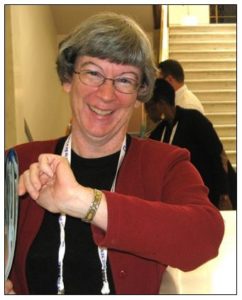

Sadly, the Office of Legislative Legal Services recently lost one of our own. Debbie Haskins passed away unexpectedly Saturday, October 7, from heart failure. Debbie served Colorado legislators for 34 years, practically her entire professional career. She took great pride and satisfaction in her service as nonpartisan legislative staff, helping literally hundreds of legislators achieve their legislative goals and serve the people of Colorado.

On October 1, 1983, Debbie began her career with the Office as a legislative attorney drafting bills. She developed great expertise in the areas of human services, criminal law, tort reform, and Medicaid. She was our go-to person for LGBT rights issues, state government organization issues, procedures for executive agency rules, and various family and children’s issues.

On October 1, 1983, Debbie began her career with the Office as a legislative attorney drafting bills. She developed great expertise in the areas of human services, criminal law, tort reform, and Medicaid. She was our go-to person for LGBT rights issues, state government organization issues, procedures for executive agency rules, and various family and children’s issues.

For a time during the ’90’s, Debbie was the supervising team leader for the group of attorneys and legislative editors drafting in the areas of criminal law, human services, public health, and civil law. And for the last seven years—in addition to drafting bills—she served as one of the office’s assistant directors, overseeing the rule review process, staffing the Committee on Legal Services, overseeing training for new employees and out-of-cycle training for new legislators, editing and maintaining the office’s drafting manual, and covering a myriad of other activities and details that helped keep our office running.

Debbie was a trusted colleague. She had been with the office the longest of anyone currently working here, and her memory, experience, wisdom, and bulging filing cabinets were invaluable assets that she shared generously. More than that, she was a friend. She was always available to talk with you about rules, about drafting issues you were running into, or about other challenges you were encountering. She had a quick smile and an easy, infectious laugh, and she enjoyed being helpful.

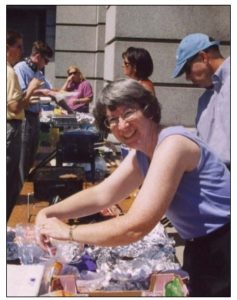

Debbie enjoyed being helpful outside the office as well. She was an active member of her church, serving on many committees and singing in the choir. And she was an indefatigable supporter of the Girl Scouts, serving as a troop leader, a chaperone on international trips, and a mentor for girls who were working on their Girl Scout Gold Award. For several years, she put in countless hours preparing for and helping host the annual Girl Scout Day at the Capitol.

And Debbie wasn’t just helpful in Colorado. She was helpful across the country. There are many legislative staff across the country who had the pleasure of working with Debbie through her active involvement with the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). In 2009-10, Debbie served as vice chair and in 2010-11 she served as chair of the Legal Services Staff Section (now known as the Research, Legal, Editorial, and Committee Staff (RELACS) association), an NCSL-sponsored organization of legislative staff throughout the United States. In addition, she served on several RELACS association committees, including serving several years on the  program committee, helping to assure that RELACS provided the highest quality professional development possible at national NCSL meetings.

program committee, helping to assure that RELACS provided the highest quality professional development possible at national NCSL meetings.

Debbie was also well known for teaching many of those professional development programs, both in-person at national meetings and through webinars. Most recently, she participated on a panel discussing The Drafting Manual as a Tool for Statutory Interpretation presented at the RELACS professional development seminar in September. While perhaps not the most exciting topic to non-legislative staffers, our drafting manual was very important to Debbie since she had diligently edited and updated it for decades.

For her work with NCSL, Debbie received the Legal Services Staff Section Chair Award in 2011. And in 2012 she received the Legislative Staff Achievement Award for her long and distinguished career with the Colorado General Assembly.

Clearly, Debbie was a valued, respected, and beloved member of the Capitol Community, well known and greatly appreciated by legislators, lobbyists, and staff from all of the legislative staff agencies. We will deeply miss her positive presence in the months and years to come, but she leaves to us a model of hard work and dedication to nonpartisan service that we will do well to follow.