Editor’s note: This article was originally written by Julie Pelegrin and posted on June 28, 2012. This version has been edited and updated for this publication.

If you’re a legislator starting work on legislation for the next session or you just have some questions and are interested in information on specific policy areas, there are several resources available to you.

First, the Office of Legislative Legal Services is available year-round to research any constitutional, statutory, or other legal questions that legislators may have. Whether the question is specific to legislation or whether you are building subject-matter knowledge, we are available to speak with legislators, research issues, meet to discuss legal questions, and provide written materials to assist you in your legislative duties. If a legislator’s questions are more policy related or if you’re interested in learning how state agencies are implementing legislation, the Office of Legislative Legal Services will work with colleagues in the Legislative Council Staff office to provide the answers.

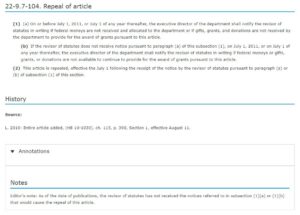

Both offices also have a virtual library of memos and briefs on many legal and policy topics. The Legal Services website has a Resources and Guides page with a cornucopia of resources, including constitutional requirements, bill anatomy, rules of statutory construction, bill requests, legislative lingo, legislative process, house rules at a glance, senate rules at a glance, and many pages covering frequently asked questions. The website also includes summaries of recent judicial opinions and the most recent Digest of Bills, as well as archived digests going back to 1943. The Digest of Bills provides a short summary of each bill enacted during a legislative session.

The Legislative Council Staff website has a lot of helpful information. The Economy and Budget page has information that can help inform a legislator about fiscal matters affecting proposed legislation. This includes economic forecasting, budget and tax information, school finance, and those oh-so-important fiscal notes, which estimate the fiscal impact of each bill. The website also has a Research and Publications page, which includes summaries of major legislation, issue briefs, and memoranda and resource books. Finally, the Legislative Resource Center page contains information about the legislative library and other places to find even more detailed information.

The General Assembly website has a wide variety of helpful information, including bill information, committee information, audit information, the law of Colorado, budget information, calendars and agendas for interim committees, and access to Blue Books for upcoming and past elections. The Blue Books provide summaries and arguments in favor of and against statewide initiatives and referred measures.

In addition, a legislator may also request research from the Council of State Governments, or CSG, the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, and the National Conference of State Legislatures, or NCSL. All of these entities are, by statute, joint governmental agencies of Colorado and of other states that cooperate through them. Each member of the Colorado General Assembly is automatically a member of CSG and NCSL and is eligible to join ALEC.

CSG, ALEC, and NCSL all have staff who are experts in various subject areas and are available by telephone and email to answer questions and assist legislators with research. In addition, each organization has a large variety of research materials, articles, surveys, and comparative information available through their websites. CSG and NCSL also have several archived webinars on a wide variety of topics that are available for view at no cost.

Finally, if a legislator is interested in legislation on a particular topic, each of these organizations may be able to provide examples. The NCSL website provides access to a 50-state bill tracker that you can use to find legislation introduced in recent legislative sessions in each of the 50 states. To access this information, you will need to log in as a legislator or as legislative staff.

Both the CSG and ALEC websites also provide access to examples of legislation. As mentioned above, NCSL has a bill tracking database, and CSG publishes compilations of draft legislation through its Shared State Legislation program. A committee of legislators and legislative staff from each state selects draft legislation to include in the publication with the goal of assisting each state in learning from the experiences in other states. Members of ALEC can access model legislation that is drafted and recommended by standing task forces on various subject areas. Each task force includes legislators from around the country and representatives of private sector partners who are members of ALEC.

In addition to having very helpful websites, CSG, ALEC, and NCSL each host meetings throughout the year. At these meetings, legislators and legislative staff from around the country meet to discuss policy areas and get information and presentations from experts in a variety of subject areas. These meetings also provide an excellent opportunity to network with legislators from other states and discuss the diverse approaches the states take in addressing similar issues. If you are ever interested in attending any of these meetings, see each organization’s website for more details.

As you can see, lots of resources are available to help legislators and other stakeholders set policies, draft legislation, and navigate the legislative process. And if you still need help—don’t we all at times?—OLLS, your other staff agencies, and many nongovernmental organizations stand ready to provide it.