by Alana Rosen and Nate Carr

If you have ever tasted a Gin Rickey, a Sidecar, or an Old Fashioned, then you have sampled a popular cocktail created during the Prohibition Era. The Prohibition Era, which lasted as a federal ban from January 17, 1920, until December 5, 1933, is remembered for the underworld nightlife of jazz clubs, flappers, and bootleggers and is now, over 100 years later, often romanticized.[1] Recently, the glamorization of the Prohibition Era has even inspired a resurgence of speakeasies, Roaring ’20s costume parties, and the modern-day film interpretation The Great Gatsby with heartthrob Leonardo DiCaprio. Despite the fascination with this era, Prohibition was propelled by more sober reasoning.

The Temperance Movement was a driving political force to pass prohibition legislation. In Colorado and across the country, the Temperance Movement included a number of diverse organizations, such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, religious leaders, itinerant preachers, suffragists, and progressive-minded community members. Temperance reformers believed alcohol was the cause of social problems, and with its eradication, “America would be fully cleansed of sin”.[2] In Colorado, women gained the right to vote in statewide elections in 1893, and many women advocated to ban alcohol because of the link between drinking and domestic violence at home. As early as 1907, temperance reformers in Colorado celebrated the passage of anti-saloon legislation.

in statewide elections in 1893, and many women advocated to ban alcohol because of the link between drinking and domestic violence at home. As early as 1907, temperance reformers in Colorado celebrated the passage of anti-saloon legislation.

In 1907, the Colorado General Assembly passed the first bone-dry law, an act allowing political territories to vote to outlaw the sale of alcohol within the territory.[3] By 1910, 20 out of 25 counties that voted on the question of whether to become anti-saloon territories, chose to become anti-saloon territories. Denver was among the five holdouts. Despite fervent efforts, temperance reformers were unsuccessful in convincing the electorate to add a prohibition amendment to the Colorado Constitution. But that all changed in 1914.

In 1914, Colorado voters passed a constitutional amendment limiting alcohol in the state except for medicinal or sacramental reasons by a vote of 129,589 to 118,017.[4] The constitutional amendment, Article XXII, took effect on January 1, 1916. Under Article XXII, no person, association, or corporation could manufacture for sale or gift, or keep for sale or gift, any intoxicating liquor, except in limited situations.[5]

The City and County of Denver, however, disagreed with Article XXII and continued to issue licenses to businesses to sell intoxicating liquors under its home-rule authority found in Article XX of the Colorado constitution. This disagreement resulted in the Colorado Supreme Court case, People ex rel. Carlson v. City Council of Denver.[6] The Court held that Denver was not exempt from the Article XXII, and the city was required to cancel issued liquor licenses.

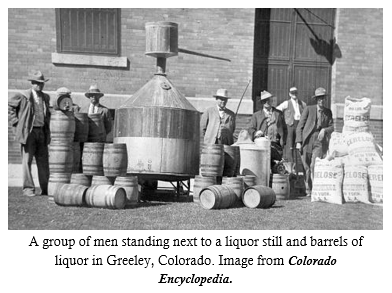

In 1915, the Colorado General Assembly went a step further and passed Senate Bill 80 (S.B. 80), which enacted laws against the possession, distribution, and advertising of intoxicating liquors. S.B. 80 also outlined law enforcement’s duty to search, seize, and destroy intoxicating liquors. If an officer had personal knowledge or reasonable information that intoxicating liquors were kept in any place, the officer could search a business with or without a warrant. The law, however, exempted private residences from these searches. It was reported that on the last night of legal alcohol, December 31, 1915, the New Year’s Eve passed quietly, more like a wake than a celebration to ring in a new year.

In 1915, the Colorado General Assembly went a step further and passed Senate Bill 80 (S.B. 80), which enacted laws against the possession, distribution, and advertising of intoxicating liquors. S.B. 80 also outlined law enforcement’s duty to search, seize, and destroy intoxicating liquors. If an officer had personal knowledge or reasonable information that intoxicating liquors were kept in any place, the officer could search a business with or without a warrant. The law, however, exempted private residences from these searches. It was reported that on the last night of legal alcohol, December 31, 1915, the New Year’s Eve passed quietly, more like a wake than a celebration to ring in a new year.

Later, in 1917, the Colorado General Assembly passed House Bill 164 (H.B. 164), which further limited the importation of intoxicating liquors, reduced the amount of alcohol each household could possess, and created a permit system that made enforcement of the law more efficient.[7] Under H.B. 164, it was unlawful for any person to receive at any one time more than two quarts of intoxicating liquor other than wine or beer, except in circumstances when the intoxicating liquor was consumed for medicinal or sacramental purposes, six quarts of wine, or 24 quarts of beer.

Finally, on November 5, 1918, the Colorado General Assembly adopted an all-encompassing prohibition on intoxicating liquors.[8] The new law strictly limited possession of intoxicating liquors to druggists and broadened the search and seizure powers of law enforcement, including the ability to seize any device used to carry liquor, including automobiles.

Meanwhile, despite the goal to reduce public drunkenness, arrests for drunken disorderly conduct increased during this period. Local crime organizations brewed, transported, and distributed intoxicating liquors. Parents even made bootleg liquor at home to ensure their children would not be poisoned by bad liquor made by underground organizations, though improperly brewed homemade distillations could contain highly toxic methanol or traces of lead from the still. Ingesting such impurities could lead to abdominal pain, anemia, renal failure, hypertension, blindness, and death.

Although Coloradans were imbibing intoxicating liquor behind closed doors, Colorado’s bone-dry laws did not repeal until December 1933. The repeal followed approval of the 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution, which repealed the 18th Amendment, the constitutional provision that prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors. There was a final push by temperance reformers to maintain the bone-dry laws, but in 1933 Colorado voters passed Amendment Seven, finally repealing Prohibition in Colorado.

constitutional provision that prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors. There was a final push by temperance reformers to maintain the bone-dry laws, but in 1933 Colorado voters passed Amendment Seven, finally repealing Prohibition in Colorado.

[1] The 18th Amendment to the Constitution prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors…” The states ratified the 18th Amendment on January 16, 1919. On October 28, 1919, Congress passed the Volstead Act, which provided for the enforcement of the 18th Amendment. Prohibition ended on December 5, 1933, with the ratification of the 21st Amendment.

[2] PBS, Roots of Prohibition, https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/roots-of-prohibition/ (accessed November 2, 2021).

[3] 1907 Colo. Sess. Laws 495.

[4] Dick Kreck, High, Dry Times as Prohibition Era Sobered Denver, Denver Post (July 3, 2009).

[5] Colo. Const. of 1915, art. XXII, § 1.

[6] People ex rel. Carlson v. City Council of Denver, et al, 60 Colo. 370, 153 P. 690 (Colo. 1915).

[7] 1917 Colo. Sess. Laws 280.

[8] 1919 Colo. Sess. Laws 461.