A Holiday Message

HAPPY HOLIDAYS FROM THE OLLS!

HAPPY HOLIDAYS FROM THE OLLS!

by Nate Carr Each year a small, one-page bill works its way through the legislative process. It’s typically at the front of the legislative bill line, so to speak, and […]

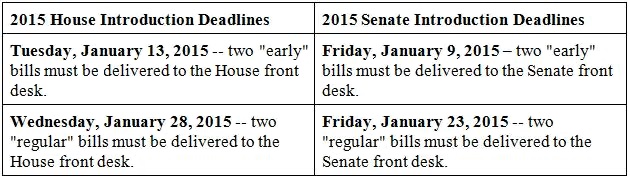

by Patti Dahlberg According to Joint Rule 24(b)(1)(A), each session a legislator is allowed five bill requests. These five requests are in addition to any appropriation, committee-approved, or sunset bills […]

by Patti Dahlberg “Legislative oversight” generally refers to a legislature’s review and evaluation of selected activities, services, and operations and the general performance of the executive branch of government. The […]

By Jennifer Berman There are numerous demands on Colorado’s water supply. Colorado has a population of 5 million people, and some forecasts project that number will almost double by 2050. […]