by Patti Dahlberg

This week LegiSource continues its series on the statutory committees that oversee the legislative staff agencies. So far the series has looked at the Legislative Council and the Audit Committee. This week, we review the history and duties of the Committee on Legal Services.

The Committee on Legal Services is one of four joint “standing” or year-round legislative committees of the Colorado General Assembly charged with the oversight of a legislative staff agency. The Committee on Legal Services has oversight responsibilities regarding review of executive branch agency rules, legislation review, publication of the Colorado Revised Statutes, and the general operations of the Office of Legislative Legal Services. In addition, the Committee also introduces several key statutorily required bills related to its oversight responsibilities and key responsibilities regarding state government.

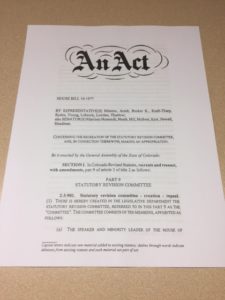

The Office of Legislative Legal Services (OLLS) and the Committee on Legal Services (Committee) were created in 1968 in Senate Bill 1 – an act “Concerning the Administrative Reorganization of State Government.” Section 178 of the bill established a Legislative Drafting Office as part of the legislative department “in order to promote the careful consideration of bills before their presentation to the general assembly by making the best technical advice and information readily available to legislators . . .”. Prior to this date, employees of the attorney general’s office in the executive branch drafted the bills. Although renamed, repealed, and reenacted, the OLLS and its purpose remains the same. [Section 2-3-501, Colorado Revised Statutes (C.R.S.)]

The General Assembly created the Committee, originally called the Legislative Drafting Committee, to supervise and direct the operation of the newly created drafting office. Again, there was a new name, some new wording, but still the same purpose. See also, “Legislature Passes the Laws – But Executive Branch Used to Write Them” (November 3, 2016) and “Revisor of Statutes Ensures Access to Colorado’s Laws” (November 17, 2016).

Committee basics. Pursuant to section 2-3-502, C.R.S., the Committee consists of 10 members of the Colorado General Assembly. Committee  members include the chairs of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, or their respective designees, four members appointed from the House of Representatives, and four members appointed from the Senate. There must be two members appointed from each major political party, and at least one member from each party in each chamber must be an attorney, if there is an attorney in that party and chamber. The Speaker of the House, the President of the Senate, and the minority leaders of each chamber, appoint the Committee members from their respective parties and chambers, subject to the approval of a majority of the members in each respective chamber, within the first 10 days after a first regular session convenes. The Committee selects its own chair and vice-chair. The Committee may meet as often as necessary, but is required to meet at least twice in each calendar year.

members include the chairs of the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, or their respective designees, four members appointed from the House of Representatives, and four members appointed from the Senate. There must be two members appointed from each major political party, and at least one member from each party in each chamber must be an attorney, if there is an attorney in that party and chamber. The Speaker of the House, the President of the Senate, and the minority leaders of each chamber, appoint the Committee members from their respective parties and chambers, subject to the approval of a majority of the members in each respective chamber, within the first 10 days after a first regular session convenes. The Committee selects its own chair and vice-chair. The Committee may meet as often as necessary, but is required to meet at least twice in each calendar year.

The Committee has the following statutory duties:

- Supervision and direction of Office of Legislative Legal Services. Pursuant to section 2-3-502 (1), C.R.S., the Committee is to “supervise and direct operations of the Office of Legislative Legal Services.” One of six legislative staff agencies, the OLLS is the nonpartisan, in-house counsel for the Colorado General Assembly and drafts legislation and produces the statutes in addition to its other statutory duties. In its supervisory role, the Committee recommends to the Executive Committee the appointment of a director for the OLLS and approves the OLLS’s annual budget.

- Overseeing the review of executive branch agency rules by the OLLS staff. Under section 24-4-103 (8)(c)(I), C.R.S., all rules adopted or amended by state agencies during a one-year period that begins November 1 and continues through the following October 31 automatically expire the following May 15 unless the General Assembly passes a specific bill to postpone this expiration date. A “rule” is a formal written

statement of law that a state agency adopts to carry out statutory policies and administer programs. The General Assembly authorizes an agency to make rules and then reviews and, if necessary, invalidates any rules that are not within the agency’s statutory authority or that conflict with state law. The OLLS staff review each rule and bring any rule issue they cannot resolve with an agency to the Committee for a rule hearing. At the hearing, the Committee decides whether to recommend expiration or extension of the rule. The Committee annually sponsors the Rule Review Bill that contains the Committee’s rule recommendations. See also, “The Legislature’s Role in the Review of Administrative Rules” (September 1, 2011) and “Legislative Oversight of State Agency Rule-making” (September 4, 2014).

statement of law that a state agency adopts to carry out statutory policies and administer programs. The General Assembly authorizes an agency to make rules and then reviews and, if necessary, invalidates any rules that are not within the agency’s statutory authority or that conflict with state law. The OLLS staff review each rule and bring any rule issue they cannot resolve with an agency to the Committee for a rule hearing. At the hearing, the Committee decides whether to recommend expiration or extension of the rule. The Committee annually sponsors the Rule Review Bill that contains the Committee’s rule recommendations. See also, “The Legislature’s Role in the Review of Administrative Rules” (September 1, 2011) and “Legislative Oversight of State Agency Rule-making” (September 4, 2014). - Overseeing Legislation Review. Pursuant to section 24-4-108 (7), C.R.S., the Committee has established procedures for the annual review of newly adopted legislation and its impact on agency rules. After the legislative session ends each year, the OLLS staff identifies legislation that affects rules or requires or permits agencies to adopt rules. The OLLS staff sends a letter to each principal department listing bills that affect that department’s rule-making authority. In addition, the OLLS staff is directed by section 24-4-103 (8)(e), C.R.S., to notify bill sponsors, co-sponsors, and committees of reference when the OLLS receives rules that implement newly enacted legislation. The OLLS staff sends these notices by e-mail.

- Litigation involving the General Assembly or its members. Pursuant to section 2-3-1001, C.R.S., the Committee may retain legal counsel to represent the General Assembly as a whole, the House, the Senate, a legislative committee, an individual member of the General Assembly, or a legislative staff agency or employee of the General Assembly in all actions and legal proceedings that arise from the performance of legislative duties.

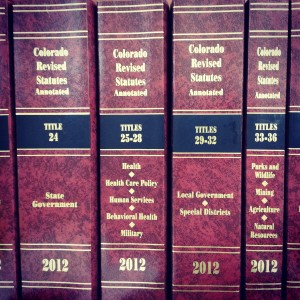

- Supervising the preparation, printing, and distribution of the Colorado Revised Statutes. The Revisor of Statutes must perform numerous duties related to revising and compiling the Colorado Revised Statutes and Session Laws, all under the supervision and direction of the Committee (sections 2-3-701 to 2-3-705, C.R.S.). Section 2-5-104, C.R.S., authorizes the Committee to introduce one or more Revisor’s Bills each year, which may address “amendments or repeals of obsolete, inoperative, imperfect, obscure, or doubtful laws as the Revisor of Statutes considers necessary to improve the clarity and certainty of the statutes.” The Committee also sponsors an annual bill to enact the legislation adopted at the previous legislative session as the statutory law of Colorado. The Committee must contract through a bidding process for the printing, binding, and packaging of softbound volumes of the Colorado Revised Statutes and Session Laws. In addition, as part of its publication responsibilities, the Committee is overseeing the implementation of the “Uniform Electronic Legal Material Act” (section 24-71.5-101, C.R.S., et. seq.) as it relates to the electronic publication of the statutes and other legal materials.