by Julie Pelegrin

Since 1921, the law has required elementary, junior, and high school teachers and college and university professors to take what’s called a “loyalty oath” affirming their loyalty to both the country and the state. The wording of the oath has changed over the years and been challenged a couple of times in court, but it’s still on the books as a requirement for licensed teachers or for employment as faculty in a public postsecondary institution.

Oaths to uphold the constitution are common for elected officials. Since 1876, the Colorado Constitution has required every legislator and every other elected officer to take an oath to uphold the U.S. and Colorado constitutions and to “faithfully perform the duties of his office according to the best of his ability.”

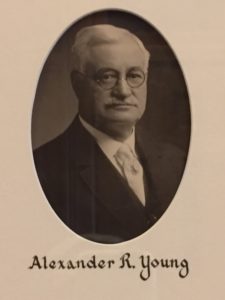

But in 1921, the General Assembly passed S.B. No. 123, by Senator Alexander R. Young and Representatives Mabel Ruth Baker and Charles C. Sackmann, entitled “An act to provide for an oath or affirmation of allegiance to be taken by all persons who are teaching or who may hereafter be employed to teach in public, private or parochial schools or other institutions of learning in the state of Colorado.”

But in 1921, the General Assembly passed S.B. No. 123, by Senator Alexander R. Young and Representatives Mabel Ruth Baker and Charles C. Sackmann, entitled “An act to provide for an oath or affirmation of allegiance to be taken by all persons who are teaching or who may hereafter be employed to teach in public, private or parochial schools or other institutions of learning in the state of Colorado.”

Why then? And why teachers?

Think back to your American and world history classes. The United States helped broker the armistice that ended World War I—the “war to end all wars”— in 1918. Also, the Russian Revolution, which eventually resulted in the Bolsheviks taking over the government and installing the Communist regime, occurred in 1917.

According to the Fort Collins Courier, in an editorial titled “Teachers Must Swear Loyalty,” published August 23, 1919, during the war, “a number of cases came to light of teachers who openly or by clever insinuation tried to undermine the children’s belief in their country, its cause and in the fundamental ideals of honest democracy. Although such cases were not common, they were numerous enough to create a real menace.” The Steamboat Pilot (“Gossip of State Capital” Feb. 16, 1921), also noted that “[d]uring the World war many disloyal teachers were uncovered, especially in Denver.”

The Courier was in favor of a new law passed by Ohio that required all teachers in public, private, and parochial schools to take an oath of allegiance to the United States, at least for elementary, middle, and high schools. However, with regard to colleges and universities, the Courier thought “application of the law to be of dubious wisdom.” They didn’t want the law to cut off the benefits of having exchange professors who explained the viewpoints of their respective countries. They recognized that lectures by professors visiting from other countries could “bring about a pleasanter relationship based on mutual understanding.” But they also noted that the law “would of course keep out the propagandist and the man with dangerous alien doctrines.”

Support for the bill was not unanimous across the state, however. The Leadville Herald Democrat opposed the bill in February of 1921, noting that the governor of Montana had vetoed a similar bill and urging Governor Shoup of Colorado to do the same once the bill landed on his desk. The Herald Democrat noted that requiring a teacher to declare his or her belief in the “‘American form’ of government” was supposed to “minister to a sort of super-patriotic sentiment” and keep “dangerous radicals” from putting the wrong ideas into students’ heads. But the effect of this requirement is actually to put “powerful weapons in the hands of the political heresy hunters, a phrase that [the Montana] governor uses….” It concluded with the remark: “The state needs good teachers, not automatons.” (Leadville Herald Democrat, “A False Political Test” February 6, 1921.)

Despite the Herald Democrat‘s misgivings, the bill sailed through the legislature. It was introduced in the Senate on January 13 and passed on third reading in the House on February 7 without amendment. On February 15, 1921, Governor Shoup signed it into law.

In June, the Herald Democrat was still railing against it. “The truth is that these and kindred measures are after-war reactions, based on the theory that the country is full of radicalism, revolution and strange doctrine.” The article notes that in the most recent election, “radical parties were almost wiped off the slate” and argues that the real threat to “the structure of Americanism” is “the introduction of too much of the Prussian system of state worship…” (Leadville Herald Democrat, “The Oath of a Teacher” June 4, 1921.)

That fall, the American Legion held its national convention in Kansas City from October 31 to November 2. The Routt County Sentinel reported the convention highlights, including a list of items included in the Legion’s platform. Among other issues, the American Legion included these planks:

Education in citizenship is the keynote of Americanism.

That American history and civil government be taught more thoroughly in our public schools.

Favoring state laws requiring every teacher to take an oath of allegiance to uphold the constitution and the conciliation of certificates of those teachers found disloyal to the American government.

(Routt County Sentinel, “High Lights on Legion’s National Convention” Nov. 25, 1921.)

Based on the newspaper coverage, we can deduce that the teacher loyalty oath statute arose out of the support for “Americanism” that was engendered by World War I and the threat, real or perceived, of anti-American, anarchist, and possibly Communist elements in society. So starting in the fall of 1921 and each year thereafter, all new teachers and professors were required to solemnly swear or affirm:

[T]hat I will support the constitution of the State of Colorado and of the United States of America and the laws of the State of Colorado and of the United States, and will teach, by precept and example, respect for the flags of the United States and of the State of Colorado, reverence for law and order and undivided allegiance to the government of one country, the United States of America.

Until 1969, that is. That year, the General Assembly amended the oath to its current form:

I solemnly (swear) (affirm) that I will uphold the constitution of the United States and the constitution of the state of Colorado, and I will faithfully perform the duties of the position upon which I am about to enter.

Why the change? And why then?

We’ll talk about that next week. Hint: The answers lie with the judicial branch.