by Bethanie Pack

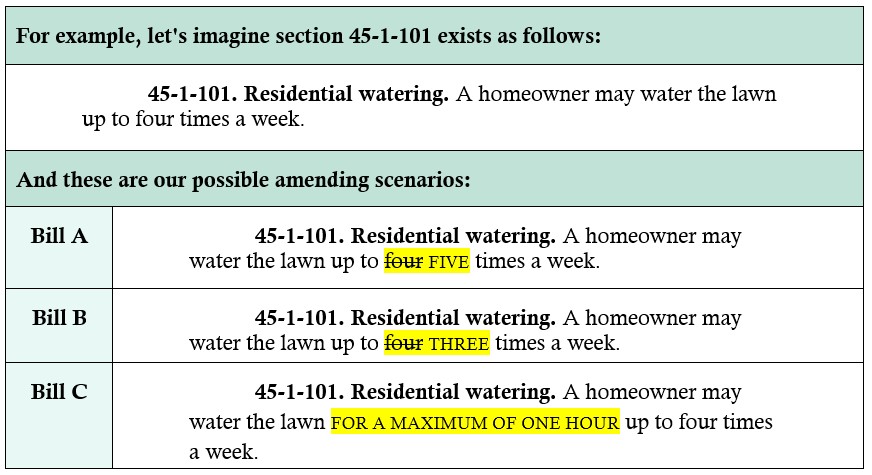

It’s very common for multiple bills to amend the same provision of law in a given session, because let’s face it, great minds think alike, and there are a lot of great minds in our state legislature. So, when this occurs, one of five things can happen:

- The bills are harmonized upon publishing;

- Provisions are renumbered;

- The bills are amended without need of a conflict letter from the Revisor of Statutes;

- The Revisor of Statutes issues a conflict letter to the bill sponsors of both bills notifying them of the conflict and how to address it; or

- As a last resort, one of the bills supersedes the other.

So what in the world does all this mean? Let me explain.

After a bill passes second reading in each house, the publications team (a team in the Office of Legislative Legal Services that works under the direction and supervision of the Revisor of Statutes) performs a database search against all other bills in the current legislative session to ensure no bills change the same provision of law in a conflicting manner.

Harmonize

If only Bill A and Bill C are adopted, then the publications team can harmonize the section upon publication, and there is no conflict. In other words, the two bills “play nice together.” The section would appear as:

45-1-101. Residential watering. A homeowner may water the lawn for a maximum of one hour up to five times a week.

The changes from both bills can be combined in this section and they can be harmonized.

Renumber/Reletter

Now, ignore Bills A, B, and C for a moment, and take as an example two bills that both add a subsection (2) to the current version of 45-1-101. If both bills pass, one of them will be renumbered to add a subsection (3).

Conflict Letter

Back to our original example. If both Bill A and Bill B were to pass, they cannot be harmonized; there is a conflict. The section of law cannot state that a homeowner may water the lawn both three and five times a week. In this scenario, the Revisor of Statutes writes a conflict letter, as directed by Joint Rule 16, to give notice of conflicting provisions to the prime sponsors of the conflicting bills.

These letters are paper copies delivered to the desks of the prime sponsors upon transmittal to the opposite house after third reading. A copy of the letter is also stapled to the billback. The letter contains a statement about the conflict and a statement that the bill drafters know about the conflict and can provide guidance on how to address the issue.

The publications team runs the conflict check after second reading in each house, which sometimes gives the drafter enough time to confer with the prime sponsor and draft a third reading amendment to fix the conflict. This would eliminate the need for a conflict letter before the bill gets transmitted to the opposite house.

Typical resolutions to conflicts by amendment include mirroring the language in both bills to make them harmonizable, making the conflicting provision in one bill contingent on the passage of the other bill so that both provisions don’t go into effect, or eliminating the conflicting provision or moving it to a different place in statute. But sometimes, none of these approaches will work because the bill sponsors don’t agree to the amendments that would harmonize the bills or because harmonizing the bills would defeat the purposes of the bills. In these situations, the legislators may decide to allow one bill to supersede the other.

Supersede

The goal of the publications team is to give effect to every bill. So, allowing one provision of law to supersede another is the last resort and done if an amendment to fix the issue was not adopted. If two bills pass that cannot be harmonized, renumbered, or relettered, and they were not amended to “play nice together,” then one bill will supersede the other where the conflicting provision occurs. Which provision takes effect is typically based on the effective dates of the bills—the amendment with the later effective date prevails. Occasionally two conflicting bills will have the same effective date, in which case the provision that prevails is the one in the bill the Governor signs last. In some cases, however, the bill with the earlier effective date will prevail because it repeals the provision. A bill that repeals a provision will supersede a bill that amends the same provision, even if the amending bill has a later effective date, because the repealed provision is gone by the time the amending provision takes effect, and it cannot be brought back to life to implement the amendment.

For more information on effective dates, see “When Does an Act become a Law? It depends.”