by Julie Pelegrin

Editor’s note: This article was originally posted on March 29, 2018. It has been updated for this posting.

With just a few weeks left in the 2019 legislative session, a legislator’s thoughts turn to…conference committees!

So far this session, the House and the Senate have sent just five bills to conference committee. But there are still more than 300 bills pending in the House and the Senate for this session; chances are good, the number of conference committees will increase. So now seems like a good time for a quick refresher course on the ins and outs of conference committee procedure.

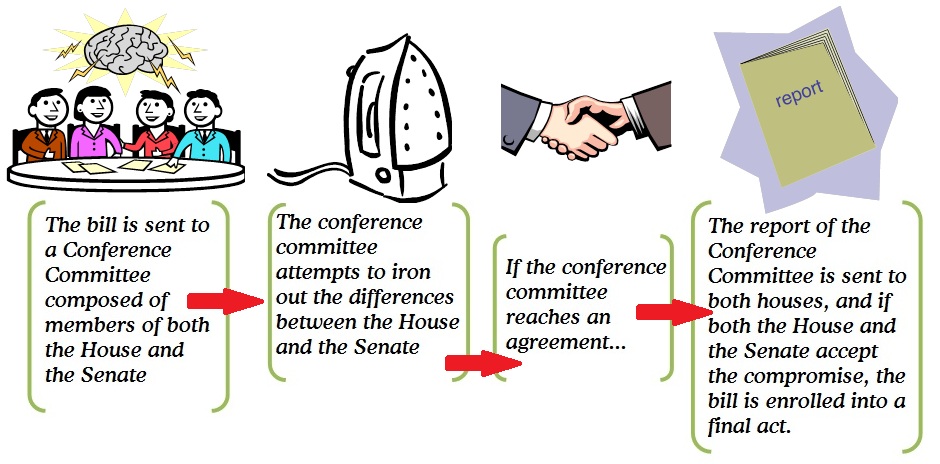

For a bill to go to the Governor, it must pass both the House and the Senate in exactly the same form. If the second house amends a bill, it cannot go to the Governor for signature unless the first house accepts, or “concurs in,” the second house amendments and readopts the bill or unless both houses form a conference committee to create a report that resolves the differences between the two versions.

There is a third option, but it can be risky. A legislator can move for the first house to adhere to its position (i.e., refuse to consider any changes to the bill proposed by the second house). At that point, the second house can choose to recede from its changes and adopt the version of the bill that the first house passed. However, the second house can also choose to adhere to its position (i.e. refuse to consider adopting the first house’s version of the bill). Most often, when the first house adheres to its position and refuses to discuss a compromise, the second house also adheres. If this happens, the bill is dead.

But, let’s assume that the bill sponsor moves to reject the second house amendments and request the formation of a conference committee. The conference committee consists of three persons appointed from each house: Two majority party members and one minority party member. The Speaker and the President will each appoint the two majority members from their respective houses, and the Minority Leaders will each appoint the minority members from their respective houses. In most cases, the bill sponsors in both houses are appointed to the conference committee, and the bill sponsors can submit their preferences for the other members they would like to see appointed to the conference committee from their respective houses.

But, let’s assume that the bill sponsor moves to reject the second house amendments and request the formation of a conference committee. The conference committee consists of three persons appointed from each house: Two majority party members and one minority party member. The Speaker and the President will each appoint the two majority members from their respective houses, and the Minority Leaders will each appoint the minority members from their respective houses. In most cases, the bill sponsors in both houses are appointed to the conference committee, and the bill sponsors can submit their preferences for the other members they would like to see appointed to the conference committee from their respective houses.

The conference committee’s report can address any of the differences between the two versions of the bill. But, if the conference committee wants to address language that was not changed by the second house or address an issue that fits within the bill title, but was not included in either version of the bill, the bill sponsors must ask their respective chambers for permission “to go beyond the scope of the differences” between the two versions. Sometimes, the bill sponsors will ask for this permission at the same time that they request a conference committee; more often they do not. The conference committee members can discuss changes that are outside the scope of the differences before they ask for this permission, but the members cannot sign the committee report until both houses have granted the committee permission to go beyond the scope of the differences.

The date, time, and location for all conference committee meetings are printed in the House and Senate calendars. After agreeing on wording changes to resolve the differences, the committee may adopt the committee report conceptually or, if the bill drafter prepared the report in advance of the meeting, may adopt the committee report as written. For the report to pass, a majority of the conference committee members from each house (i.e. two House members and two Senate members) must approve the report. Following adoption of the report, the committee members who voted to approve the report sign it. A committee member who voted against the report and any committee member who missed the meeting may also choose to sign the report.

Once the report is signed and turned in to the front desk of the House and the Senate, the house that agreed to go to conference committee, usually the second house, acts first on the report. Usually, the second house adopts the report and readopts the bill as amended by the conference committee report. Then the first house also adopts the report and readopts the bill. At that point, the bill is enrolled and sent to the Governor.

However, either house may choose to adhere to its position, recede from its position, or reject the conference committee report and ask that a second conference committee be formed. Assuming both houses agree to a second conference committee, they will appoint the members of the second conference committee, which may be the same as the first conference committee, and the committee will meet again and attempt to come to another agreement. Only two conference committees can be appointed for a bill. If either house rejects the committee report of the second conference committee, one of the houses will have to recede and adopt the other house’s version, or the bill is dead.

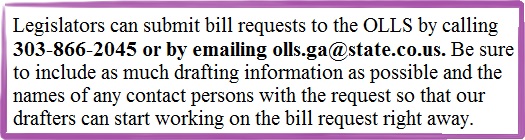

This article describes how conference committees usually work. The OLLS has prepared charts for the House and Senate that explain the possible actions, in addition to adopting a conference committee report, that each house may take in resolving differences between the houses. If you are interested in reading the legislative rules on conference committees, you can find them at House Rule 36, Senate Rule 19, and Joint Rules 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8.