Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of seven articles on statutory construction that LegiSource is reposting during the 2019 legislative interim. This article was originally posted July 31, 2014. We will post the third article in two weeks.

By Julie Pelegrin

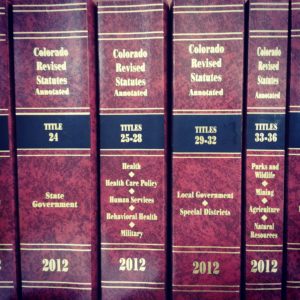

When debating legislation or reading statutes, a person will sometimes wonder what a specific word means as it’s used in the bill or the law. A word may be defined in several places and in different ways within the Colorado Revised Statutes – or it may not be defined at all. Following are some tips for figuring out whether the words in a bill or statute mean what you think they mean.

First, it’s important to know that there is a definitions section in the statutes that defines several words for purposes of the entire Colorado Revised Statutes. Section 2-4-401, C.R.S., states “The following definitions apply to every statute, unless the context otherwise requires:” and then defines several words, including:

First, it’s important to know that there is a definitions section in the statutes that defines several words for purposes of the entire Colorado Revised Statutes. Section 2-4-401, C.R.S., states “The following definitions apply to every statute, unless the context otherwise requires:” and then defines several words, including:

- Child, which includes a child by adoption;

- Immediate family member, which means a person who is related by blood, marriage, civil union, or adoption;

- Must, which means that a person is required to meet a condition for a consequence to apply;

- Person, which means any legal entity, including an individual, corporation, limited liability company, or government; and

- Shall, which means a person has a duty.

Most words, however, are not defined for the entire C.R.S. They are defined specifically for the title, article, part, or smaller subdivision of law in which they are used. The definition of “minor” is an interesting case in point. In one section of statute, “minor” means a person who is less than 22 years of age, and in another section, it means a person who is less than 18 years of age. The statute-wide definitions section – section 2-4-401 (6), C.R.S. – defines “minor” as a person who has not attained the age of 21 years. But also says that a statute that expressly states another age for majority will override this definition.

To discover whether and how a particular word is defined, you should look first at the statutory section in which the word is used to see whether the section includes any definitions. Usually, if the section includes definitions, the word “definitions” is included in the headnote (the type in bold at the beginning of the section). If the section doesn’t include definitions or if the word you’re looking for is not defined, you should look to the next larger grouping of statutes – either the beginning of the part or the beginning of the article in which the statutory section is located.

To discover whether and how a particular word is defined, you should look first at the statutory section in which the word is used to see whether the section includes any definitions. Usually, if the section includes definitions, the word “definitions” is included in the headnote (the type in bold at the beginning of the section). If the section doesn’t include definitions or if the word you’re looking for is not defined, you should look to the next larger grouping of statutes – either the beginning of the part or the beginning of the article in which the statutory section is located.

Note that the introductory portion of the definitions section specifies the portion of statute to which it applies, i.e., “As used in this part…” or “As used in this article…” or “As used in this title…” (etc.). Furthermore, the introductory portion to a definitions section or subsection almost always includes the words “unless the context otherwise requires.” This means, if the definition of a word conflicts with the context in which the word is used, the contextual meaning may override the written definition. The persons applying a statute, and, if necessary, a court, must decide which definition actually applies.

When reading a bill, remember that the definition of a word probably won’t appear within the bill unless the bill is specifically defining the word or changing the definition of the word. To understand how a word in a bill is defined, you may need to look up the definitions section in the existing law that applies to the section that the bill amends.

But, there will be many times when you will look for a definition in a bill or in the statutes and you won’t find one. Generally, a definition is included in a statute only if the word has more than one definition and it is important for clarity to define it specifically or if the word is a term of art. Also, a word may be defined to avoid repeated use of a long or awkward phrase. For example: the state board of public health and environment is usually defined as the “state board”.

But, there will be many times when you will look for a definition in a bill or in the statutes and you won’t find one. Generally, a definition is included in a statute only if the word has more than one definition and it is important for clarity to define it specifically or if the word is a term of art. Also, a word may be defined to avoid repeated use of a long or awkward phrase. For example: the state board of public health and environment is usually defined as the “state board”.

Generally, words used in a statute must be construed according to their commonly accepted meaning. So, if a court must interpret a statute, and the words used in the statute aren’t defined, the court will open the dictionary and interpret the statute by applying the standard definition of the word. If you’re reading a statute and wondering what an undefined word means, you should do the same!