by Julie Pelegrin

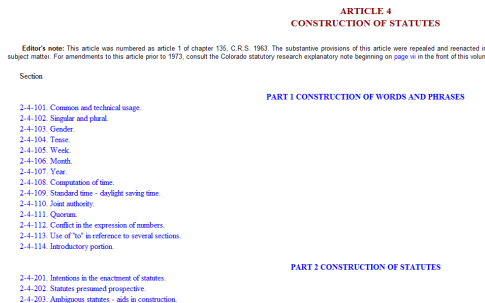

Editor’s Note: This week’s article is the seventh in our series on statutory construction. For previous installments, click on “statutory interpretation” in the tag cloud.

In addition to presumptions and tools for discerning legislative intent, the statutes on construction of statutes provide specific guidance for when a court can salvage part of an otherwise unconstitutional statute and how a court should decide which statute to apply when two statutes conflict.

Statutory Salvage Operations: Severability

Suppose a court interprets a statute and finds that part of that statute is unconstitutional. Does that mean the entire statute is unconstitutional, or can some portions of the statute survive?

The answer turns on the concept of severability. Section 2-4-204, C.R.S., says that, if a court finds part of a statute to be unconstitutional, the remaining constitutional parts of the statute are valid, unless the court finds that those remaining parts are:

- So essential to the unconstitutional part, that the General Assembly would not have passed the constitutional part without the unconstitutional part; or

- So incomplete that they cannot be implemented without the unconstitutional portion.

To illustrate, let’s consider a hypothetical situation: Assume there’s a statute that regulates caterpillar breeders. Under this statute, a caterpillar breeder cannot have more than 1,000 caterpillars at a time and the caterpillar breeder cannot advertise her caterpillar breeding business. A caterpillar breeder sues the state claiming that the statute is unconstitutional because limiting the number of caterpillars and prohibiting advertising restricts her freedom of commercial speech. The court agrees that the prohibition on advertising is unconstitutional and cannot be enforced. However, the court finds that the limit on the number of caterpillars has nothing to do with commercial speech and is constitutional. The court will find that the statute is severable because the limit on the number of caterpillars is not directly related to the prohibition on advertising and can be implemented even though the prohibition on advertising is not enforced.

When Statutes Collide Part I: Specific Controls Over the General…Usually

Sometimes a statute will state a general requirement that is intended to apply in a variety of situations. But another statute may impose a different requirement in a specific situation. How is a court supposed to apply both of these statutes?

Section 2-4-205, C.R.S., directs a court to read the statutes together and give effect to both of them if possible. If the two requirements conflict and they cannot both apply, the court must apply the specific requirement instead of the general requirement. But, if the General Assembly passed the general requirement after it passed the specific requirement and made it clear that the general requirement was intended to replace the specific one, then the court will apply the general requirement, not the specific requirement.

Anot her illustrative hypothetical: Assume there’s a statute that says applications for a professional license must be filed in triplicate with the appropriate licensing agency. But, the statute for licensing professional caterpillar breeders says a caterpillar breeder may submit a single copy of the license application with the professional caterpillar breeders board. Obviously, a court could not apply both of these statutes; one must prevail. The court would allow the caterpillar breeder to file a single copy of the license application with the board, unless the statute that requires the application in triplicate was passed after the caterpillar breeders’ statute, and the bill for the general licensing statute included a statement of legislative intent that it is imperative to good government that all licensing applications be filed in triplicate.

her illustrative hypothetical: Assume there’s a statute that says applications for a professional license must be filed in triplicate with the appropriate licensing agency. But, the statute for licensing professional caterpillar breeders says a caterpillar breeder may submit a single copy of the license application with the professional caterpillar breeders board. Obviously, a court could not apply both of these statutes; one must prevail. The court would allow the caterpillar breeder to file a single copy of the license application with the board, unless the statute that requires the application in triplicate was passed after the caterpillar breeders’ statute, and the bill for the general licensing statute included a statement of legislative intent that it is imperative to good government that all licensing applications be filed in triplicate.

When Statutes Collide Part II: Later In Time Controls

Sometimes two statutes conflict, not because one is general and the other is specific, but because one prohibits what the other allows or requires. As in other cases, the court will first try to reconcile the differences and give effect to both sections. But, under section 2-4-206, C.R.S., if the differences are irreconcilable – there is a true conflict – the statute that has the latest effective date is the one the court will apply. If both statutes were passed in the same legislative session with the same effective date, the statute that has the latest date of passage will apply.

Again, to illustrate: A caterpillar breeder loses his license because he does not post his license in the front window of the breeding building, as required by House Bill 1705. But, the caterpillar breeder argues to the court that he should keep his license because, under Senate Bill 923, a person who posts anything in the window of an insect breeding facility commits the crime of insect cruelty (papers in the window block the sunlight). The court cannot reconcile the conflict between the two statutes, so it looks to the effective dates of the bills. House Bill 1705 had an effective date clause that said it took effect July 1, 2009. Senate Bill 923 passed in 2009 without an effective date clause and without a safety clause – so it took effect August 5, 2009. Senate Bill 923 took effect last, so it controls. The caterpillar breeder does not have to post his license.

If House Bill 1705 and Senate Bill 923 had both passed without a safety clause and without an effective date clause, they would have both taken effect on August 5, 2009. In that case, the court would look for the date on which the Governor signed each of the bills. If the Governor signed House Bill 1705 on May 3, 2009, and signed Senate Bill 923 on May 4, 2009, the court would apply Senate Bill 923.