By Bethanie Pack

Each bill faces a long, arduous journey from introduction to the Governor’s desk, a journey that many bills do not complete. But for those that do, this week’s article maps the process and provides some behind the scenes info on how the work gets done.

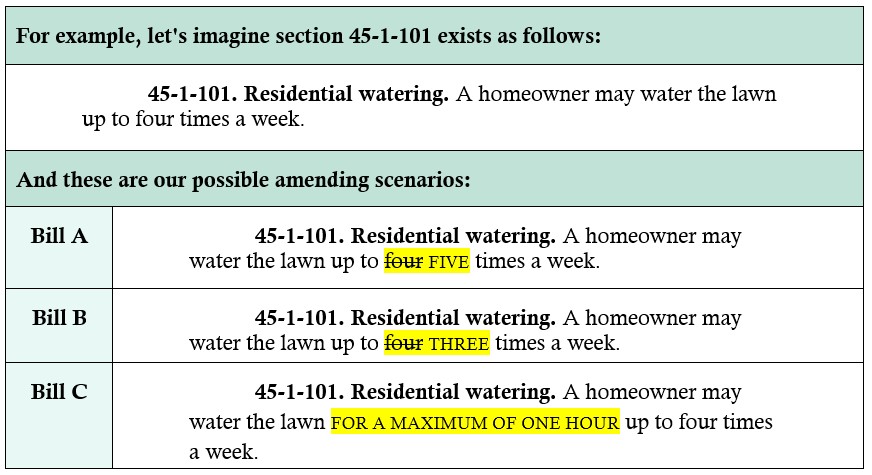

Amending Stages of a Bill

Committee Reports

In the first house, a bill is introduced by reading the title and bill number (the first of three readings) and is then assigned to committee. Bills are often amended in committee, sometimes with multiple amendments. The Legislative Council staff merges the adopted amendments into a committee report for each bill. These committee reports are read across the House or Senate desk (within three legislative days after the hearing) and then published on the General Assembly’s website. At this point, the Enrolling Room —staff of the House or the Senate whose job it is to enroll each bill by inputting the amendments— merges those amendments into the introduced bill, creating an unofficial preamended version of the bill, which shows what the bill will look like if the committee report is adopted on second reading. If the bill is sent to multiple committees, there will be an unofficial preamended version of the bill after each committee report is read across the desk, which will include all the amendments adopted in each committee to date. Unofficial preamended versions of each bill are available on the General Assembly’s website. Click here for more information on committees of reference.

Second Reading

On second reading, the first house Committee of the Whole typically adopts the committee report(s) and sometimes passes additional amendments. Once the first house adopts the Committee of the Whole report, the Enrolling Room merges all of those amendments into the bill, creating the Engrossed version of the bill. Sometimes the Committee of the Whole lasts for many hours and late into the night, and nothing that the Committee of the Whole does is final until the first house adopts the Committee of the Whole report. For example, if Bill A is amended and passed by the Committee of the Whole at 10 a.m. but the Committee of the Whole continues working and is still debating Bill Z at 10 p.m., the amendments to Bill A are not yet adopted and the Enrolling Room cannot create the Engrossed version. The Engrossed versions of the bills are only available after all the bills on the second reading calendar have been addressed, the Committee of the Whole concludes their work, and the first house—sitting as the House or the Senate—adopts the Committee of the Whole report. Click here for more information on the Committee of the Whole.

Third Reading

Generally, third reading amendments are only technical clean-up amendments. If the first house does adopt an amendment on third reading, it can be enrolled into the bill immediately after the bill is passed, creating the Reengrossed version. These amendments are a top priority for the Enrolling Room so that the bill can be transmitted to the second house as soon as possible. Click here for more information on third reading.

This process is then repeated in the second house. The only difference is that the bill is called Revised after second reading in the second house and Rerevised after third reading.

Behind the Scenes

After a bill is amended on the House or Senate floor, staff presses a couple of buttons and then sends the bill off to the printer, right?

Actually, no. At least four sets of eyes proofread and check the amendments before the amended bill goes to the printer. This process could take minutes or hours depending on the complexity, length, and number of amendments that were passed that day.

The House and Senate Enrolling Rooms merge the amendments into the bills, and then there is a meticulous proofing process between the Enrolling Rooms and the Publications Team in the Office of Legislative Legal Services before sending the bills to the printer.

Overview of the Process

The role of the Enrolling Rooms is to verify that all of the amendments are placed into the bill in the correct place. Next, the Publications Team reviews the amendments in the bill for formatting and publications issues. They are looking for things such as numbering discrepancies, coding errors, punctuation errors, and effective date problems. Then, the amendments are given further review by the drafter whose role is to check the amendments within the context of the bill for any legal or substantive issues. This is important because amendments are confidential until moved and often multiple amendments from different legislators are adopted. The drafter needs to make sure the bill remains cohesive with the added amendments.

Why so many steps?

It would be lovely if there was a magical button or fairy dust that placed 105 amending instructions into a 40-page bill, but instead, the process is done manually to catch publishing issues and legal issues that a computer wouldn’t catch. Basically, the process is set up to ensure the best work product possible for the General Assembly, and that means lots of eyes on the bills throughout every step of the process, from the first draft to the Governor’s signature.

Did you know?

- Once the Enrolling Room and Publications Team “approve” the bill with the amendments merged in, it goes public online right away.

- You can look at the bill with the committee amendments before the committee report is adopted on second reading. It’s called a preamended version. It’s an unofficial version, but it’s a helpful tool.

- It’s available after the committee report is read across the desk and the process discussed above is completed.

- You can find unofficial preamended versions on the General Assembly’s website when you search for the bill, scroll down to the “Bill Text” section, and then toggle the “Preamended Versions” dropdown menu.