment J – Repealing the Definition of Marriage in the Constitution. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to repeal the language defining that only a union of one man and one woman is a valid or recognized marriage in Colorado. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Amendment K – Modify Constitutional Election Deadlines. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to move up by one week the deadline for submitting signatures for initiative and referendum petitions and for judges to file declarations of intent to seek another term. The measure would also require the content of ballot measures to be published in local newspapers 30 days earlier than under current law. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Amendment 79 – Constitutional Right to Abortion. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to make abortion a constitutional right in Colorado and prohibit state and local governments from denying, impeding, or discriminating against exercising that right. The measure would also repeal the existing constitutional ban on state and local government funding for abortion services. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Amendment 80 – Constitutional Right to School Choice. This measure would amend the Colorado Constitution to create the right to school choice for children in kindergarten through twelfth grade and the right for parents to direct the education of their children. The measure would define school choice to include public neighborhood and charter schools, private schools, home schools, open enrollment options, and future innovations in education. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition JJ – Retain Additional Sports Betting Tax Revenue. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to allow the state to keep sports betting tax revenue above the amount previously approved by voters and to use this money for water projects instead of refunding it to casinos and sports betting operators. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition KK – Firearms and Ammunition Excise Tax. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to create a new state tax on firearms sellers equal to 6.5% of their sales of firearms, firearm parts, and ammunition. This new tax revenue would be exempt from the state’s revenue limit as a voter-approved revenue change and would be used to fund crime victim support services, mental health services for veterans and youth, and school safety programs. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition 127 – Prohibit Bobcat, Lynx, and Mountain Lion Hunting. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to prohibit the hunting or trapping of bobcats, lynx, and mountain lions, except under certain circumstances, and establish penalties for violations. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition 128 – Parole Eligibility for Crimes of Violence. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to increase the amount of prison time a person convicted of certain violent crimes must serve before becoming eligible for discretionary parole or for earned time reductions and to make a person convicted of a third violent crime ineligible for discretionary parole or earned time reductions. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition 129 – Establishing Veterinary Professional Associates. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to create a state-regulated profession of “veterinary professional associate” in the field of veterinary care and outline the education and qualifications required for this position. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition 130 – Funding for Law Enforcement. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to direct the state to spend $350 million to help recruit, train, and retain local law enforcement officers and provide additional benefits to families of officers killed in the line of duty. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Proposition 131 – Establishing All-Candidate Primary and Ranked Choice Voting. This measure would amend the Colorado Revised Statutes to create an all-candidate primary election for certain state and federal offices, where the top four candidates would advance to the general election. Additionally, in the general election, voters would be allowed to rank those candidates in order of preference, and the votes would be counted over multiple rounds to determine the winner. (Link to ballot analysis.)

Additional information on Blue Books and the Blue Book process can be found on the General Assembly’s website and in this 2020 LegiSource article. You can also find information on the ballot proposals filed by citizens (initiatives) on the Secretary of State’s Initiative Filings page.