by Patti Dahlberg

The “Red Summer” of 1919 refers to violent race riots that took place in more than 30 cities throughout the country between May and October. The most well-known confrontations were in Chicago, Washington, D.C., and outside of Elaine, Arkansas. The riots in the North marked the culmination of steadily growing tensions surrounding the migration of an estimated half million African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North to work in the factories, warehouses, and mills experiencing severe labor shortages due to military enlistments. When thousands of soldiers returned home from the war, they found few available jobs. Growing financial insecurity caused racial and ethnic prejudices to rage to the surface. At the same time, African-American veterans who had fought and sacrificed for freedom and democracy overseas in WWI found themselves back home and denied basic rights such as adequate housing and equality under the law.

The “Red Summer” of 1919 refers to violent race riots that took place in more than 30 cities throughout the country between May and October. The most well-known confrontations were in Chicago, Washington, D.C., and outside of Elaine, Arkansas. The riots in the North marked the culmination of steadily growing tensions surrounding the migration of an estimated half million African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North to work in the factories, warehouses, and mills experiencing severe labor shortages due to military enlistments. When thousands of soldiers returned home from the war, they found few available jobs. Growing financial insecurity caused racial and ethnic prejudices to rage to the surface. At the same time, African-American veterans who had fought and sacrificed for freedom and democracy overseas in WWI found themselves back home and denied basic rights such as adequate housing and equality under the law.

The first acts of violence occurred in the South and then became more prevalent in northern cities. On July 19, 1919, in Washington, D.C., a group of white men started randomly beating African-American pedestrians and streetcar riders after hearing that an African-American man had been accused of rape. When the police refused to intervene, African-Americans fought back. After four days of rioting, six were dead and another 50 were seriously injured.

On July 27, an African-American teenager drowned in Lake Michigan after being stoned by a group of white youths for violating the unofficial segregation of Chicago’s beaches. His death, and the  police’s refusal to arrest the white man whom eyewitnesses identified as causing it, sparked a week of rioting between gangs of African Americans and white Chicagoans. When the riots finally ended on August 3, 38 were dead and more than 500 injured. In addition, a thousand African-American families lost their homes to vandalism and fire.

police’s refusal to arrest the white man whom eyewitnesses identified as causing it, sparked a week of rioting between gangs of African Americans and white Chicagoans. When the riots finally ended on August 3, 38 were dead and more than 500 injured. In addition, a thousand African-American families lost their homes to vandalism and fire.

On September 30 outside of Elaine, Arkansas, in a confrontation between white planters opposing the union organization efforts of African-American sharecroppers, a white man was killed. Rumors of an African-American revolt caused whites to gather en masse to “put down” what was being called a “black insurrection.” Men from other counties joined in and soon 500 to 1,000 armed men in mobs were attacking African Americans on sight. There was no exact account of the number of casualties but estimates put the number killed somewhere between 200 and 800. Colorado did not evidently experience the level of race violence that occurred in other states.

Anarchists and the Red Scare

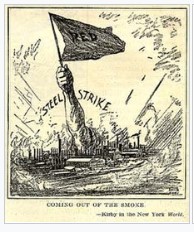

In April of 1919, more than 30 bombs were mailed to prominent citizens, including John D. Rockefeller, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, and America’s first Secretary of Labor, William Wilson. Most of the bombs did not detonate or were discovered in New York post offices before being delivered, so there was no loss of life although there was one reported serious injury. No one was prosecuted for the mail bombs, but history presumes that those responsible were anarchists, specifically followers of Italian anarchist Luigi  Galleani. It was widely believed that “Galleanists” orchestrated the mail bombs and were also responsible for a coordinated attack on judges, politicians, law enforcement officials, and prominent businessmen in eight American cities on June 2. Large bombs, each fueled by 20 pounds of dynamite, exploded at residences in Boston, Cleveland, New York City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. The blasts shook neighborhoods and destroyed homes. Debris and shrapnel injured several people. A night watchman in New York was killed and when the bomb at U.S. Attorney General Palmer’s residence in D.C. exploded prematurely, it killed the anarchist carrying it and narrowly missed a young Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt who had passed by the house just moments before. None of the targeted individuals were killed. Bomb scares continued throughout the year and into 1920, when a large explosion in front of the Morgan Bank at 23 Wall Street killed more than 30 people and wounded hundreds more. To deflect the impending threat of anarchy and violence, Colorado legislators passed Senate Bill No. 30 “Red Flag – Display made a Felony” to prevent the display of the red flag, considered to be “the emblem of anarchy,” in public in the State of Colorado.

Galleani. It was widely believed that “Galleanists” orchestrated the mail bombs and were also responsible for a coordinated attack on judges, politicians, law enforcement officials, and prominent businessmen in eight American cities on June 2. Large bombs, each fueled by 20 pounds of dynamite, exploded at residences in Boston, Cleveland, New York City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. The blasts shook neighborhoods and destroyed homes. Debris and shrapnel injured several people. A night watchman in New York was killed and when the bomb at U.S. Attorney General Palmer’s residence in D.C. exploded prematurely, it killed the anarchist carrying it and narrowly missed a young Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt who had passed by the house just moments before. None of the targeted individuals were killed. Bomb scares continued throughout the year and into 1920, when a large explosion in front of the Morgan Bank at 23 Wall Street killed more than 30 people and wounded hundreds more. To deflect the impending threat of anarchy and violence, Colorado legislators passed Senate Bill No. 30 “Red Flag – Display made a Felony” to prevent the display of the red flag, considered to be “the emblem of anarchy,” in public in the State of Colorado.

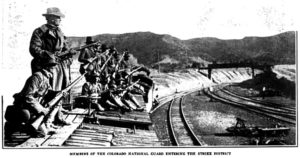

The air was heavy with the fear of the next “red terror” attack. U.S. Attorney General Palmer responded with a massive investigation by the decade-old Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) led by a young Justice Department attorney named J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover and his team collected detailed information on suspected radicals and their activities. Attorney General Palmer used this information to initiate a series of raids, called “Palmer Raids,” to target radical organizations throughout the country. Not to be outdone, Governor Oliver H. Shoup called Colorado legislators into a Special Session to “curb and eradicate threats against our form of government.” The Colorado legislature passed House Bill No. 1 “Anarchy and Sedition – Suppression of Conspiracies against State” describing what constituted the felony of anarchy and sedition in Colorado and assigning a penalty of up to 20 years of prison time. The legislature also appropriated funds to pay for any expenses incurred in “suppressing threatened tumult and riot in the state, and in maintaining law and order therein by the use of the National Guard.”

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) led by a young Justice Department attorney named J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover and his team collected detailed information on suspected radicals and their activities. Attorney General Palmer used this information to initiate a series of raids, called “Palmer Raids,” to target radical organizations throughout the country. Not to be outdone, Governor Oliver H. Shoup called Colorado legislators into a Special Session to “curb and eradicate threats against our form of government.” The Colorado legislature passed House Bill No. 1 “Anarchy and Sedition – Suppression of Conspiracies against State” describing what constituted the felony of anarchy and sedition in Colorado and assigning a penalty of up to 20 years of prison time. The legislature also appropriated funds to pay for any expenses incurred in “suppressing threatened tumult and riot in the state, and in maintaining law and order therein by the use of the National Guard.”

During the Palmer Raids, approximately 10,000 people were arrested for allegedly violating the Espionage Act of 1917, the Sedition Act of 1918, or the Immigration Act of 1918. Of those arrested, 3,500 were detained and 556 were eventually deported. After the coordinated raids in 33 cities on January 2, 1920, reports of brutality and detainee abuse became public. The constitutionality of the raids and law enforcement actions during the raids were openly questioned and publicly criticized. Growing distress regarding the abuse of the civil liberties of those arrested simply because they were immigrants turned public opinion against Palmer and his raids. During the January 2nd federal raid in Denver, federal agents could find only eight radicals. After January 1920, the raids tapered off and the country’s fear of insurrection subsided.

During the Palmer Raids, approximately 10,000 people were arrested for allegedly violating the Espionage Act of 1917, the Sedition Act of 1918, or the Immigration Act of 1918. Of those arrested, 3,500 were detained and 556 were eventually deported. After the coordinated raids in 33 cities on January 2, 1920, reports of brutality and detainee abuse became public. The constitutionality of the raids and law enforcement actions during the raids were openly questioned and publicly criticized. Growing distress regarding the abuse of the civil liberties of those arrested simply because they were immigrants turned public opinion against Palmer and his raids. During the January 2nd federal raid in Denver, federal agents could find only eight radicals. After January 1920, the raids tapered off and the country’s fear of insurrection subsided.

Sources:

http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=1102

https://www.fbi.gov/history/brief-history

https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/early-fbi-terrorism-case-062819