By Jessica Wigent

This week LegiSource publishes its final installment in the series on statutory committees that oversee the legislative staff agencies. The series so far has addressed the history and duties of the Legislative Council, the Audit Committee, and the Committee on Legal Services. We close the series by looking at the Joint Budget Committee.

The evolution of what would become the Joint Budget Committee, or JBC, began in 1955, when then-Representative Palmer Burch, a member of the joint subcommittee on Appropriations, took the reins of the budget from the governor to the legislature. This was the first, as John Straayer describes in his book The Colorado General Assembly, “legislative effort to develop budgetary expertise independent of …  the executive branch.” It turned out well: The budget passed that year, with zero (!) amendments, and was signed into law. The next year, the General Assembly, impressed with the subcommittee’s efforts, approved an appropriation to hire outside staff to work specifically on the budget. And finally, in 1959, the JBC was officially created.

the executive branch.” It turned out well: The budget passed that year, with zero (!) amendments, and was signed into law. The next year, the General Assembly, impressed with the subcommittee’s efforts, approved an appropriation to hire outside staff to work specifically on the budget. And finally, in 1959, the JBC was officially created.

With great power comes great responsibility

You won’t find the word “budget” in the constitution Colorado adopted in 1876, but passing the state’s budget is possibly the most important duty of the General Assembly. The budget is a reflection of the state’s priorities—legislators have to balance it, and they have to pass it. And for that to happen, they depend on the JBC.

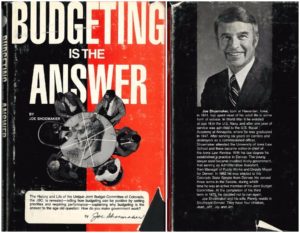

As Bob Ewegen, a statehouse reporter for the Denver Post in the 1970s, wrote in the introduction to Budgeting is the Answer, there are no monuments to budget committees, because “the complex and  intricate mechanisms which govern society may engage men’s minds–but seldom stir their souls.” And yet the JBC’s invention and development was and has been not only innovative but integral to the success of the state.

intricate mechanisms which govern society may engage men’s minds–but seldom stir their souls.” And yet the JBC’s invention and development was and has been not only innovative but integral to the success of the state.

Considered by many to be the most powerful committee in the General Assembly, the JBC is also the smallest.

Former Senator Joe Shoemaker, the author of Budgeting, and a member of the JBC for 12 years, described why the size of the committee, just six members—three from the House and three from the Senate—is important:

“Six was a good number to provide team spirit and camaraderie that helped us face the pressure and criticism bound to come with good budget making.”

As described by the Senator, the JBC is a David-sized committee with a Goliath-sized task. The six members include the chairs of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, a logical choice as the work of those committees and the JBC is inextricably connected. The former deals with the funding requirements of newly introduced legislation and the latter the ongoing fiscal needs of the state. The other four JBC members—one majority and one minority member from each house—are appointed by their respective majority or minority leader. In the Senate (see Senate Rule 21), the appointees are first elected by their respective party caucus.

As described by the Senator, the JBC is a David-sized committee with a Goliath-sized task. The six members include the chairs of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, a logical choice as the work of those committees and the JBC is inextricably connected. The former deals with the funding requirements of newly introduced legislation and the latter the ongoing fiscal needs of the state. The other four JBC members—one majority and one minority member from each house—are appointed by their respective majority or minority leader. In the Senate (see Senate Rule 21), the appointees are first elected by their respective party caucus.

A condensed version of the members’ very busy terms includes: Public hearings of budget requests in the fall before the legislative session begins; writing the budget in more public hearings, line by line, for each department and institution, each line of which requires a vote; sending the bill to the appropriations committees, the party caucuses, and finally the floors of the House and Senate, where it’s 99.9% likely to be amended, which means after its passage in both houses, the JBC must meet as the conference committee to navigate the changes made to the budget in each house and how to patch it up.

More than just number$

For more than half a century, the various members of the JBC have been, according to Shoemaker, “pioneering in the complex, often dreadfully dry, but intensely important saga of governmental budgeting.”

Among their innovations and accomplishments—the name of the budget itself: The “Long Bill”, a not-wildly-creative-yet-accurate description for a document hundreds of pages long that when combined with the previous years’ budgets reflects a comprehensive history of the priorities of the state. If you’ve ever contemplated its many pages, you’ll notice that it contains line items, not just lists of numbers, and that headnotes and footnotes spell out the legislative intent of the funds appropriated. These notes are the answers to the question JBC members ask department heads and agency administrators: “What’s the money for?”

Members of the JBC also developed the idea of budgeting for an FTE, or a full-time-equivalent position, as opposed to appropriating money in the abstract for new hires, as well as the performance budget, the first of which was presented in 1974, which allows the JBC to take into account a department’s or  institution’s performance goals and up-to-date reporting on their budgeted and actual expenditures.

institution’s performance goals and up-to-date reporting on their budgeted and actual expenditures.

The JBC’s innovations have proven that, for a budget to serve the people, it must be more than a collection of numbers and dollar signs.

With the help of their small, but talented staff, whose dedication the Senator called “contagious” (in a good way!), the members of the JBC are statutorily required to:

- Study the management, operations, programs, and fiscal needs of state government;

- Hold hearings to review budget requests of each state agency and institution;

- Review performance plans and performance evaluations of departments, considering each department’s responsibilities, goals and objectives, and, when appropriate, prioritize requests for new funding that are intended to enhance productivity, improve efficiency, reduce costs, and eliminate waste;

- Estimate the amount of revenue expected from existing and proposed taxes;

- Study, “from time to time,” the state’s financial condition, fiscal organization, and budgeting; and accounting, reporting, personnel, and purchasing procedures; and

- Work with the capital development committee concerning new methods of financing the state’s ongoing capital construction, capital renewal, and controlled maintenance needs.

And while the hatchet that once hung behind the JBC members as they questioned administrators, and which more recently was mounted to a piece of wood in the middle of the dais in the Committee’s room, may have been retired, Senator Shoemaker seemed to think it was an imperfect metaphor anyway. He described the work of the JBC as “not the result of thoughtless chopping … [but of] a carefully considered form of fiscal surgery.”

which more recently was mounted to a piece of wood in the middle of the dais in the Committee’s room, may have been retired, Senator Shoemaker seemed to think it was an imperfect metaphor anyway. He described the work of the JBC as “not the result of thoughtless chopping … [but of] a carefully considered form of fiscal surgery.”

Whichever metaphor suits your view of the Joint Budget Committee, you’re in luck—the Committee will begin holding a series of (many) meetings on Monday, November 13, 2017, to hear the governor’s budget request and the briefings from the state’s agencies, departments, and institutions.

An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of Representative Palmer Burch. We regret and have corrected the error.