by Julie Pelegrin

Newly elected legislators are often (pleasantly) surprised to find that they do not have to write their own bills. The Office of Legislative Legal Services – a nonpartisan legislative staff agency – provides expert legislative drafting services to help legislators put their policy ideas into statutory language. But this was not always the case. For over 90 years, Colorado’s legislation was written by employees of the executive branch.

From the first Legislative Assembly of the Colorado Territory in 1861 until 1917, it’s not clear who was writing the legislation. There is no mention of bill drafting services in the statutes or anywhere else that we can find. Presumably, every legislator wrote his or her own bills, although some may have sought help from private attorneys or the Attorney General. The first mention we find of a bill drafting office is in the 1917-18 biennial report of Colorado Attorney General (AG) Leslie E. Hubbard. He reports that he formed a division within the Attorney General’s office to assist legislators in writing bills. His motivation: To avoid the introduction of bills with “patent inaccuracies, conflicts and constitutional objections” and so reduce the amount of litigation against the state.

It appears this informal division of the AG’s office continued to operate until 1927. That year, the General Assembly officially created a legislative reference office (LRO) within the Attorney General’s office with the passage of S.B. No. 200. The LRO consisted of one attorney who served as director of the office and at least one stenographer. The Attorney General appointed the LRO director, with the consent of the Governor. S.B. No. 200 also authorized the Supreme Court Librarian to assign library employees to work with the LRO during the legislative session.

It appears this informal division of the AG’s office continued to operate until 1927. That year, the General Assembly officially created a legislative reference office (LRO) within the Attorney General’s office with the passage of S.B. No. 200. The LRO consisted of one attorney who served as director of the office and at least one stenographer. The Attorney General appointed the LRO director, with the consent of the Governor. S.B. No. 200 also authorized the Supreme Court Librarian to assign library employees to work with the LRO during the legislative session.

From the beginning, the employees of the LRO were nonpartisan – appointed without reference to party affiliation, solely on the ground of fitness. The director of the LRO had to be an attorney licensed to practice law for at least five years before appointment. And all bill requests were confidential; neither the director nor any employee of the LRO could reveal to anyone outside the office the contents or nature of a bill request without the requesting legislator’s consent. Also, the director and the LRO employees were prohibited from lobbying in favor of or against any type of legislation.

The LRO had several duties including: Maintaining bill files and information relating to bills; accumulating data and statistics concerning the practical operation of Colorado’s statutes and those of other states; studying the statutes to find ways to reduce the number and bulk of the statutes; and working with the legislative reference bureaus in other states.

Most importantly, at a legislator’s or the Governor’s request, the LRO was required to draft bills, resolutions, and amendments; advise the legislature or the Governor as to the constitutionality or probable effect of proposed legislation; prepare summaries of existing laws and compilations of laws in other states; and research proposed legislation.

Although employees of the executive branch were drafting legislation for the legislative branch, the separation-of-powers implications did not seem to cause any concern – at least not until 1968. That year, Senator Bill Armstrong and Representative Star Burton Caywood introduced and passed S.B. 1, concerning the administrative reorganization of state government. This was a massive bill, the product of at least two years of interim committee meetings and planning. The act significantly restructured state government, reducing the sprawling mass of executive branch agencies and offices to just 17 state executive departments.

S.B. 1 also moved the LRO out of the Attorney General’s office and into the legislative department, renaming it the Legislative Drafting Office (LDO). And the bill created the Legislative Drafting Committee, a bipartisan committee consisting of the three members of leadership in each house and one additional minority party member appointed from each house.

The new LDO had a director, appointed by the legislative drafting committee without regard to party affiliation, who had to be an attorney. The director could appoint additional attorneys and clerical personnel as necessary to staff the office. The duties of the new LDO were essentially the same as the old LRO, except the attorneys in the LDO could no longer advise the Governor as to whether to sign a bill.

In 1969, the General Assembly passed S.B. 396, which, among other things, renamed the legislative drafting committee the Committee on Legal Services and changed the membership to consist of eight legislators and the Attorney General – but it remained a bipartisan committee. The General Assembly removed the Attorney General from the committee in 1973 and expanded the membership to 10 legislators in 1985.

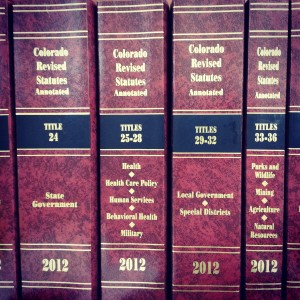

Finally, in 1988, the General Assembly passed House Bill 1329, which combined the LDO and the Office of the Revisor of Statutes into what we now know as the Office of Legislative Legal Services (OLLS). The duties of the OLLS did not change significantly from those exercised by the LDO, but, with the addition of the Office of the Revisor of Statutes, the OLLS is also responsible for revising, codifying, and publishing the statutes.

Several things about the OLLS have not changed as it has evolved from the executive branch into the legislative branch. Bill and amendment requests and communications between OLLS staff and legislators are all still confidential. The OLLS is still nonpartisan and is still charged with providing legal services. And, finally, the mission of the OLLS continues to be providing “the best technical advice and information … available to the General Assembly, agencies of state government, and the people of this state.”